I, and many others, have given much attention to the emerald ash borer (EAB), a species in the Agrilus genus. This attention is deserved. In 30 years EAB has spread from then-localized infestations in Michigan and Ontario to natural and urban ash ecosystems across North America. The EAB is spreading in Europe, too.

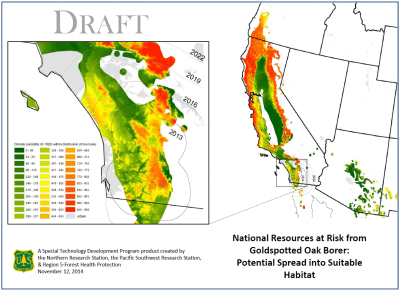

We have paid far less attention to a second Agrilus, the goldspotted oak borer (GSOB), Agrilus auroguttatus. In roughly 30 years, the GSOB infestation has become the primary agent of oak mortality across much of southern California, an area of roughly 37 million square miles. This is bigger than the combined land areas of West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware.

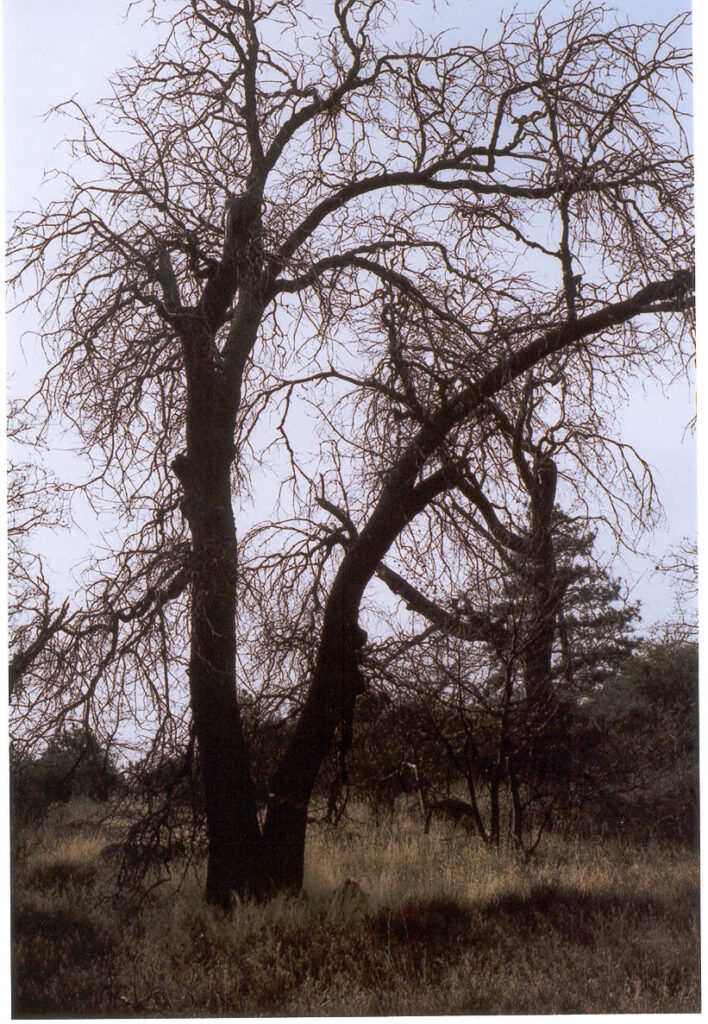

While the number of trees killed has generally expanded slowly, there have been periods of explosive growth. For example, annual mortality was estimated to have reached 40,000 trees in 2017. The officially documented cumulative total is over 142,000. At least one scientist, Joelene Tamm, considers this number to be a significant underestimate; she estimates the true number of trees killed as probably close to 200,000. As she explains (see here), the USFS’ Aerial Detection Surveys is not very effective at capturing mortality within fragmented urban landscapes, narrow riparian corridors, or when the target species have sprawling canopies (as oaks do).

Ravaged oak forests grow on five mountain ranges. People losing valuable resources and paying to manage the invasion include

- U.S. taxpayers — three National forests have lost oaks; a fourth Forest is on the brink;

- Residents of California – trees killed in at least four State parks, 10 County parks, and two major private reserves;

- Native Americans on at least five reservations

- City dwellers and property owners: up to 300,000 coast live oak trees live in built-up sections of just one heavily infested city, Los Angeles.

