We have known since Darwin that oceanic islands can be cradles of speciation & endemism. Hawai`i exemplifies the phenomenon. Ninety-eight percent of native flowering plants are endemic (Cox). The density of native insect species in Hawai`i is higher than on mainland North America (Yamanaka).

We have known since Elton or earlier that oceanic islands are highly vulnerable to bioinvasion because their unique species did not evolve defenses against predation, herbivory, competition, or diseases; or the ability to adapt to changed soil chemistry or increased fire frequency.

Chapter 8 of the Office of Technology Assessment study of harmful invasive species states:

“Hawaii has a unique indigenous biota, the result of its remote location, topography, and climate. Many of its species, however, are already lost, and at least one-half of the wild species in Hawaii today are non-indigenous. New species have played a significant role in the extinction of indigenous species in the past and continue to do so. Hawaii, the Nation, and the world would lose something valuable as the indigenous fauna and flora decline.”

I apologize for not addressing the disasters wreaked on Hawai’i’s fauna and non-arboreal flora by invasive mammals and birds, plants, and such animal diseases as avian malaria and avian pox. For more on these topics, see the other sources listed below and the websites maintained by the Hawai`i Invasive Species Council and Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species. Cox notes that alien species span all trophic groups and threaten the complete replacement of the native terrestrial biota.

Outside of land clearing for ranches and other uses, much of the damage to Hawaii’s native forest trees has been caused by introduced mammals – especially pigs and goats; and invasive plants. Few of the enormous number of non-native insects that have established in Hawai`i appear to have attacked native trees. More than 2,600 non-native insects have been introduced; their number equals three-quarters of the NIS insects established in North America, yet Hawai`i constitutes less than 0.01% of the area of North America. The ratio of non-native to native insect species is higher for Hawai`i than for the other geographic areas studied by Yamanaka and colleagues (mainland North America, “mainland” Japan, and two offshore Japanese islands) (Yamanaka).

More than 13% of the non-native insects (=~350) in Hawai`i were introduced intentionally for biological control of agricultural pests and non-native plants (Yamanaka). Cox, Elton, and the Office of Technology Assessment discuss briefly the sometimes damaging effects of these deliberate introductions.

I am aware of only one NIS insect that has seriously threatened a native tree species: the Erythrina gall wasp, which killed many native wiliwili trees as well as lots of introduced coral trees planted in towns and as windbreaks. Biocontrol agents have helped prevent continuing damage from the gall wasp.

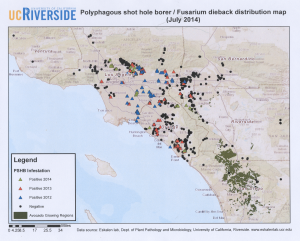

Disease pathogens have so far proved greater threats to Hawaiian native trees than introduced insects. Koa wilt is killing koa, especially at lower elevations. It is not certain whether the pathogenic Fusarium fungus is introduced or native; it has been found on all four major islands. Koa is second only to `ohi`a (see below) in abundance in mid to upper elevation Hawaiian forests. It is extremely important ecologically and culturally (koa was the tree from which large, ocean-going canoes were made). Koa also has a wood valued for a range of uses.

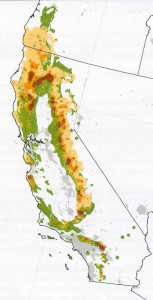

`Ohi`a lehua is the most widespread tree on the Islands, dominating approximately 80% of Hawai`i’s remaining native forest (about 965,000 acres, 1500 square miles). These forests are home to Hawai`i’s one native mammal (Hawaiian hoary bat) and 30 species of forest birds (Loope and LaRosa). One threat to `ohi`a comes from `ohi`a or eucalyptus rust. Detected in April 2005, it had spread to all the major islands by August. Fortunately, the strain of `ohi`a rust established in Hawai`i is not very virulent on `ohi`a, but it has killed many plants of an endangered native shrub, Eugenia koolauensis and in Australia it has killed many plants in the Myrtaceae family. Hawaiian conservationists worry that a different, more virulent, strain might be introduced on plants or cut foliage shipped to the Islands from either foreign sources or the U.S. mainland.

A new, apparently more damaging, pathogen was detected in 2010. This new disease is caused by two newly discovered species of the fungal genus Ceratocystis — Ceratocystis lukuohia and C. huliohia. By October 2015 the disease has killed 50% of the `ohi`a trees in several scattered locations totaling 6,000 acres on the southeast lowlands of Hawai`i (the “Big Island”). Tree mortality was nearing the boundary of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Hawaii Volcanoes pioneered methods for controlling invasive pigs and plants that threatened to destroy the Park’s forests. Through 40 years of sustained effort, Hawaii Volcanoes has brought those threats under control. Now the Park faces loss of its invaluable `ohi`a forest to this pathogen – which will be infinitely harder to keep out of the Park. (For updates on “rapid ohia death” visit the write-up here.)

The Hawai`i Department of Agriculture has adopted an emergency regulation aimed at preventing transport of infected wood or tree parts from the Big Island to other islands.

Although tree-killing insects and pathogens have so far not been as damaging in Hawai`i as might be expected, the Islands are highly vulnerable due to the large volumes of cargo and people from around the globe which land on the Islands and the few tree species native there. The Erythrina gall wasp has island-hopped from the east coast of Africa to Hawai`i and many islands in between. `Ohi`a rust is native to tropical America and probably reached the islands on cut stems used in floral decorations. It is unknown where the Ceratocytis fimbriata strain evolved or how it reached Hawai`i.

USDA APHIS is responsible for preventing introduction of new plant pests to Hawai`i from non-U.S. jurisdictions (as well as from Guam). APHIS has traditionally paid little attention to plant pests that are thought likely to threaten “only” Hawai`i but not plant (agricultural) resources on the mainland.

Hawaiian authorities are responsible for preventing introductions from the Mainland – but they struggle with inadequate resources to address the huge volumes of incoming freight and they sometimes hesitate to act. (Hawai`i Department of Agriculture considered restricting shipments of foliage in the Myrtacea to minimize the risk of introduction of a new strain of `ohi`a rust, but in the end did not adopt such a measure.)

Hawai`i’s unique biota is an irreplaceable treasure. All Americans should act to prevent introduction additional introductions to the Islands.

SOURCES:

Cox, George W. Alien Species in North America and Hawaii Impacts on Natural Ecosystems 1999

Elton, Charles S. The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants 1958; see especially Chapter 4: The Fate of Remote Islands

Loope, L. and LaRosa, A.M. `Ohi`a Rust (Eucalyptus Rust) (Puccinia psidii Winter) Risk Assessment for Hawai`i

U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment. 1993. Harmful Non-Indigenous Species In the United States. OTA-F-565; available at http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/ota/Ota_1/DATA/1993/9325.PDF

Yamanaka, T., N. Morimoto, G.M. Nishida, K. Kiritani, S. Moriya, A.M. Liebhold. 2015. Comparison of insect invasions in North America, Japan and their Islands. Biol Invasions DOI 10.1007/s10530-015-0935-y

Posted by Faith Campbell

![CBP agriculture specialists in Laredo, Texas, examine a wooden pallet for signs of insect infestation. [Note presence of an apparent ISPM stamp on the side of the pallet] Photo by Rick Pauza](http://nivemnic.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/CPB-SWPM-inspection-300x200.jpg)