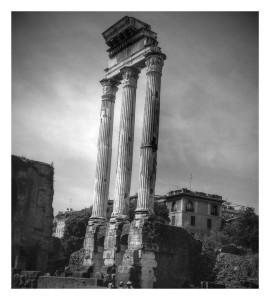

dying ash tree, Fairfax County, Virginia; photo by F.T. Campbell

According to Aukema et al. 2010 (see references at the end of this blog), by the first decade of the 21st Century, the number of non-native insects and pathogens damaging our forests had risen to at least 475. Sixty-two of the insects, and all of the 17 pathogens, were judged to have “high impact”, with both economic and ecological ramifications. More than 181 exotic insects that feed on woody plants are established in Canada (USDA APHIS 2009). Especially hard-hit is the eastern deciduous broadleaf forest — there is an exotic pest threat to nearly every dominant tree species in this ecosystem type.

The situation is actually worse than this article and others based on it depict. Aukema et al. 2010 did not include several highly damaging forest pests that are native to regions of North America (e.g., goldspotted oak borer, thousand cankers disease); nor did they include pests on U.S. islands, such as `ohi`a rust and Erythrina gall wasp in Hawai`i. Aukema et al. 2010 also did not include pests that attack palms or cycads – which are significant components of some ecosystems on the continent as well as on America’s tropical islands. Finally, some invaders have come to our attention since the database on which these authors relied was compiled, e.g., polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers and the rapid ohia death pathogen. (For a list of pests detected since 2003, see page 7 of Fading Forests III, available here; this list was compiled in 2014, so it does not include the most recently detected pests, such as rapid ohia death. For descriptions of most invaders discussed in this blog, go here.)

Of course, more important than numbers are impacts. Lovett et al. 2016 provide a summary of those impacts … but let’s get specific. Note that some of these species occupy wide ranges; it is not only the narrow endemics that are under threat.

- Several tree species are severely depleted throughout their ranges: American chestnut, Fraser fir, Port-Orford cedar, butternut, Carolina hemlock, redbay and swamp bay, cycads on Guam

- Other species or genera are already severely reduced in significant portions of their ranges and the causal agents are spreading to the remaining sanctuaries: whitebark pine.

- In some cases, the causal agent has not yet spread, but threatens to: `ohi`a.

- Some tree or shrub taxa are under severe attack across much of their ranges: ashes, eastern hemlock, American beech, dogwoods, tanoak, viburnums …

Many of America’s 300 species of oak face a variety of threats:

- in the East, European gypsy moth, oak wilt, and – in some areas – winter moth;

- in the South, oak wilt and Diplodia;

- on the West coast, sudden oak death, goldspotted oak borer, the polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers, Diplodia, and foamy bark canker.

(For more about threats to oaks, see my blog from last April.)

Other threats are – so far – confined to relatively small areas, but they could break out. These include the multi-host insects Asian longhorned beetle; polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers; and spotted lanternfly. Tree genera containing species at risk to one or more of these insects include maple, elm, willow, birch, sycamore, cottonwood and poplar, sweet gum, oak. Only ALB and the lanternfly currently are the focus of federal and state programs aimed at eradication or containment. The widespread invasive tree, Ailanthus or tree of heaven, could support spread of at least the polyphagous shot hole borer and spotted lanternfly.

Of course, additional pests are likely to be introduced (or detected) in the future. Known threats include the various Asian subspecies of gypsy moth and ash dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus – previously called Chalara fraxinea). If history is any guide, we are likely to be surprised by a highly destructive invader that we have either never heard of or dismissed based on its behavior elsewhere. See my earlier blogs for discussions of what should be done to reduce the introduction risk associated with wood packaging and imports of living plants.

What Should We Do?

2017 brings a new Administration and a new Congress. At a minimum, we need to educate all these decision-makers about both the high costs imposed by tree-killing insects and pathogens and effective strategies to minimize those costs. How will our concerns be received? We don’t know yet.

We might have opportunities arising from the skeptical attitude toward trade voiced during the campaign. Will newly elected or appointed agency and Congressional staffers be open to re-considering the plant health threats associated with international trade? On the other hand, will mainstream agriculture’s traditional strong support for exports continue to overwhelm calls to strengthen phytosanitary measures? Even if our message about risks associated with trade gains a hearing, will officials be willing to consider more rigorous regulations? Or higher funding levels for agencies responsible for plant pest prevention and response?

I hope you will join the Center for Invasive Species Prevention and others in coordinated efforts to take these messages to the next Secretary of Agriculture (who has not yet been named!) and key members of the Senate and House of Representatives. Opportunities in the Congress include Senate confirmation of the new Secretary and the three Under Secretaries that oversee APHIS, USFS, and ARS; annual appropriations bills; and early consideration of possible amendments to the Farm Bill (which is due for renewal in 2019).

See my post from a week ago for more suggestions for how Congress could improve U.S. invasive species management programs.

Expect to hear from me often in the coming year!

SOURCES

Aukema, J.E., D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle, A.M. Liebhold, K. Britton, & S.J. Frankel. 2010. Historical Accumulation of Nonindigenous Forest Pests in the Continental United States. Bioscience. December 2010 / Vol. 60 No. 11

Lovett, G.M., M. Weiss, A.M. Liebhold, T.P. Holmes, B. Leung, K.F. Lambert, D.A. Orwig , F.T. Campbell, J. Rosenthal, D.G. McCullough, R. Wildova, M.P. Ayres, C.D. Canham, D.R. Foster, S.L. LaDeau, and T. Weldy. 2016. Nonnative forest insects and pathogens in the United States: Impacts and policy options. Ecological Applications, 0(0), 2016, pp. 1–19. DOI 10.1890/15-1176.1

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. 2009. Risk analysis for the movement of SWPM (WPM) from Canada into the US.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.