This damage is almost guaranteed to spread in the future. Three oak species host GSOB: coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), California black oak (Q. kelloggii), and canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis). The ranges of black and canyon live oak stretch north along the Coastal Mountain Range and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range into southwest Oregon. The range of coast live oak reaches Mendocino County. A risk assessment concluded that GSOB could invade all these regions. Among urban areas, Santa Barbara faces the highest risk because of the large number of oaks in its urban forest. While this county has not yet been invaded by GSOB, the beetle is now in adjacent Ventura County – although at the other end of the county.

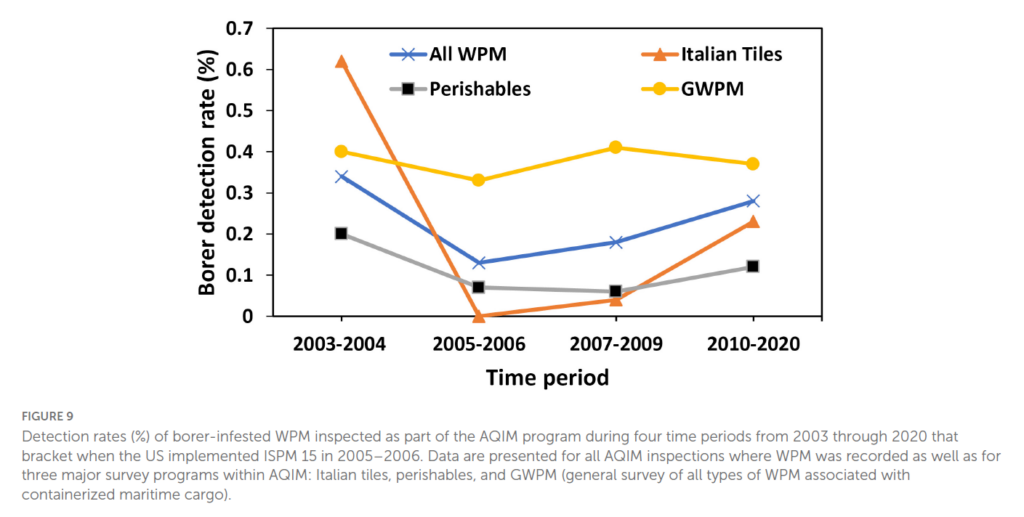

GSOB is transported to new locations primarily by the movement of firewood. This means of human-assisted spread almost certainly explains its initial introduction to from southeastern Arizona to California – in eastern San Diego County – in the 1990s. (See here for the explanation why it is unlikely that the beetle would have spread to California through natural dispersal.) It is blamed for the establishment of numerous disjunct populations that propelled its spread. These outbreaks led to recognition of invasions in additional counties in new counties in 2012, 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2024.

Death of these trees causes numerous ecological impacts. Oaks provide food, habitat, and climate control for hundreds of species. Oak mortality also increases the probability and severity of wildfire. The few natural enemies, including woodpeckers and some parasitoids, are not keeping GSOB populations in check. Urban trees provide important ecological services, including shade which reduces energy use and expense associated with air conditioning; they also reduce storm water runoff. Larger trees – those preferred by GSOB – provide more of these services. Dead oaks not only deny people of these services; they also demand prompt removal to prevent them falling on people or structures; this is done at considerable expense.

GSOB invasions are now known to be present in six counties: San Diego, Orange, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura. Since the state has opted out of leading management of the beetle (see below), coordination of these many players presents significant challenges on top of the usual difficulties that hinder most U.S. efforts to reduce threats from non-native forest insects and pathogens:

- Detection of outbreaks occurs years after the pest’s actual introduction. Locations of disjunct outbreaks are difficult to predict. They fuel more rapid dispersal.

- The host species are not important commercial timber sources, so key forest stakeholders do not act – despite the tree species’ great ecological importance.

- USDA APHIS does not engage because GSOB has become a non-native tree-killing organism in a single state (although it was introduced from a separate state – Arizona).

Problems more specific to GSOB are:

- Some authorities dismiss this invasion because the beetle is native in one U.S. state.

