As we know, non-native insects and pathogens pose a significant and accelerating threat to biodiversity in forests and other ecosystems. They undermine some conservation programs and reduce ecosystem services and quality of life in urban areas. Nevertheless, damaging introductions continue.

Two recent articles have advocated accelerating biocontrol programs. These articles have reminded us of ongoing failures of international and national biosecurity programs, including that of the US. The articles also make interesting suggestions regarding ways to be more pro-active in preventing introductions.

1. “Self-introductions” of invaders’ enemies

Weber et al. (full citation at end of blog) provide many examples of unintentional “self-introductions” of natural enemies of arthropod pests and invasive plants. In fact, “self-introductions” of natural enemies of arthropod pests might exceed the number of species introduced intentionally. These introductions have been facilitated by the usual factors: the general surge in international trade; lack of surveillance for species that are not associated with live plants or animals; inability to detect or intercept microorganisms; huge invasive host populations that allow rapid establishment of their accidentally introduced natural enemies; and lack of aggressive screening for pests already established.

Among the examples illustrating failures of biosecurity programs:

- Across six global regions, nearly two-thirds of parasitoid Hymenoptera species were introduced unintentionally. The proportion varies significantly by region. For example, four-fifths of these insects in New Zealand arrived accidentally.

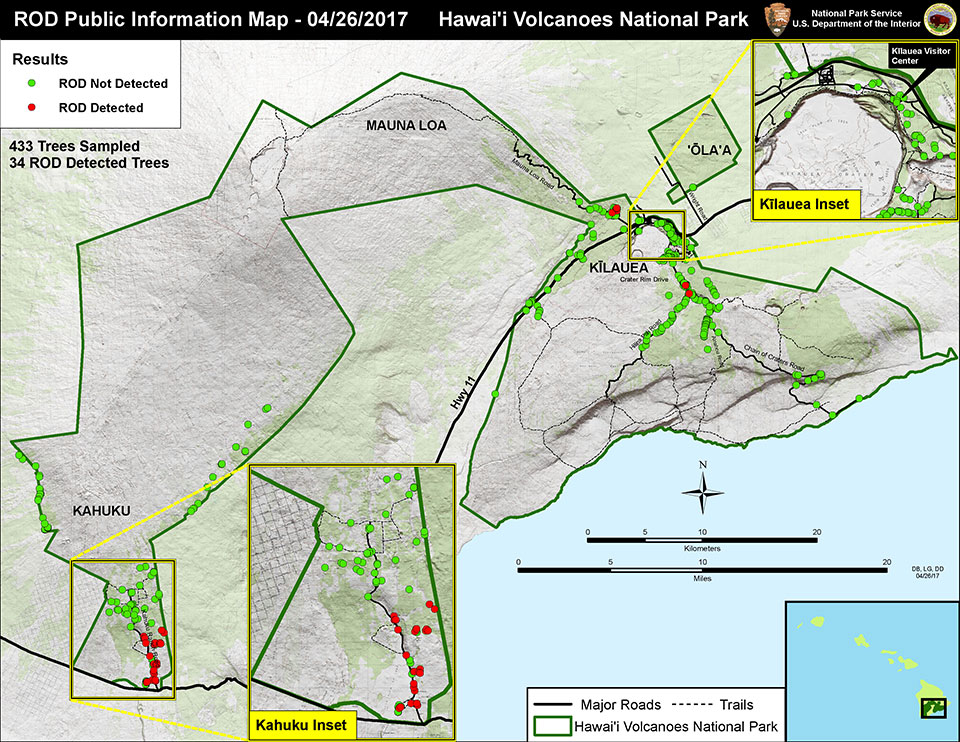

- The unintentional spread of the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis) and a biocontrol agent Cosmocomoidea ashmeadi has been so rapid among islands in the Pacific Ocean (including Hawai`i) they are considered ‘biomarkers’ of biosecurity failures.

- Regarding the United States specifically, an estimated 67% of beneficial insects introduced to Hawai`i and 64% of parasitoid Hymenoptera introduced to the mainland U.S. were accidental “self-introductions.”

Weber et al. consider their figures to be underestimates. The situation is particularly uncertain regarding pathogens that kill arthropods. Many microbial species are not yet described.

In some cases, these “self-introduced” arthropods have proved beneficial. Two examples are Entomophaga maimaiga and Lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus (LdNPV), which help control the spongy moth (Lymantria dispar). In other cases the “self-introduced” creatures are pests themselves. A prominent example is the invasion by the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula). This was facilitated by the widespread presence of the highly invasive plant Ailanthus altissima. It illustrates what Weber et al. call “receptive bridgehead effects.” That is, once an invasive pest is well-established, the chance that its natural enemies will find a suitable host and also establish in the pest’s invaded range is much higher.

Weber et al. reaffirm that there are many good reasons not to allow such random invasions of diverse non-native species – including their natural enemies. Deliberately introduced biocontrol agents are chosen after determining their efficacy, host-specificity, and climatic suitability. Random introductions, on the other hand, might favor generalist species, which could threaten non-target species. Accidental introductions might also be accompanied by pathogens and hyperparasitoids that could compromise the efficacy of biocontrol agents.

