removing Miconia from Hawaiian forest; courtesy of the Nature Conservancy of Hawai`i

A recent article by Wayne Dawson and 24 coauthors (see reference at the end of this blog) provides the first-ever global analysis of established alien species. They studied the diversity of established alien species belonging go eight taxonomic groups – amphibians, ants, birds, freshwater fish, mammals, reptiles, spiders and vascular plants – across 609 regions (186 islands or archipelagos, and 423 mainland regions).

The analysis found that the highest numbers of established alien species in these taxonomic groups were in the Hawaiian Islands, New Zealand’s North Island and the Lesser Sunda Islands of Indonesia. The Hawaiian Islands have high numbers of invasive species in all of the eight groups studied. In New Zealand, the highest numbers were invasive plants and introduced mammals that prey on the native birds.

Florida is the top hotspot among mainland regions. Florida is followed by the California coast and northern Australia.

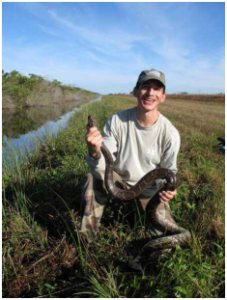

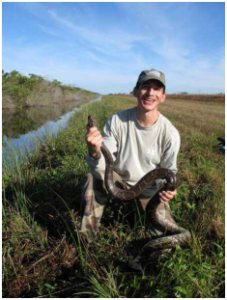

Burmese python in the Florida Everglades; photo by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Patterns

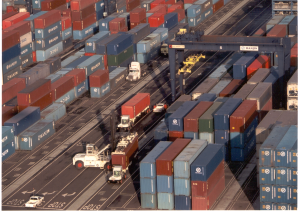

Invasive species hotspots were found mainly on islands and in coastal regions of mainland areas. The lead author, Dr. Wayne Dawson, a researcher at Durham University’s Department of Biosciences, suggested that the greater invasive species richness in coastal regions probably results from higher rates of species introductions to port areas compared to interior regions.

Island regions have, on average, higher cross-taxon invasive species richness. This cross-taxon richness on islands tends to be higher for those islands further from continental landmasses. The authors suggest that such oceanic islands might be more likely to import large quantities of goods from foreign sources than islands close to continents, thus experiencing higher propagule pressure.

Associations

Regions with greater wealth (measured as per capita GNP), human population density, and area have higher established alien richness. These effects were strongest on islands. The authors suggest that wealth and human population density might correlate with higher numbers of species being brought to the region through trade and transport.

On mainlands, cooler regions have higher richness. I think this might reflect history – centuries of colonial powers importing plants and animals. However, colonial powers also introduced species to tropical regions. In contrast, on islands warmer and wetter regions have higher richness of invasive species.

Drivers

The authors conclude that cumulative numbers of invasive species at a particular location are driven to a greater extent by differences in area and propagule pressure than by climate. The model that best explains cross-taxon invasive species richness combines per capita GDP, population density and sampling effort. Other important factors are area of the region, mean annual precipitation, and whether a region is on a mainland or island(s).

The study results show that, per unit increase in area, per capita GDP, and population density, invasive species richness increases at a faster rate on islands than on mainlands. This might be confirmation of the longstanding belief that islands are more readily invaded than mainlands, although the authors caution that a rigorous test of this explanation would require data on failed introductions.

The authors call for additional research to understand whether these effects arise because more species are introduced to hotspot regions, or because human disturbance in these regions makes it easier for the newcomers to find vacant spaces and opportunities to thrive.

I think it would be helpful to compare the findings on invasive species richness in specific regions to data on historic patterns of trade and colonization to strengthen our understanding of the importance of propagule pressure in determining invasion patterns.

Increasing Confirmation of Significance and Breadth of Invasive Species Threat

The Dawson et al. study is the latest in a series of analyses of global or regional patterns in invasive species. I have blogged previously about several of these:

- Bradshaw et al. 2016 concluded that invasive insects alone cause at least $77 billion in damage every year, a figure they described as a “gross underestimate”.

- A study by Hanno Seebens and 44 coauthors showed that the rate of new introductions of alien species has risen rapidly since about 1800 – and shows no sign of slowing down. Adoption of national and international biosecurity measures have been only partially effective, failing to slow deliberate introductions of vascular plant species, birds, and reptiles, and accidentally introduced invertebrates and pathogens. Like Dawson et al, Seebens et al. found a strong correlation between the spread of bioinvaders introduced primarily accidentally as stowaways on transport vectors or contaminants of commodities (e.g., algae, insects, crustaceans, molluscs and other invertebrates) and the market value of goods imported into the region of interest.

- Liebhold et al. 2016(see reference below) studied insect assemblages in 20 regions around the world. They found that an insect taxon’s ability to take advantage of particular invasion pathways better explained the insect’s invasion history than the insects’ life-history traits. (The latter affect the insect’s ability to establish in a new ecosystem.)

- Maartje J. Klapwijk and several colleagues note that growing trade in living plants and wood products has brought a rise in non-native tree pests becoming established in Europe. The number of alien invertebrate species has increased two-fold since 1950; the number of fungal species has increased four-fold since 1900.

