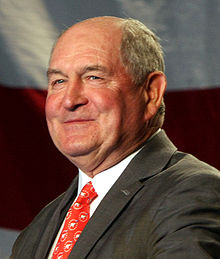

Secretary of Agriculture nominee Sonny Perdue

Former Governor of Georgia Sonny Perdue was President Trump’s last pick for his cabinet. His long-delayed confirmation hearing took place before the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry on March 23, with at least 18 of the 21 members present for at least some of the time. He’s likely to be confirmed easily, given support from 700 agricultural organizations and six former USDA secretaries. However, final approval could take several weeks, given the time needed to answer senators’ follow-up written questions and a looming congressional recess.

In his opening statement, the nominee named four goals: creating jobs, making customer service a priority, keeping food safe for consumers, and ensuring stewardship of American lands. (Mr. Perdue’s statement and video of the full hearing are on the Committee’s website.)

The hearing was friendly – except to the President’s proposed budget, which calls for a 21 percent cut in USDA’s discretionary spending. Ranking Minority Member Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) said the budget makes it clear that “rural America is an afterthought.” But Chair Pat Roberts (R-KS) and others noted that “the President proposes and Congress disposes,” with a nod down the table to Sen. John Hoeven (R-ND), who chairs the Senate Appropriations Committee’s agriculture subcommittee. Sens. Thad Cochran (R-MS), Mitch McConnell (R-KY), and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) — each with considerable seniority — serve on the same subcommittee.

Phytosanitary policy did not come up — although CISP and others provided lists of potential questions on the topic to several senators. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) did ask how to stop the spread of avian influenza, detected in Tennessee, Wisconsin, and Alabama. Gov. Perdue seemed confident, saying U.S. poultry exports are critical and we’d learned to respond quickly. (Four days later the disease was detected in chickens in Georgia.)

Few USDA agencies were mentioned by name. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) was among those not mentioned. In response to questions, Gov. Perdue did voice support for “critical” research and extension done by the Natural Resource Conservation Service and said, in defense of the National Agricultural Statistical Service (NASS), that farmers need “independent, trusted sources” of information. Sen. John Thune (R-SD) asked about the potential of pathogen-laden meat imports from Brazil. Perdue noted that the Food Safety and Inspection Service “wants to go to” 100% inspection (a policy announced March 22) but a beef embargo would risk retaliation.

Mostly, specific programs were named only if they were targeted by the President for cuts (like NASS). Efforts to clean up agricultural runoff that pollutes the Chesapeake Bay and the Great Lakes; work to stem rural opioid addiction; and initiatives for rural clean water all fall into this group.

Only the U.S. Forest Service received more than passing attention. Its management of national forests was criticized. Several senators noted the crisis in funding fire-fighting. Forests, Gov. Perdue said, provide “opportunities clothed in challenges,” e.g., to implement best management practices and be better neighbors. Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT) urged him to restore active management of forests, as well as to limit litigation by “extremist groups.” Perdue sympathized.

Several themes came up repeatedly:

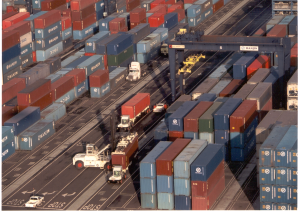

- The importance of foreign trade. Chair Roberts wants agriculture at the top of priorities for the new White House National Trade Council. Gov. Perdue has already met with the U.S. Trade Representative and Secretary of Commerce and aims to “sell [the country’s] bounty” in expanding markets.

- The need for the secretary to be an unapologetic advocate for agriculture within the Administration. Gov. Perdue promised to be a “tireless salesman.” Hope that Perdue would support ideas proposed for the 2018 Farm Bill. These include expanding crop insurance for growers of specialty crops and the dairy industry; ensuring immigration/visa policy that supports year-round access to labor for dairy farms; providing summer nutrition programs for students.

- Changing regulations that were called, variously, costly, hard-to-understand, or very onerous. As secretary, Perdue would “incentivize producers” to conserve without “onerous prescriptive regulations” (like those on wetlands; he has met with the new EPA Administrator).

- Members’ requests that he visit their states — in some cases for public meetings on the new Farm Bill.

Generally, Mr. Perdue was agreeable — e.g., toward a stronger renewable fuel standard and better rural broadband access — or at least found Members’ suggestions “intriguing”. He promised to provide resources to help with the new farm bill and to further implement the 2014 one, either more fully (as Sen. Klobuchar requested) or more flexibly (as Sen. Thune did). Gov. Perdue confessed “some concern” about proposed budget cuts, for example, to agricultural research, organic agriculture, telemedicine, and nutrition programs — a list supplied by Sen. Stabenow. He cited his experience working within tight budgets in Georgia, though, and expects to do the same at USDA. He said that he was a “facts-based, data-based decision-maker.”

Gov. Perdue grew up on a dairy farm, is a veterinarian, and runs several agribusinesses. The latter got him in trouble, as Georgia governor, with the state’s ethics commission. He has agreed to put his businesses in trust if confirmed. These concerns did not come up in the hearing. Nor did his controversial views on climate change, although Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) noted the connection between fire and climate change and said climate change must be addressed. One person was ejected from the hearing after protesting animal agriculture.

Present:

Chair Roberts (R-KS); Cochran (R-MS); Boozman (R-AK); Hoeven (R-ND); Ernst (R-IA); Thune (R-SD); Daines (R-MT); Perdue (R-GA – the nominee’s cousin); Strange (R-AL).

Ranking Member Stabenow (D-MI); Leahy (D-VT); Klobuchar (D-MN); Brown (D-OH); Bennet (D-CO); Gillibrand (D-NY); Donnelly (D-IN); Heitkamp (D-ND); Van Hollen (D-MD).

Our comment:

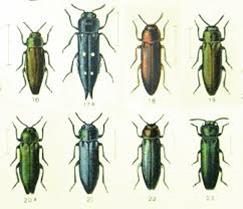

We are disappointed that no one asked a single question about introduced pests or weeds. Nine of the senators present are from states already suffering severe tree mortality caused by the emerald ash borer; four more are from states that will soon see significant losses to that pest. All are from states in which invasive plants are often said to threaten agricultural production and/or natural resources.

Perhaps some questions will be put to Mr. Perdue in writing.

The combination of silence on phytosanitary issues and emphasis on the importance of trade seems to promise a continuation of imbalances that favor trade promotion at the expense of vigorous phytosanitary measures. If USDA leadership is focused on promoting export markets for U.S. agricultural producers, it will be difficult to persuade the agency to adopt and enforce effective tools to prevent pest introductions.

For more information:

DelReal, J.A. 2017. “Senators press Perdue on USDA budget. The Washington Post , March 24, p. A10. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/senators-grill-agriculture-nominee-sonny-perdue-on-trumps-proposed-cuts-to-rural-programs/2017

Sheinin, A.G., “Bird flu found in Georgia chicken flock.” Atlanta Journal Constitution. March 27, 2017. http://www.ajc.com/news/state–regional-govt–politics/bird-flu-found-georgia-chicken-flock/DGgBp1sUhctO6JLDLLyIFJ/

Sullivan, B.D., Sonny Perdue gets friendly reception during Agriculture secretary hearing, USA TODAY March 23, 2017. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/03/23/sonny-perdue-gets-friendly-reception-during-hearing-agriculture-secretary/99548680/

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “USDA on tainted Brazilian meat: none has entered U.S., 100 percent re-inspection instituted.” Press release, March 22, 2017. https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2017/03/22/usda-tainted-brazilian-meat-none-has-entered-us-100-percent-re

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Posted by Phyllis Windle and Faith Campbell

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org