Are the Rules Working?

APHIS adopted a new approach to regulating interstate trade in SOD hosts in early 2014. One year later, spring 2015, it is too soon to provide a thorough evaluation of whether this approach is effective in ending the risk that the disease will be moved to new areas on nursery plants. But some problems have already shown up, suggesting that the approach has serious weaknesses and will not succeed as intended.

1) APHIS’s new program is unlikely to find either new or cryptic infestations quickly.

When APHIS put its program into force in March 2014, 23 nurseries in California, Oregon, and Washington that had tested positive for the pathogen in the previous three years signed up to participate in the program – thus complying with the requirements for continuing to ship SOD host plants interstate. By the end of 2014, three of those nurseries had dropped out – so they can now ship plants only to retailers/purchasers within their states. A fourth nursery was expelled from the program because of its continuing inability to eradicate the pathogen from its premises. This nursery is no longer allowed to ship SOD hosts out of state.

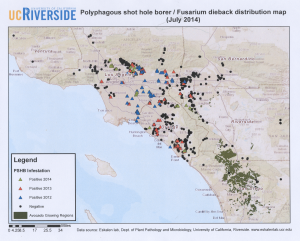

At the same time, two additional nurseries joined the program. So as of the end of 2014, 21 nurseries were participating. Seven participating nurseries are in California; all have tested free of the pathogen in spring 2015. Ten participating nurseries are in Oregon; four of these nurseries tested positive for the pathogen in spring 2015.

Many more nurseries in the three states that had been tested for the pathogen over the past three years and found not to be infested are now allowed to ship plants interstate without being subject to the new APHIS requirements. (For example, in 2013 California tested plants in 1,575 nurseries; only one positive nursery was found.) The issue now is whether these nurseries are truly clean of the pathogen, and will remain so. Since the SOD pathogen was extremely difficult to detect in plants (the system relied upon before 2014), I am concerned that nurseries that tested “clean” before 2014 might have harbored a cryptic infestation that escaped detection.

Such cryptic pre-existing infestations – and any new infestation that establishes in a nursery not currently subject to the regulation due to a previous infestation – will probably escape detection for months because, under the current APHIS program, the presence of SOD in these nurseries will be detected only under one of the following conditions:

- The nursery owner reports symptoms of infestation;

- The state detects symptomatic plants during a routine state inspection; or

- The nursery is identified as the source of infested plants purchased by someone (this is called a trace-back investigation).

Some nurseries that had been shipping SOD host plants interstate under the previous APHIS regulations chose to stop shipping host plants interstate and so did not agree to abide by the new requirements. I know that five Oregon nurseries opted out; APHIS has not told me how many nurseries in California and Washington also opted out.

picture of infested rhododendron plant;

courtesy of Jennifer Parke, Oregon State University

- The risk that nursery plants will spread SOD continues.

How large is this risk? One measure is how many nurseries are infested with the disease – either through a new introduction or as a result of an earlier infestation that was not detected.

During 2014, state inspectors detected the SOD pathogen in 19 nurseries – almost the same number as in 2013, and slightly more than half the number in 2012. (For a discussion of the SOD pathogen in nurseries in recent years, read Chapter V in Fading Forests III. Eleven of these nurseries were in the three west-coast states that have been regulated most tightly in the past (CA-1, OR-8, WA-2); eight nurseries were in other parts of the country (ME-1, NY-2, TX-1, and VA-4).

Fourteen of the 19 nurseries had tested positive for the pathogen during the previous three years. Consequently, they had been subject to the new regulation from its implementation.

However, two nurseries had tested positive before 2011, but not during the key 2011-2013 period. Under the terms of the 2014 regulation, these nurseries were not subject to APHIS’s new regulation and they continued to ship plants. This raises concerns about whether infestations in some nurseries might not be detected under the new regime before they ship plants to disease-free areas.

Eight of the 19 infested nurseries were interstate shippers (CA-1; OR-4; WA-1; TX-1; VA-1). Six had shipped plants in the previous six months.

Five of these infested interstate shippers stayed in the new APHIS program, carried out Critical Control Point Assessments, and adopted specific mitigation actions that were approved by APHIS and state officials. They continue to ship SOD host plants interstate.

Four of the eight infested nurseries left the program, either voluntarily or by compulsion. Nurseries not in the APHIS program may now ship SOD host plants only to destinations within their states; they are subject to regulation by their state agencies (usually, departments of agriculture).

Eleven of the nurseries detected to be infested by the SOD pathogen in 2014 shipped only to retailers within their own states; these nurseries are regulated by the appropriate state rather than by APHIS.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the New Regime

So, what do I see as the strengths of the new regulatory regime? Most important, inspectors test the soil, water, and pots, not just symptomatic plants. This approach, recommended by scientists for years before APHIS adopted it, is paying off: inspections detected the pathogen twice in potting media, six times in a nursery’s soil, and 15 times in water on nursery premises.

The greatest weakness is the three-year cutoff for including nurseries in the APHIS program; as demonstrated already, nurseries can be clean for three years and then again be found to be infested. It has always been difficult to determine whether these “repeat” nurseries were infested all along, but somehow escaped detection; or have become infested through a new introduction of the pathogen.

Questions also arise because of the reliance on state regulation of nurseries shipping only within the state. Some state agencies appear to be much more aggressive than others in searching for symptoms of infestation and requiring cleanup.

Another possible problem is that the regulatory inspection effort focuses on five genera — Camellia, Kalmia, Pieris, Rhododendron, and Viburnum — but plants in other genera are also hosts. During 2014, detections were made on the following genera that are not among the “high-risk” hosts — Gaultheria, Prunus, Syringa and Vaccinium; and seven new host species were detected in the forest or in nurseries. One of these apparently new hosts, Vinca, is a widely planted ground cover (“periwinkle”) shipped in flats of often sad-looking rooted cuttings.

One good sign is that the nursery trade and state agricultural agencies are seeking ways to decrease the movement of plant pests via the nursery trade. Examples of such pest movement are not limited to SOD or other tree-killing pests; for example, boxwood blight was first detected in the United States in 2011; by 2013 it was known to be in nine eastern states and Oregon.

The nursery trade (through their trade associations, AmericanHort and the Society of American Florists), state agencies, and APHIS have developed a voluntary program called Systems Approach to Nursery Certification, or SANC. The collaborating organizations devoted several years to developing an agreed-upon set of standards and procedures aimed at making their facilities as free of disease and pests as possible. Now they are testing whether the program works in practice. Eight plant growers from across the country – and the appropriate state agencies – have agreed to:

- Assess the facility for situations and practices that create a risk of pest infestation;

- Identify best management practices that will mitigate those risks; and

- Develop new facility-management manuals that apply those practices.

The SANC managers expect the pilot program to take 3 years (2018).

The principal sources for the information in this blog are the monthly newsletters prepared by the California Oak Mortality Task Force (COMTF), found at http://www.suddenoakdeath.org/ and the USDA APHIS program updates found at http://www.aphis.usda.gov/wps/portal/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/sa_domestic_pests_and_diseases/sa_pests_and_diseases/sa_plant_disease/sa_pram/ct_phytophthora_ramorum_sudden_oak_death/