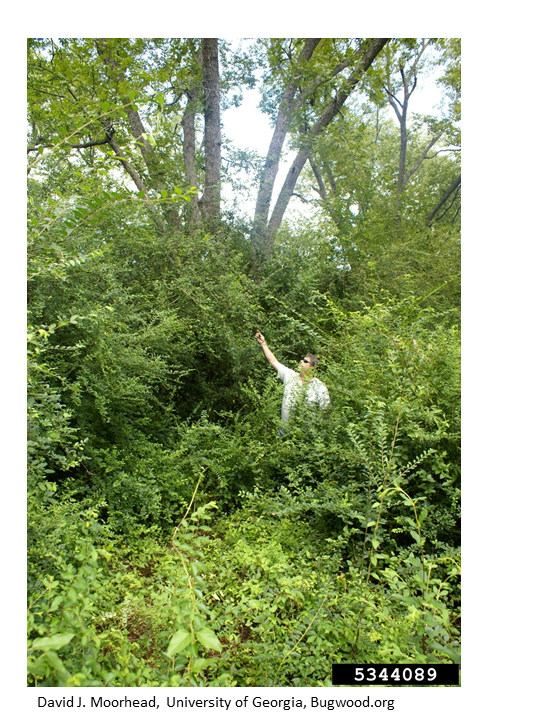

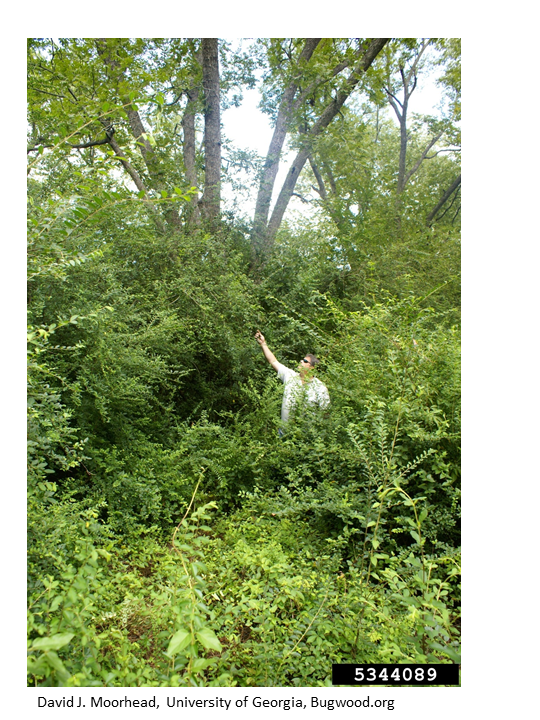

A decade ago I posted a blog reporting that 39% of forests surveyed under the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) system were invaded by one or more invasive plants (Oswald et al. 2015). By regions, Hawai`i had the highest invasion intensity – 70%. The second highest density was in the eastern forests – 46%. Forests in the West ranked third, with 11% of plots containing at least one of the monitored invasive plant species. Finally, forests in Alaska and the Intermountain regions both had 6% of plots invaded.

I rejoice that US Forest Service scientists have continued to analyze their data on plant invasions. Analysis of the most recent data shows alarming increases in invasions everywhere since 2015. However, the scientists could not determine a nation-wide percentage because many areas in the West had not yet been surveyed anew. They did determine that the number of inventory plots containing invasive plant species rose in 58.9% of surveyed counties. Furthermore, in 73.2% of the counties the plots experienced an increase in species richness of invading plant species. While increases were observed in all regions, they were greater in the East than in the West — and in the USFS Southern region compared to the Northern region. Specifically, the proportion of forest plots in the East (USFS Southern and Northern regions) invaded has risen from 46% to 52.8%. In the Rocky Mountains they rose from 6% to 11%. In Hawai`i plots having invasive plants grew from 70% to 83.2%. Surveys in the Pacific Coast states have not yet been completed so this region is not included in the analysis (Potter et al. 2026). It is not clear to me how the current boundaries of the western regions – which are based on Bailey’s ecosystem boundaries relate to the 2015 boundaries, which were based on USFS official regions. Hawai`i is clearly the same.

Porter et al. (2026) concluded that in the forests of the East plant invasions are so extensive that elimination of their impacts is practically impossible. Their spread to new areas is unhindered now and, I would add, is likely to remain so without heroic counter measures.

