Prompted by the rising number of Phytophthora-caused diseases in forests on several continents, in 1999 the International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) formed the IUFRO Working Party 7.02.09 ‘Phytophthora Diseases of Forest Trees’. Last spring This group published a global overview of Phytophthora diseases of trees (Jung et al. 2018; see full citation at the end of this blog).

The study covers 13 different outbreaks of Phytophthora-caused disease in forests and natural ecosystems of Europe, Australia and the Americas.

The picture is alarming!

Jung et al. state definitively that the international movement of infested nursery stock and planting of reforestation stock from infested nurseries have been the main pathway of introduction and establishment of Phytophthora species in these forests.

The Picture: A Growing List of Diseases, Species, and Places Affected,

Jung et al. note that, during the past six decades, the number of previously unknown Phytophthora declines and diebacks of natural and semi-natural forests and woodlands has increased exponentially. The vast majority of these disease complexes have been driven by introduced invasive Phytophthora species. In 1996, 50 Phytophthora species were known. In the 20 years since then, more than 100 new Phytophthora species have been described or informally designated. One study (Tsao 1990) estimated that more than 66 % of all fine root diseases and more than 90 % of all collar rots of woody plants are caused by Phytophthora spp. Many of these had previously been attributed to abiotic factors or secondary pathogens. One example – surprising to me, at least – is that decline of mature beech trees in Central Europe is linked to Phytophthora rather than beech bark disease!

Several of the disease complexes described in Jung et al. 2018 are causing heartrending destruction of unique floras, e.g., jarrah, tuart, and other communities of western Australia and kauri forests of New Zealand. The authors expect increasing damage to the Mediterranean maquis in the future. They list these among other examples:

- Ink disease of chestnuts worldwide

- Oak declines and diebacks in Europe and North America

- Decline and mortality of alders (Alnus species) in Europe

- Decline and mortality of Port-Orford cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana) in Europe and North America

- Kauri dieback in New Zealand link to earlier blog

- Decline and mortality of Austrocedrus chilensis and Juniperus communis in Argentina and Europe

- Diebacks of natural ecosystems in Australia

- Decline and dieback of the Mediterranean maquis vegetation

- Decline and dieback of European beech in Europe and the US

- Dieback and mortality of southern beech (Nothofagus species) in the United Kingdom and Chile

- ‘Sudden Oak Death’ and ‘Sudden Larch Death’ in the US and United Kingdom

- Leaf and twig blight of holly (Ilex aquifolium) in Europe and North America

- Needle cast and defoliation of Pinus radiata in Chile

Several of the Phytophthoras are causing severe damage on several continents:

- P. cinnamomi in Europe, North America, and Australia

- P. austrocedri in South America, Europe, and western Asia

- P. ramorum in Europe and North America

- P. lateralis in North America and Europe.

Often, the genetic makeup of the Phytophtoras species varies in these different locations. These differences indicate separate introductions and the existence of sexual reproduction and continuing evolution in response to conditions.

Why Phytophthoras are Spreading via the Plant Trade and Nursery Practices

First, Phytophthora species are able to survive unsuitable environmental conditions over several years as dormant resting structures in the soil or in infected plant tissues. When environmental conditions become suitable, the resting spores germinate – often prolifically. Since visible symptoms might not appear for considerable time after infection because the mechanism is progressive destruction of the fine root system, detection of the disease is delayed, further undermining control.

Second, most of the Phytophthora species causing disease complexes were unnoticed as co-evolved species in their native environment. Often they were unknown to science before their introduction to other continents – where they become invasive on naïve plant species. Consequently, these species are not captured by the international plant health system, which is based on lists of recognized “pest” species.

Third, the common nursery practice of applying fungicides or fungistatic chemicals masks the presence of pathogens – another way plants pass unnoticed through phytosanitary controls. These chemicals do not, however, kill the pathogen.

Fourth, the importation into receiving nurseries of plants from around the world provides ample opportunity for the introduced Phytophthoras to hybridize. The interspecific hybrids may differ in host range and virulence from the parent species, thus making predictions about the potential effects of an ongoing invasion even more difficult.

Fifth, the nurseries or plantings in gardens or restoration projects also provide suitable environments for prolific germination and spread.

All of these risks were first enumerated by the eminent British pathologist Clive Brasier a decade ago! (See Brasier et al. 2008 citation at the end of the blog.)

As Jung et al. 2018 point out, the scientific community has repeatedly urged regulators to require the use of preventative system approaches for producing Phytophthora-free nursery stock (see references in the article). Scientists have provided research-based guidance to reduce the risk of infestation. Such measures are being implemented by only some nurseries in the US. For example, USDA APHIS has specific requirements for nurseries that ship hosts of P. ramorum in interstate commerce after the nurseries or the plants have tested positive. More broadly, APHIS, the states, and the nursery industry are in the second round of pilot testing of an integrated measures approach to managing all pests under the Systems Approach to Nursery Certification (SANC) program

At the international level, the International Plant Protection Convention has adopted ISPM#36, which also envisions greater reliance on systems approaches. However, the preponderance of international efforts to protect plant health continue to rely on visual inspections that look for species on a list of those known to be harmful. Yet we know that most damaging Phytophthoras were unknown before their introduction to naïve ecosystems.

Furthermore, use of fungicides and fungistatic chemicals is still allowed before shipment.

As pointed out by several experts beginning with Dr. Brasier but including Liebhold et al. 2012, Santini et al. 2013, Jung et al. 2016, Eschen et al. 2017, this approach has failed to halt spread of highly damaging pathogens. (I note that the list of such pathogens is not limited to Phytophthoras; see the description of ohia rust in Hawai`i, Australia, and New Zealand).

Jung et al. 2018 also call for increasing the genetic resistance of susceptible tree species. The authors regard this as the most promising sustainable management approach for stabilizing declining natural ecosystems and for reintroducing susceptible tree species at sites with high disease impact. See my blogs about efforts to enhance U.S. tree-breeding posted earlier this year.

SOURCES

Brasier CM. 2008. The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathology 57: 792–808.

Jung T, Orlikowski L, Henricot B, et al. 2016. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora diseases. Forest Pathology 46: 134–163.

Jung, T., A. Pérez-Sierra, A. Durán, M. Horta Jung, Y. Balci, B. Scanu. 2018. Canker and decline diseases caused by soil- and airborne Phytophthora species in forests and woodlands. Persoonia 40, 2018: 182–220 Open Access!

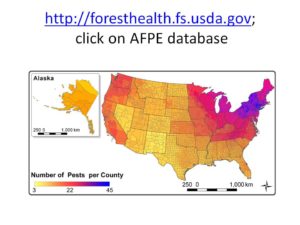

Liebhold AM, Brockerhoff EG, Garrett LJ, et al. 2012. Live plant imports: the major pathway for forest insect and pathogen invasions of the US. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment 10: 135–143.

Santini A, Ghelardini L, De Pace C, et al. 2013. Biogeographic patterns and determinants of invasion by alien forest pathogens in Europe. New Phytologist 197: 238–250.

Tsao PH. 1990. Why many Phytophthora root rots and crown rots of tree and horticultural crops remain undetected. Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin 20: 11–17

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Ailanthus altissima

Ailanthus altissima

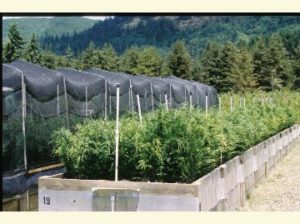

Port-Orford cedar resistance trials

Port-Orford cedar resistance trials