photo by Rick Kyper, US Fish and Wildlife Service

I expect you have heard about the report issued on May 6 by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. The executive summary is available here

Based on thousands of scientific studies, the report concludes that the biosphere, upon which humanity as a whole depends, is being altered to an unparalleled degree across all spatial scales. The trends of decline are accelerating. As many as 1 million species (75% of which are insects) are threatened with extinction, many within decades.

Humans dominate Earth: natural ecosystems have declined by 47% on average. Especially hard-hit are inland waters and freshwater ecosystems: only 13% of the wetland present in 1700 remained by 2000. Losses have continued rapidly since then.

The report lists the most important direct drivers of biodiversity decline – in descending order – as habitat loss due to changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of organisms; climate change; pollution; and invasive species. The relative importance of each driver varies across regions.

If you have been paying attention, these conclusions are not “news”.

However, the report serves two valuable purposes. First, it provides a global overview, a compilation of all the data and trends. Second, the report ties the direct drivers to underlying causes which are in turn underpinned by societal values and behaviors. Specifically mentioned are production and consumption patterns, human population dynamics and trends, trade, technological innovations, and governance (decision making at all levels, from local to global).

The report goes to great lengths to demonstrate that biological diversity and associated ecosystem services are vital for human existence and good quality of life – especially for supporting humanity’s ability to choose alternative approaches in the face of an uncertain future. The report concludes that while more food, energy and materials than ever before are now being supplied to people, future supplies are undermined by the impact of this production and consumption on Nature’s ability to provide.

The report also emphasizes that both the benefits and burdens associated with the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services are distributed and experienced inequitably among social groups, countries and regions. Furthermore, benefits provided to some people often come at the expense of other people, particularly the most vulnerable. However, there are also synergies – e.g., sustainable agricultural practices enhance soil quality, thereby improving productivity and other ecosystem functions and services such as carbon sequestration and water quality regulation.

The report contains vast amounts of data on the recent explosion of human numbers and – especially – consumption – of agricultural production, fish harvests, forest products, bioenergy production … and on the associated declines in “regulating” and “non-material contributions” ecosystem services. In consequence, the report concludes, these recent gains in material contributions are often not sustainable.

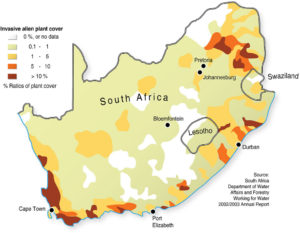

While invasive species rank fifth as a causal agent of biodiversity decline globally, alien species have increased by 40% since 1980, associated with increased trade and human population dynamics and trends. The authors report that nearly 20% of Earth’s surface is at risk of bioinvasion. The rate of invasive species introduction seems higher than ever and shows no signs of slowing.

The report notes that the extinction threat is especially severe in areas of high endemism. Invasive species play a more important role as an extinction agent in many such areas, especially islands. However, some bioinvaders also have devastating effects on mainlands; the report cites the threat of the pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis to nearly 400 amphibian species worldwide.

The report also mentions that the combination of species extinctions and transport of species to new ecosystems is resulting in biological communities – both managed and unmanaged — becoming more similar to each other — biotic homogenization.

The report notes that human-induced changes are creating conditions for fast biological evolution of species in all taxonomic groups. The authors recommend adopting conservation strategies designed to influence evolutionary trajectories so as to protect vulnerable species and reduce the impact of unwanted species (e.g., weeds, pests or pathogens).

The report says conservation efforts have yielded positive outcomes – but they have not been sufficient to stem the direct and indirect drivers of environmental deterioration. Since 1970, nations have adopted six treaties aimed at protection of nature and the environmental, but few of the strategic objectives and goals adopted by the treaties’ parties are being realized. One objective that is on track to partial achievement is the Aichi Biological Diversity Target that calls for identification and prioritization of invasive species.

That might well be true – but I would not consider global efforts to manage invasive species to be a success story in any way. I have blogged often about studies showing that introductions continue unabated … and management of established bioinvaders only rarely results in measurable improvements. [For example, see here and here.]

The report gives considerable attention to problems caused by some people’s simultaneous lack of access to material goods and bearing heavier burden from pollution and other negative results of biodiversity collapse. Extraction of living biomass (e.g. crops, fisheries) to meet the global demand is highest in developing countries whereas material consumption per capita is highest in developed countries. The report says that conservation of biodiversity must be closely linked to sustainable approaches to more equal economic development. The authors say both conservation and economic goals can be achieved – but this will require transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors.

One key transformation is changing people’s conception of a good life to downplay consumption and waste. Other attitudinal changes include emphasizing social norms promoting sustainability and personal responsibility for the environmental impacts of one’s consumption. Economic measures and goals need to address inequalities and integrate impacts currently considered to be “economic externalities”. The report also calls for inclusive forms of decision-making and promoting education about the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Economic instruments that promote damaging, unsustainable exploitation of biological resources (or their damage by pollution) include subsidies, financial transfers, subsidized credit, tax abatements, and commodity and industrial goods prices that hide environmental and social costs. These need to be changed.

Finally, limiting global warming to well below 2oC would have multiple co-benefits for protecting biodiversity and ecosystem services. Care must be exercised to ensure that large-scale land-based climate mitigation measures, e.g., allocating conservation lands to bioenergy crops, planting of monocultures, hydroelectric dams) do not themselves cause serious damage to biodiversity or other ecosystem services.

The threats to biodiversity and ecosystem services are most urgent in South America, Africa and parts of Asia. North America and Europe are expected to have low conversion to crops and continued reforestation.

Table SPM.1 lays out a long set of approaches to achieve sustainability and possible actions and pathways for achieving them. The list is not exhaustive, but rather illustrative, using examples from the report.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.