- California State agencies and the National Park Service have not taken effective action to control movement of the principal vector – in this case, firewood.

Fortunately, a broadening alliance of locals is trying to fill the gaps. These efforts are truly encouraging. Concerned individuals and organizations in Southern California have put together a broad coalition that works to ensure an outbreak-wide response. Participants include staffers in the USDA’s Forest Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service; the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs; CalFire; California Department of Conservation; State parks; agencies of four counties; community Fire Safe councils; regional conservation agencies; several Resource Conservation districts; various Tribes and Tribal Nations; and University of California extension. In some counties, there are also geographically-focused coordinating bodies.

Money is scarce, but somehow they manage to carry out detection and monitoring, vigorous outreach and education projects, and — at some sites — treatment of vulnerable trees and removal of “amplifier” trees. Teams working under the umbrella of this coalition have developed GSOB-killing treatments for logs (firewood); search for tools to increase survey efficacy; investigate the area-wide impact of the beetle, and its interaction with drought. Scientists have also explored possible biocontrol agents in the species’ native habitat in Arizona. However, the two parasitic wasps found there are already present in California, where their parasitism rates are much lower.

Some of the participants have been willing to “go political” in search of resources and official actions.

Might this coalition be a model for addressing other pests?

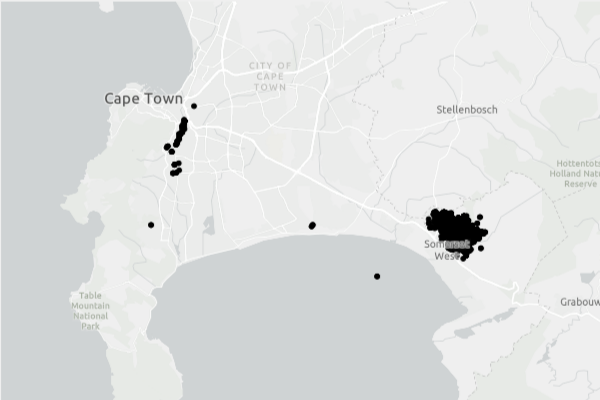

As if GSOB were not a sufficient threat to California’s oaks, several other non-native pests are already established in the state. These include at least seven pests and pathogens:

- sudden oak death pathogen;

- three shot hole borers — polyphagous, Kuroshio, and Euwallaceae interjectus; they attack at least Coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii), Valley oak (Quercus lobata), Canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis)

- Mediterranean oak borer; attacks valley oak (Quercus lobata); blue oak (Q. douglasii); and Oregon oak (Q. garryana).

- acute oak decline (bacterium Rahnellav victoriana);

- foamy bark canker (caused by Geosmithia pallida); and

- possibly two Diplodia fungi.

At least GSOB, SOD, and two of the shot hole borers have received official “zone of infestation” (ZOI) designation by the California Board of Forestry. This designation enables

- the Board to specify required pest mitigation measures for any timber harvest;

- the Board & the CalFire authority to enter private properties to abate pest problems if necessary.

- calls attention to the presence of the pest within the Zone and provides the Department with a talking point to motivate landowners & land managers to address problems caused by the pest in question.

The southern California coalition includes these other bioinvaders in its efforts.

Lobbying by members of the coalition – especially John Kabashima – resulted in the state legislature providing funds to address the invasive shot hole borers (see here and here.)

Summary of information in the brief

Tardy detections

Although oak decline was observed in eastern San Diego County as early as 2002, and a GSOB was caught in a survey trap in 2004, the beetle’s role in killing these oaks was identified only in 2008. This detection was followed by the discovery of disjunct infestations were detected in towns surrounded by National forests first in Riverside County (2012), then in Orange County (2014) and Los Angeles County (2015). Outbreaks in San Bernardino County were detected in 2018 – although the beetle had probably been present since 2013. The LA County populations continued to spread, despite management efforts. The obvious danger prompted neighboring Ventura County to initiate surveillance trapping in 2023. Sure enough, this sixth county found its first outbreaks in 2024. Most of the initial outbreaks have been on private land bordering or surrounded by National forests.