- Jung et al. (2015) studied the presence of Phytophthora pathogens in nurseries in Europe. They found 59 putatively alien Phytophthora taxa in the nurseries. Two-thirds were unknown to science before 1990. None had been intercepted at European ports of entry when they were introduced. Nor have strict quarantine regulations halted spread of the quarantine organism ramorum.

- A report by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) on World Heritage sites globally found that invasive species were second to poaching as a threat to the sites’ natural values. Of 229 natural World Heritage sites examined, 104 were affected by invasive species. Island sites – especially in the tropics – were most heavily impacted.

- Another report by IUCN found that invasive species were the second most common cause of species extinctions – especially for vertebrates.

Conclusions

These studies demonstrate that

- Invasive species have become a significant threat to biological diversity and ecosystem services around the world – one that continues to grow.

- The recent spate of studies originating in Europe probably reflects recent recognition of the continent’s vulnerability – as seen, inter alia, in the proliferation of tree-killing Phytophthoras.

- Human movement of species – propagule pressure – whether deliberately or due to inadequate efforts to manage trade-related pathways – explain the bulk of “successful” introductions.

- Economic activity drives introductions, so areas at highest immediate risk are urban areas and other centers receiving high volumes of imports and visitors. Among troubling trends in the future is rapid global urbanization – along with rising economic interdependency.

- Efforts to curb these movements – at the national, regional, and international levels – have failed so far to counter the threat posed by invasive species of nearly all taxonomic groups.

In my view, the requirements that phytosanitary measures “balance” pest prevention against trade facilitation results in half measures being applied – and half measures achieve halfway results. For example, the U.S. does not require that packaging be made from materials that cannot transport tree-killing pests. The USDA has moved far too slowly to limit imports of plant taxa that pose a risk of either being invasive themselves or of transporting pests known to be damaging.

Conservationists should focus on building political pressure to strengthen regulations and other programs intended to curtail this movement. No other approach will succeed.

Sources

Bradshaw, C.J.A. et al. Massive yet grossly underestimated global costs of invasive insects. Nat. Commun. 7, 12986 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12986 (2016). (Open access)

Dawson, W., D. Moser, M. van Kleunen, H. Kreft, J. Perg, P. Pyšek, P. Weigelt, M. Winter, B. Lenzner, T.M. Blackburn, E.E. Dyer, P. Cassey, S.L. Scrivens, E.P. Economo, B. Guénard, C. Capinha, H. Seebens, P. García-Díaz, W. Nentwig, E. García-Berthou, C. Casal, N.E. Mandrak, P. Fuller, C. Meyer and F. Ess. 2017. Global hotspots and correlates of IAS richness across taxon groups. Nature Ecology and Evolution Vol. 1, Article 0186. DOI: 10.1038/s41559-017-0186 | www.nature.com/natecolevol

Jung,T., L. Orlikowski, B. Henricot, P. Abad-Campos, A.G. Aday, O. Aguin Casa, J. Bakonyi, S.O. Cacciola, T. Cech, D. Chavarriaga, T. Corcobado, A. Cravador, T. Decourcelle, G. Denton, S. Diamandis, H.T. Doggmus-Lehtijarvi, A. Franceschini, B. Ginetti, M. Glavendekic, J. Hantula, G. Hartmann, M. Herrero, D. Ivic, M. Horta Jung, A. Lilja, N. Keca, V. Kramarets, A. Lyubenova, H. Machado, G. Magnano di San Lio, P.J. Mansilla Vazquez, B. Marais, I. Matsiakh, I. Milenkovic, S. Moricca, Z.A. Nagy, J. Nechwatal, C. Olsson, T. Oszako, A. Pane, E.J. Paplomatas, C. Pintos Varela, S. Prospero, C. Rial Martinez, D. Rigling, C. Robin, A. Rytkonen, M.E. Sanchez, B. Scanu, A. Schlenzig, J. Schumacher, S. Slavov, A. Solla, E. Sousa, J. Stenlid, V. Talgø, Z. Tomic, P. Tsopelas, A. Vannini, A.M. Vettraino, M. Wenneker, S. Woodward and A. Perez-Sierra. 2015. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora disease. Forest Pathology.

Klapwijk, M.J., A.J.M. Hopkins, L. Eriksson, M. Pettersson, M. Schroeder, A. Lindelo¨w, J. Ro¨nnberg, E.C.H. Keskitalo, M. Kenis. 2016. Reducing the risk of invasive forest pests and pathogens: Combining legislation, targeted management and public awareness. Ambio 2016, 45(Suppl. 2):S223–S234 DOI 10.1007/s13280-015-0748-3 [http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms14435 ]

Liebhold, A.M., T. Yamanaka, A. Roques, S. Augustin, S.L. Chown, E.G. Brockerhoff, P. Pysek. 2016. Global compositional variation among native and nonindigenous regional insect assemblages emphasizes the importance of pathways. Biological Invasions (2016) 18:893–905

Seebens, H. et al., 2017. No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nature Communications. January 2017. [http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms14435 ]

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Posted by Faith Campbell

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org

F.T. Campbell dead sweetbay, Florida Everglades

F.T. Campbell dead sweetbay, Florida Everglades

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission