NOW is the time to advocate inclusion of important proposals in the 2018 Farm Bill. It is currently under consideration by the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate. If we miss this round of Farm Bill legislation, there won’t be another opportunity until 2023. Urge your Senators and Representative to support creation of the two grant-based funds described below.

What’s the issue?

We know that about 500 species of non-native insects and pathogens that attack native trees and shrubs are established in the United States. The number in Canada is 180 – there is considerable overlap.

Protecting the trees and their ecosystem services requires development and deployment of a set of tools aimed at either reducing the pests’ virulence or strengthening the tree hosts’ resistance or tolerance. Such strategies include biological control targetting the insect or pathogen and breeding trees resistant to the pest. Developing and employing these tools require sustained effort over years.

Unfortunately, the programs now charged with responding to introduced forest pests are only a ragged patchwork of university, state, and federal efforts. They provide neither the appropriate range of expertise nor continuity. (For a more thorough discussion of the resources needed to restore tree species badly depleted by non-native pests, read Chapter 6 of Fading Forests III, posted here.)

CISP-backed Amendments

In order to begin filling the gaps, the Center for Invasive Species has proposed forest-related legislation for the Farm Bill currently being considered by Congress.

We propose creation of two new funds, each to provide grants to support tree-protection and restoration projects. We find that the expertise and facilities needed to plant and maintain young trees in the forest differ enough from those needed to research and test biological approaches to pest management and tree improvement that each deserves its own support.

Our first proposal would create a grant program managed by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) to provide long-term funding for research to restore tree species severely damaged by alien pests. The focus of the research would be on:

- Biocontrol of pests threatening native tree species;

- Exploration of genetic manipulation of the pests;

- Enhancement of host- resistance mechanisms for individual tree species;

- Development of other strategies for restoration; and

- Development and dissemination of tools and information based on the research.

Entities eligible for funding under our proposal would include:

- Agencies of the U.S. government;

- State cooperative institutions;

- A university or college with a college of agriculture or wildlife and fisheries; and

- Non-profit entities recognized under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Our second proposal would provide long-term funding to support research into and deployment of strategies for restoring pest-decimated tree species in the forest. The source of funds would be the McIntire-Stennis program. The eligible institutions would be similar: schools of forestry; land grant universities; state agricultural and forestry experimental stations; and non-profit non-governmental organizations. Projects would integrate the following components into a forest restoration strategy:

- Collection and conservation of native tree genetic material;

- Production of propagules of native trees in numbers large enough for landscape scale restoration;

- Site preparation of former of native tree habitat;

- Planting of native tree seedlings; and

- Post-planting maintenance of native trees.

In addition, competitive grants issued by this second fund would be awarded based on the degree to which the grant application addresses the following criteria:

- Risk posed to the forests of that state by non-native pests, as measured by such factors as the number of such pests present in the state;

- The proportion of the state’s forest composed of species vulnerable to non-native pests present in the United States; and

- The pests’ rate of spread via natural or human-assisted means.

(To request the texts of the proposed amendments, use the “contact us” button.)

A Growing Chorus Sees the Same Need

A growing chorus of scientists is calling for long-term funding for forest restoration programs based partly on recent scientific breakthroughs. So this year’s Farm Bill provides a key opportunity for initiating such programs.

The NIFA Letter

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture asks scientists each year to suggest their highest priorities for the agency’s research, extension, or education efforts. In December, twenty-eight scientists replied by calling for setting up a special “division” within NIFA to fund breeding of pest-resistant tree species and associated extension.

The lead authors are Pierluigi (Enrico) Bonello, Ohio State University, and Caterina Villari, University of Georgia. The 26 co-signers are scientists from 12 important research universities, along with the U.S. Forest Service (the Universities of Georgia, California (Berkeley), Florida, Kentucky, Minnesota, and West Virginia; Auburn University; Michigan Technological University; North Carolina State University; Oregon State University; Purdue University; the State University of New York).

The scientists note that recent scientific advances have created a new ability to exploit genetic resistance found in the tree species’ natural populations. They assert that developing and deploying host resistance promises to improve the efficacy of various control strategies – including biocontrol – and provides a foundation for restoring forest health in the face of ever-more non-native forest pests.

The scientists’ proposal differs from CISP’s in calling for establishment of research laboratories and field study sites at several locations in the country. These would be permanently funded to conduct screening and progeny trials, and adequately staffed with permanent cadres of forest tree geneticists and breeders who would collaborate closely with staff and university pathologists and entomologists. The apparent model is the USDA Forest Service’ Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Oregon. Dorena has had notable success with breeding Port-Orford cedar and several white pine species that are tolerant of the pathogens that threaten them.

In contrast, the CISP proposal relies largely on the chestnut model, which relies more on non-governmental organizations and wide-ranging collaboration. Our overall goal is similar, though: to provide stable funding for the decades-long programs needed to restore forest tree species.

American Chestnut Foundation chestnut growing in Northern Virginia

American Chestnut Foundation chestnut growing in Northern Virginia

Why do we advocate grant programs instead of establishment of permanent facilities? We thought that Congress would be more likely to accept a smaller and cheaper set of grant programs in the beginning. Once the value of the long-term strategies is demonstrated more widely, supporters would have greater success in lobbying for creation of the permanent facilities.

Among the new technologies that would seem to justify the scientists’ assertion that success in breeding now appears to be more likely is the use of FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy and associated analysis of tree chemicals to identify individual trees within natural populations that have an apparent ability to tolerate disease-causing organisms. The leading scientist on the NIFA letter, Enrico Bonello, has used the technique to identify coast live oaks resistant to Phytopthora ramorum (the causal agent of sudden oak death. He is now testing whether the technique can identify Port-Orford cedar trees tolerant of the root-rot fungus Phytophthora lateralis and whitebark pines resistant to white pine blister rust.

I blogged about Enrico’s work on ash resistance to EAB here.) You can learn more about Enrico’s interesting work here.

The NAS Study

Meanwhile, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has launched a study on The Potential for Biotechnology to Address Forest Health. By the end of 2018, a committee of experts will report on the potential use of biotechnology to mitigate threats to forest tree health; identify the ecological, ethical, and social implications of deploying biotechnology in forests, and develop a research agenda to address knowledge gaps about its application. Funding for the study has been provided by The U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities; several agencies within the U.S. Department of Agriculture – Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Forest Service, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Committee meetings are webcast, and there are other webinars on pertinent topics. You can view the schedule and sign up to receive alerts here.

Several people actively engaged in finding answers to invasive pest challenges have presented their views to the Committee, including Gary Lovett, Deb McCullough, Richard Sniezko, and me (!). You can find our presentations (Powerpoints and oral) at the above website. My talk focused on the crisis posed by non-native insects and pathogens and the need to evaluate the full range of possible response strategies for each host-pest situation. Application of genetic engineering technologies – in the absence of adequate resources for research and deployment of resistant hosts – cannot result in restoration of the host trees.

Background Information

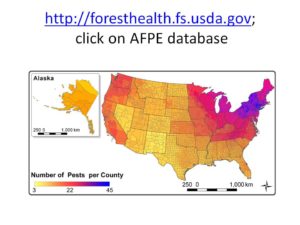

Examples of tree-killing pests include such famous examples as chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease as well as less-well-known pests as soapberry borer. This map

indicates how many of the most damaging pests are established in each county of the 49 conterminous states. Descriptions of some of these insects and pathogens are provided here.

Additional tree-killing pests not included in the sources for the data supporting the map for various reasons would add to the numbers of pests in some states. Some non-native organisms have been introduced too recently, others attack palms or trees in Hawai`i; still others are native to Mexico and parts of the United States so were not included.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.