Forests in the East have a greater mean richness of invasive plant species than do western forests. In particular, there is a profusion of shrubs and vines as well as trees. The West has a greater diversity of invasive forbs. The diversity of invasive grasses is high in both regions.

Potter at al. (2026) worry that the apparently lower level of plant invasions in the West might be an artifact of a higher proportion of plant species being at an earlier stage of invasion. That is, the species have not yet established sufficiently widely to be classified as invasive.

ohia killed by ROD; Hawai`i Island; photo by F.T. CampbellOf course, the situation in Hawai`i is much worse. Another, more detailed, discussion of invasive plant species in Hawai`i pointed out that relying on data reflecting canopy-level trees obscures the real picture. While “only” 29% of large trees across the Islands are non-native, about two-thirds of saplings and seedlings are. Potter et al. (2023) expected that plant succession will result in non-native tree species taking over the canopy. This likelihood exists regardless of the impact of rapid ‘ohi’a death since ‘ohi’a lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) is not reproducing even when seed sources are plentiful and people remove invasive forbs and grasses Potter et al. (2023).

The nation-wide analysis of Potter et al. (2026) does not include forests on U.S. Caribbean islands, i.e., Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. See here for a description of this situation. In summary, 33 of 57 (58%) of non-native tree species tallied by FIA surveyors are actual or potential high-impact bioinvaders. Furthermore, 21 (38%) of the non-native species occurred on at least 2% of the FIA plots – far above the seven species fitting this description in the continental U.S.

As these sources, and those with a broader perspective, demonstrate that we should not ignore invasions of our forests by non-native plants. These species erode forest productivity and provision of the full range of ecosystem services, hinder shifting (?) forest uses, and degrade biodiversity and habitat.

These invasions also impose extensive financial costs from lost or damaged resources (Potter et al. ( 2022). Potter et al. (2026) note that these negative outcomes depend on interactions between the traits of the non-native plants and the biomes being invaded. These impacts are greatly exacerbated in Hawai`i because more than 95% of native species on the Islands are endemic. This includes 67% of the large trees still present in the forests. As Potter et al. (2023) point out, extirpation of any of these species is a global loss.

Data issues

Potter et al. (2026) note that in the Northern region only about 20% of plots were surveyed for invasive plants. They state that these difference in sampling intensity does not affect statistical analyses across broad scales.

The regional lists of invasive plants were developed by experts. They include those species thought at the time to be most damaging. Of course, there are other non-native plant species that might be present – and some might prove to be invasive over time (Potter et al. 2026). I have been unable to determine whether the regional lists are updated periodically. Because of this structure of the FIA system, these surveys can assess only spread of already-established species. It is not suitable for early detection of new species entering the forest.

For all these reasons, the analyses in Porter et al. (2026) probably underestimate the total abundance of non-native plant species in U.S. forests. Indeed, the time lag between introduction or even identification of invasive species and their eventual ecological and economic impact obscures their full impact. This ever-increasing invasion debt probably contributes to decisions not to implement effective countermeasures.

Recommendations

How do we set priorities for responding to nearly unmanageable situations? We sharpen our focus on the most damaging pathways of introduction, the most vulnerable regions, and the most at-risk species.

The high-risk pathways are imports of plants for planting and wood – including but not limited to crates, pallets, and other forms of packaging.

Vulnerable regions start with the Hawaiian Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands; and include many biodiversity-rich areas on the continent. We should enhance monitoring of these vulnerable regions by federal, state, and tribal agencies, conservation organizations, citizen scientists, and others. Surveys must report all non-native plant present, not just those already known to be invasive. These data will improve detection of new species and better inform us about factors affecting species’ spread.

Also, I support Potter et al.’s (2026) emphasis on the wildland-urban interface as an area of high human-environment conflict.These include, but are not limited to, plant invasions. The authors point out that we need new policy, management, and scientific tools to address threats in these vulnerable and too-often ignored social and ecological zones.

This increase in available information must be paired with management of the factors that facilitate invasion. Some of these are associated with ecosystems. But the key target must be plant species being brought into the region by people for various purposes. This is often for ornamental horticulture.

We must ask state legislatures and Congress to empower regulatory agencies – e.g., their state departments of agriculture and USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service – to be far more more assertive and pro-active. For example, they must give higher priority to the full range of ecological and economic impacts of invading plants, not just damage to agriculture.

