In this blog I describe one state’s forest health efforts – Virginia. The pertinent lesson is the importance of external funding, especially that provided by USFS Forest Health Protection program, in supporting states’ efforts. Is your state’s forest health program as dependent upon federal funding as Virginia’s is? If so, there is a role for everyone: lobby your Congressional representative and senators to increase funding for this program!

I have based most of this blog on the Virginia Department of Forestry’s annual report for 2022.

Forests grow on more than 16 million acres in Virginia, or 62% of the Commonwealth’s land area. Eighty percent of these forests are hardwood or hardwood-pine. They break down as follows: 61% oak-hickory; 11% oak-pine; 5% bottomland hardwood; and 2% maple-beech-birch. A fifth of the forest is pine, composed of pine plantation (14%) and natural pine (7%). The long term trend is growth, especially among hardwoods.

The report devotes much of its attention to the agency’s programs to advise private landowners (individuals own 80% of the Commonwealth’s forestland); fire management (including prescribed burns); and state and federal conservation programs (e.g., easements). A major program shares reforestation costs on harvested pine lands. In 2022, this program assisted reforestation practices on 74,702 acres. Virginia has an impressive tree-raising program. VDOF grows more than 40 species, including longleaf and shortleaf pine, several spruce species, and dozens of hardwoods. The aim is to provide stock suited for the Commonwealth’s soils and climate. Many of the hardwood species are grown from acorns and seeds collected and donated by volunteers.

VDOF also helps to protect and improve the Commonwealth’s water quality through tree planting and sound forest management. VDOF has an unusual responsibility: enforcing the Virginia Silvicultural Water Quality Law.

The report also summarizes several urban and community forestry programs focused on education, community engagement, tree selection, and grants for tree planting to ensure canopy retention & management.

Forest Health – Importance of Federal Funding

Slightly over 1 million acres was mapped by aerial surveys in FY22. I believe the funding for these surveys came largely from the USFS. The surveys detected heavy to moderate defoliation by the spongy moth on 24,493 acres (almost twice the area detected in FY21). The spongy moth infestation is primarily in counties on the western side of the state, in the mountainous region, which has the highest densities of oaks and other hardwoods.

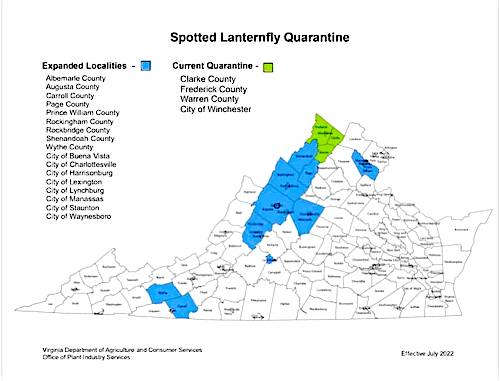

The spotted lanternfly (SLF) was detected in Virginia early – in 2018 in Winchester at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. Winchester is connected to central Pennsylvania by Interstate 81, so rapid movement of SLF to Virginia from outbreaks slightly to the east of I-81 in Pennsylvania doesn’t surprise me. SLF has been spreading south along the mountains and over the Blue Ridge to Loudoun and Fairfax counties (in 2022). Fairfax County has announced a four-year, $200,000 effort to try to slow SLF spread by eradicating high densities of its preferred host, Ailanthus, from two county parks in the far south and north ends of the county. Ailanthus removal requires not just cutting the trees, but applying herbicide to prevent sprouting from the roots. This work is funded by the county, the local park authority and a $20,000 grant from the regional energy company, Dominion Energy Charitable Foundation.

Virginia has six species of ash: white and green (both common), and smaller populations of black, blue, pumpkin and Carolina. EAB is now confirmed in 84 counties – most of the Commonwealth except the far southeast. The Department of Forestry treats 130 – 150 trees per year – half or more on state lands. At least in FY21, the funding came from federal sources. The report also notes outreach efforts at two minor league baseball games. Virginia recently adopted a priority of protecting the Chesapeake Bay watershed by promoting tree planting in riparian forest buffers. The EAB threatens this goal; see the photo (at top) of ash mortality along a Maryland tributary of the Bay. In 2021, EAB was detected in Gloucester County – a peninsula east of the York River that has Bay shoreline on the eastern side, tributary on the west (see photo).

Gloucester Point – Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences “living shoreline”; EAB was detected in Gloucester County in 2021, threatening riparian areas. Photo courtesy of the Chesapeake Bay Program

Threats to Beech

Beech bark disease is present in the western mountainous parts of the Commonwealth. One new county – Augusta – was detected in 2022. Three other counties are infested with the scale, but the fungal pathogen has not yet been detected. The alarming new threat, beech leaf disease, was detected in Prince William County in 2021. In 2022, it was confirmed in neighboring Fairfax County. The source of funding is not specified.

I am pleased that the Commonwealth is paying attention to laurel wilt disease, which has been spreading north on sassafras. The closest outbreaks are in Tennessee, to the southwest of Virginia. The Commonwealth hosted a detection training program attend by 26 participants from six agencies from three states. The report does not specify the source of the funding.

Southern Pine Beetle

Virginia has also utilized funding from the USFS FHP program to manage the southern pine beetle. Since the program’s inception in 2004, Virginia has thinned pines on more than 70,000 acres, including 4,240 acres in FY22.

Invasive Plants

USFS FHP invasive species grants funded control treatments of invasive plants on somewhat less than 1,300 acres of state lands. Different figures on different pages of the report cause confusion. However, it is clear that nearly all the funds came from the USFS FHP program. Ailanthus was the main target; other species mentioned are privet, mimosa, autumn olive and Miscanthus.

State Funding of Conservation Initiatives; Will They Continue?

While the state’s government was controlled by Democrats, the governor and state legislature launched new programs with broader conservation goals. It is unclear whether they will continue now that Republicans have won the governorship and control of the House of Delegates.

Among the programs enjoying increased funding from the state budget during the current two-year cycle are

- Efforts to restore depleted populations of two groups of tree taxa, shortleaf and longleaf pines. The emphasis has shifted to longleaf pine: the number of projects and acreages rose from 220 acres in FY21 to 1,212 acres in FY22. Restoration of shortleaf pine forests was limited to slightly over 600 acres in both years.

- Programs to improve management of hardwood stands. These projects included crop tree release, control of “invasive species” (I think probably targetting invasive plants), prescribed burning and commercial thinning. There were also several demonstration projects on state-owned lands, a small land-owner planning assistance program, and training of state foresters and private consulting foresters in hardwood management. Apparently these aspects had been largely ignored in the past.

- Creation of a dedicated Watershed program focused on increasing riparian forest buffers. This section of the report does not mention the threat posed by loss of ash to the emerald ash borer (EAB) [see EAB section above]

- Urban forestry projects, many linked to protecting surface and ground water (including Chesapeake Bay watershed).

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or

see also the article about beech leaf disease in the mid-Atlantic region written by Gabe Popkin; posted here