In short, unintentionally introduced natural enemies might have about the same level of success in controlling the target pest’s populations as do intentionally introduced agents. However, unintentional introductions of both pests and pathogens carry additional risks of non-target impacts and contamination with their own natural enemies that would hamper the efficacy of the biocontrol agent. Weber et al. conclude that delays in releasing a deliberately chosen and evaluated biocontrol agent reduce the probability that it will successfully establish instead of an unintentionally introduced organism.

It is especially likely that an arthropod – whether or not a biocontrol agent – will spread within a geographic region. Weber et al. say both the U.S. and Canada have received more than a dozen species intentionally introduced into the other country. They also cite spread of the cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum, into Florida from several Caribbean countries. The cactus moth has spread and now threatens the center of diversity of flat-padded Opuntia cacti in the American southwest and Mexico.

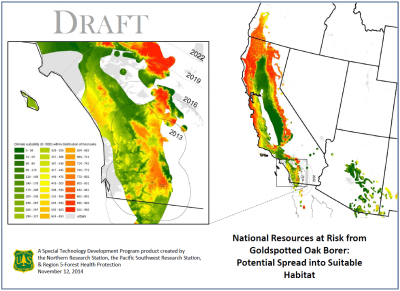

Another example is California: 44% of invading terrestrial macroinvertebrates that have established in the state came from populations established elsewhere in the US and Canada (Hoddle 2023). This number exceeds the total number of invasive macroinvertebrates in the state that originated anywhere in Eurasia (Weber et al.).

True, it is very difficult to prevent natural spread. But a lot of this spread is facilitated by human activities, e.g., transporting vectors such as living plants, firewood, outdoor furniture or storage “pods.” I have complained often — here and here and here — that interstate movement of invasive plant pests is particularly poorly controlled.

Some scientists and regulators have responded to these situations by improving phytosanitary programs. California officials, in 2019, set up a program to fund projects aimed at developing integrated pest management strategies for species thought to have a high invasion potential before they arrive. I urge other states to do the same. This would probably be most effective in controlling the target species – and in relation to cost — if developed by regional consortia.

Weber et al. suggest that given continuing unintentional introductions of non-native species, phytosanitary agencies need to focus on those invasion pathways that are particularly likely to result in invasions, e.g. live plants, raw lumber (including wood packaging), and bulk commodities e.g. quarried rock.

The authors also suggest research opportunities that arise from biocontrol agents’ “self-introductions”. These include:

- Comparing actual host ranges to those predicted by laboratory and other studies;

- Quantifying the role of Allee effects, for example by studying the spread of the glassy-winged sharpshooter and its biocontrol agent across the Pacific region;

- Using molecular analyses to disentangle multiple routes of entry (e.g., the “invasive bridgehead effect”) and hybridization.

2. Door-knocker species

Hoddle (2023) suggests further that early detection programs should focus on “door-knocker” species — those likely to enter and cause significant negative impacts. In an earlier article (Hoddle, Mace and Steggall 2018) argued that the benefits of a pro-active biocontrol program outweigh the costs. The authors say the information gained would cut the time needed to deploy effective biocontrol. Ultimately, this could reduce the prolonged and even irreversible ecological and economic disruption from invasive pests, associated pesticide applications, and lost ecological services.

Hoddle calls funding pro-active biocontrol research programs before they’re needed as analogous to buying insurance. The owners of insurance policies hope not to need them but benefit when catastrophe strikes. Furthermore, the information gained from early research might identify natural enemy species that could “self-introduce” along with the invading host. Finally, proactive research might clarify whether the increasing number of natural enemy species that are “self-introducing” pose a threat to non-target organisms.

Recognizing the difficulty of identifying an “emerging invasive species” before its introduction, Hoddle endorses other components of prevention programs:

- Collaborating with non-U.S. scientists to identify and mitigate invasion bridgeheads. Such efforts would both lessen bioinvasion threats and possibly aid in determining native ranges and facilitating location of natural enemies.

- Sentinel plantings, such as those established under the International Plant Sentinel Network. These plantings can also support research on natural enemies of key pests.

- Integrating online platforms, networks, professional meetings, and incursion monitoring programs into “horizon scans” for potential invasive species. He mentions specifically PestLens; online community science platforms, e.g., iNaturalist; international symposia; and official pest surveillance, e.g., U.S. Forest Service’s bark beetles survey and surveys done by the California Department of Food and Agriculture and border protection stations.

Weber et al. also support the concept of sentinel plant nurseries – especially because accidental plant and herbivore invasions often occur at the same points of entry.

Both Weber et al. and Hoddle urge authorities not to strengthen regulations governing biocontrol introductions. Weber et al. say that would be to make perfect the enemy of the good. The need is to balance solving problems with avoiding creation of new problems.

SOURCES

Hoddle, M.S., K. Mace, J. Steggall. 2018. Proactive biological control: A cost-effective management option for invasive pests. California Agriculture. Volume 72, No. 3

Hoddle. M.S. 2023. A new paradigm: proactive biological control of invasive insect pests. BioControl https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-023-10206-5

Weber, D.C. A.E. Hajek, K.A. Hoelmer, U. Schaffner, P.G. Mason, R. Stouthamer, E.J. Talamas, M. Buffington, M.S. Hoddle, and T. Haye. 2020. Unintentional Biological Control Chapter for USDA Agriculture Research Service. Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory. https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=362852

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or