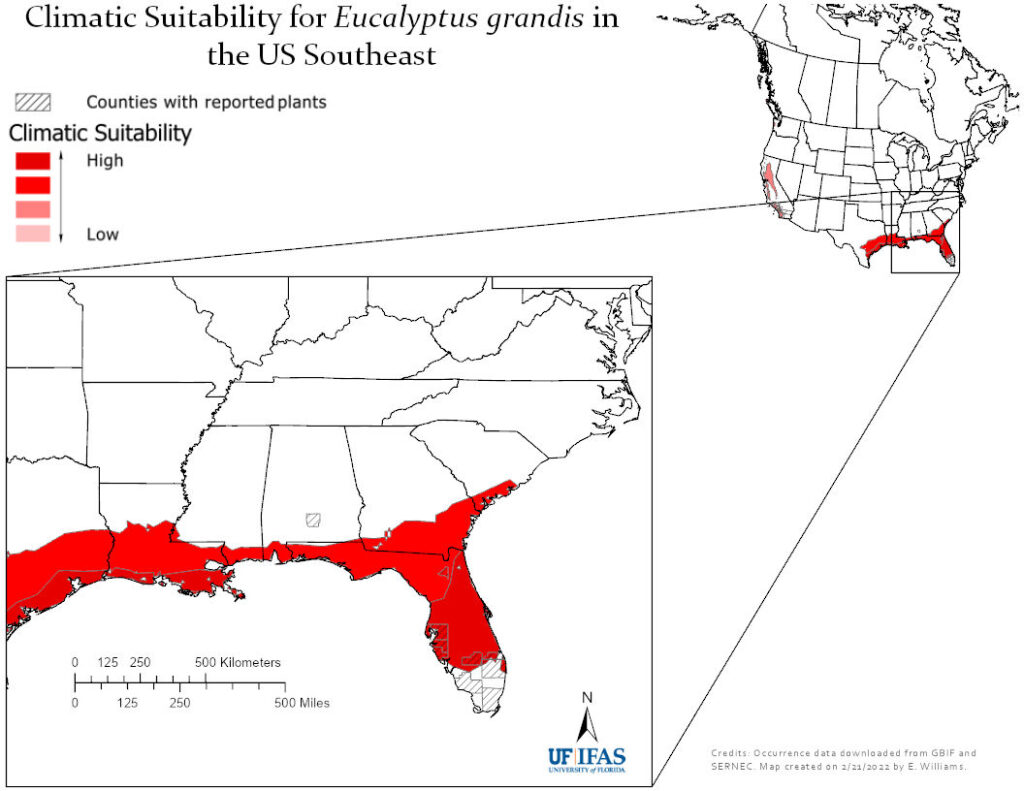

Evans et al. (2024) urged prioritizing for state regulation those species in the ornamental trade that are projected to remain or become abundant under evolving climate conditions. Beaury et al. (2023) called for regulating the nursery trade at the national level – reflecting the scope of sales.

SOURCES

Beaury, E.M., J.M. Allen, A.E. Evans, M.E. Fertakos, W.G. Pfadenhauer, B.A. Bradley. 2023. Horticulture could facilitate invasive plant range infilling and range expansion with climate change. BioScience 2023 0 1-8 https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biad069

Evans, A.E., C.S. Jarnevich, E.M. Beaury, P.S. Engelstad, N.B. Teich, J.M. LaRoe, B.A. Bradley. 2024. Shifting hotspots: Climate change projected to drive contractions and expansions of invasive plant abundance habitats. Diversity and Distributions 2024;30:4154

Potter, K.M., C. Giardina, R.F. Hughes, S. Cordell, O. Kuegler, A. Koch, E. Yuen. 2023. How invaded are Hawaiian forests? Non-native understory tree dominance signals potential canopy replacement. Landsc Ecol 2023 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-023-01662-6

Potter, K.M., B.V. Iannone III, K.H. Riitters, Q. Guo, K. Pandit, C.M. Oswalt. 2026. US Forests are Increasingly Invaded by Problematic Non-Native Plants. Forest Ecology and Management 599 (2026) 123281

Potter K.M., K.H. Riitters, and Q Guo. 2022. Non-native tree regeneration indicates regional and national risks from current invasions. Frontiers in Forests & Global Change Front. For. Glob. Change 5:966407. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2022.966407

Potter, K.M., K.H. Riitters, B.V. Iannone, III, Q. Guo and S. Fei. 2024. Forest plant invasions in eastern US: evidence of invasion debt in the wildland‑urban interface. Landsc Ecol (2024) 39:207 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-024-01985-y

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

Or