Responses: State, County, and Federal

The California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) classifies GSOB as a level “B” pest. Pests in this category are known to cause economic or environmental harm; however, their distribution is considered to be “limited”. Efforts to eradicate, contain, suppress, or control the species are at the discretion of individual county agricultural commissioners.

There is some outside support – usually because of the link to increased fire danger. Grants from the National Forest Foundation have enabled local Fire Safe councils, CalFire, and the Inland Empire Resource Conservation District (IERCD) to conduct surveys and in some cases removal of amplifier trees in Riverside and San Bernardino counties. However, the funds no longer support the earlier practice of spraying at-risk trees.

County-by-County

In Orange County, a coalition of academics from the University of California and scientists with CalFire and USFS are testing various pesticide applications and efficacy of removing heavily infested trees. The county has adopted an Early Detection Rapid Response Plan.

Since the first detection of GSOB in Los Angeles County in 2015, authorities have removed nearly 10,000 “amplifier” trees. Because the Santa Monica Mountains are home to 151,000 oaks, LA County Agricultural Commissioner of Weights and Measures, the Santa Monica Mountain Resource Conservation District (RCD), Los Angeles National Forest and UC Cooperative Extension established a joint “Bad Beetle Watch” program with Ventura County. The program is training agency personnel, tree professionals, and recreationists to detect GSOB. A state agency – Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority – is managing two outbreaks in the Santa Monica Mountains. The Los Angeles County Fire / Forestry Division is surveying the oak-dense San Fernando Valley and Santa Susana Mountains after GSOB was found nearby. The Los Angeles County Regional Planning agency will target oak-dense communities with advocacy for oak woodland health and warnings not to move firewood.

Most encouraging, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is considering declaring a local or state emergency related to the risk of the spread of GSOB in the County and to the Santa Monica Mountains.

Ventura County began trapping at green waste facilities and campgrounds in 2023. Now that GSOB has been detected, several agencies — CalFire, Ventura County Fire, Ventura County Resource Conservation District, California Coastal Conservancy, Rivers and Mountains Conservancy, Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, Ojai Valley Land Conservancy, Ventura Fire Safe Council, Ojai Valley Fire Safe Council as well as the state lands commission and Los Padres National Forest – are gearing up educational programs focused on the risk of GSOB spread to additional areas. The non-governmental organization Tree People helped to spark this effort. Efforts are under way to fund and formalize a regional coalition, with collaboration from California Department of Conservation, CAL FIRE, and UC Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Despite the damage to state parks and the clear nexus with firewood, the California State Park agency encourages – but does not require – campers and picnickers to purchase certified clean firewood on site from camp hosts.

Affected Tribal Lands

Among affected Native American reservations, the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians has already removed almost one thousand large coast live oak trees in the Tribe’s campground; another thousand trees must be removed in coming years. Since 2019, the Tribe has been applying contact insecticides annually on 200 to 300 trees. In addition, the Tribe is planting seedlings and conducting research in partnership with UC Riverside, San Diego State University, and UC Irvine. Obtaining funds to develop management capacity is a constant challenge.

A second tribe, the Pala Band of Mission Indians, began a systematic survey of its lands in 2022. At that time, they found a light infestation in coast live oaks and some dispersal. Hundreds of dead trees are visible from highways bordering the Mesa Grande, Santa Ysabel, and Los Coyotes reservations. Even reservations that have no oaks on their land are affected because tribal members harvest acorns as a culturally important food.

Private Reserves

Two private reserves in Orange County responded aggressively to arrival of GSOB. The Irvine Ranch Conservancy started active management immediately after detection of GSOB in 2014. Their efforts – annual surveys, treating lightly infested trees, and removing heavily infested or “amplifier” trees – have paid off: by 2023, only 21 of 187 coast live oaks surveyed had new exit holes – and in most cases only one or two. Weir Canyon is considered a successful control program.

Managers of the California Audubon Starr Ranch Sanctuary began monitoring for GSOB by 2016. No GSOB were detected until 2023. Difficult terrain impedes survey and response. Orange County Fire Authority hired contractors to remove amplifier trees and treat others. Monitoring continues.

Responses by Federal Agencies

The Angeles, Cleveland, and San Bernardino National forests all have extensive and evolving management plans for GSOB. Actions include annual surveys, tree removal and/or treatment, regulating concessionaires’ sources of firewood, and restricting wood harvest permits. Each forest has also partnered with appropriate counties, NGOs, FireSafe councils, and Resource Conservation districts to expand outreach, monitoring, and management. Many of the efforts are centered around communities within and adjacent to National Forest boundaries and recreation sites, since they are the main source of GSOB ingress. Success is not guaranteed. Six years of applying contact insecticides to high-visit recreation sites did not prevent establishment of at least two new infestations on private inholdings in Trabuco Canyon (Cleveland National Forest).

The fourth National Forest in southern California, Los Padres NF – which lies partially in Ventura and Los Angeles counties – has not yet found any GSOB but it is preparing. The Forest conducted a forest health training with heavy emphasis on GSOB in spring 2024 and is in the process of creating its own monitoring and management plan to include preemptive evaluation of environmental concerns under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) and planning.

GSOB management is an important facet of the National Forest Wildfire Crisis Strategy implemented by all four National Forests in southern California. Challenges include steep and inaccessible terrain; wilderness designations; designation of sensitive habitat for wildlife, ecological, or heritage sites; and the sheer amount of land managed. Despite this, the forests have expanded their efforts each year. At the National Plant Board meeting in July, Sky Stevens reported that GSOB is one of the priority pests being addressed by the Forest Health Protection program. However, this program has been severely downsized by the Trump Administration, so its ability to assist is unclear. Budgets for individual National forests are also in limbo.

The Issue of Firewood

Several National parks located in California contain important oak forests and woodlands that are also at risk, especially given the importance of firewood in spreading the pest. Yosemite and Kings Canyon-Sequoia National parks and other campgrounds in the Sierra Nevada receive large numbers of campers from the Los Angeles area.

A 2014 National Park Service resource guide for firewood management summarized federal plant pest regulations at the time. These have since changed because emerald ash borer is no longer federally regulated. The guidance advised Park staff to define their park’s forest resources, keep abreast of present and potential forest pest species, and act to manage risks from potentially infested firewood. Park concessioners are required to purchase and sell only locally grown and harvested firewood in accordance with state quarantines. However, California does not have relevant quarantines for either firewood as a commodity or for oak pests specifically. The websites of Yosemite and Kings Canyon-Sequoia National parks ask people not to bring firewood obtained from a source more than 50 miles from the parks.

California does participate in the Firewood Scout program, Firewoodscout.org which advises campers on local sources from which to purchase their wood. Statewide, a consortium of several agencies, academia, and non-government agencies operates a “Buy It Where You Burn It” campaign that promotes this message with the public and firewood vendors.

Funding is a perpetual problem. No agency, not even CalFire, is funded to remove amplifier trees. The agency does use its crews to remove GSOB infested trees when they can. Most funding for treating infested trees comes from competitive grants awarded by CalFire or National Forest Foundation.

In 2012 the California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection (which is appointed by the Governor) officially designated a Zone of Infestation (ZOI) for GSOB. The Zone has been expanded as the infestation spread. The Zone of Infestation formally recognizes GSOB as a threat to California’s woodland resources and seeks to raise awareness among the governor, legislature, and public. The action was also intended to foster collaborative efforts to manage the beetle.

Joelene Tamm, Vice Chair of the California Forest Pest Council Southern California Committee (CFPC), is leading an initiative to address wildfire risks from invasive pests, including GSOB, South American Palm Weevil, and the invasive shothole borers. She presented a pest update with potential solutions to the California Board of Forestry (BOF) and followed up with a presentation to the BOF Resource Protection Committee, which is now identifying responsive actions. The Governor’s Wildfire Task Force is considering incorporating the topic into future meetings. The initiative’s core message is that the state must address the root cause of pest proliferation, as treating the symptom of wildfire alone is an unsustainable strategy (Tamm, pers. comm. August 2025).

For more details and sources, visit the GSOB brief here.

[I could find no recent updates about a third Agrilus, the soapberry borer (Agrilus prionurus), which is established in Texas from Mexico and was earlier said to kill the western soapberry (Sapindus saponaria var drummondii). It is established in at least 42 counties, reaching from the Dallas-Ft. Worth area to the Rio Grande valley.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

Or