(The total cost will exceed $36 billion – which will be borne largely by homeowners and municipalities – meaning their taxpayers. The state will bear little of this cost.)

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission

(To see more scary photos of the damage along the Tijuana River taken by John Boland, go here.

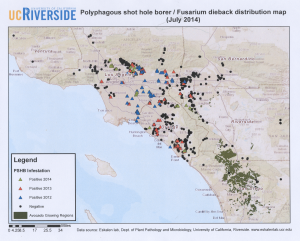

The polyphagous (PSHB) and Kuroshio (KSHB) shot hole borers pose a great threat to many tree species in California – native species in natural and urban settings; non-native species used in plantings; and agricultural crops. Yet the state government is frozen in inaction.

These two shot hole borers attack hundreds of tree species; at least 40 are reproductive hosts. For details, view the write-up here or visit the UC Riverside website here.

Some of the important reproductive hosts for PSHB are listed here; those that are also known to support reproduction of the Kuroshio shot hole borer are marked by an asterisk.

- Box elder (Acer negundo)

- Big leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) *

- California sycamore (Platanus racemosa)

- Several willows (Salix spp.)

- Cottonwoods (Populus fremontii & P. trichocarpa)

- Several oaks (Quercus agrifolia, Q. engelmannii, Q. lobata)

Several widespread exotic species also support PSHB reproduction: they include the invasive castor bean (Ricinus communis) and widely-planted London plane tree (Platanus x acerifolia).

US Forest Service scientist Greg McPherson has analyzed the vulnerability to PSHB of urban forests in cities in three regions of southern California: the Inland Empire, Coastal Southern California, and Southwest Desert. Together, these comprise 4,244 sq. miles and have 20.5 million residents. Dr. McPherson found that:

1) Approximately 26.8 million trees – 37.8% of the region’s 70.8 million trees – are at risk. Trees at risk include

- 5 million coast live oaks,

- 4 million ash,

- 3 million sycamores and plane trees,

- 9 million stone fruit or flowering Prunus species,

- 5 million avocadoes, and

- 8 million citrus trees.

2) The cost for removing and replacing the 26.8 million trees would be approximately $36.2 billion. This amount averages to $1,768 per capita.

3) The value of ecosystem services forgone each year due to the loss of these trees is $1.4 billion.

4) These estimates are conservative because they:

- do not include costs associated with damage to people and property from tree failures, as well as increased risk of fire and other hazards

- may undervalue benefits of trees to human health and well-being; and

- do not include newly detected host species or the shot borers’ spread.

These disasters are highly likely to occur given the extent of current infestations and difficulty in curtailing spread of the beetle/fungus complex.

Natural areas – especially riparian areas – are also at risk. John Boland reports that 70% of willows studied in the Tijuana River riparian area on the California/Mexico border were infested by KSHB. Tree branches and boles weakened by beetle attack broke in the first winter storms in early 2016. In some sections, “native riparian forest … went from a dense stand of tall willows to a jumble of broken limbs in just a few months.” Trees growing in the wettest parts of the riparian area were most heavily attacked and damaged. Three highly invasive plant species – castor bean, salt cedar, and giant reed – are barely or not attacked by KSHB. The result of the damage to native willows and likely proliferation of the invasive plants is likely to be significant alteration of the entire biological system.

(While no one knows how KSHB reached the Tijuana River, John Boland says there is a greenwaste “recycling” center in the valley. See picture below, taken by John Boland.)

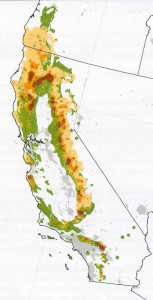

Regulatory action could help protect wildland, rural, and urban forests in the rest of the state – and possibly beyond. Scientists’ analysis of climate indicates that most of the urban and agricultural areas in California are at risk. The scientists have also begun analyzing the potential risk to other parts of country.

Why is the California government so unwilling to tackle a threat of this magnitude?

I have written about this inaction several times as it applies to the goldspotted oak borer. See my blogs on 1) California’s inaction on firewood in July 2015; 2) GSOB and firewood in September 2015; 3) contrasting states’ action on mussels with inaction on firewood posted in December 2015; and 4) the threats to oaks, posted in April 2016.

In October CISP joined an eminent forest entomologist, Dr. David Wood of the Department of Natural Resources at the University of California, Berkeley. We petitioned the California Department of Food and Agriculture to regulate movement of firewood within the state. CDFA refused, saying that the absence of control points through which firewood could be funneled made efforts to regulate its movements impractical. (For copies of our letter and CDFA’s reply, contact me through the “contact” button on the CISP website.)

While there are many questions about practical aspects of implementing and enforcing such regulations, I do not believe they are insurmountable.

I concede that CDFA has provided significant funds for firewood outreach campaigns. But people care about the threat posed by these pests and want CDFA to act. In the meantime, concerned people have formed formal partnerships linking local, county, state, and federal officials and academics to coordinate efforts to manage both GSOB and the PSHB and KSHB. Groups’ efforts can be viewed here and here. CalFire and the California Fire Wood Task Force are active participants.

During a recent conference call sponsored by the California Agricultural Commissioners and Sealers Association’ Pest Prevention Committee, participants reinforced the damaging consequences of CDFA’s inaction:

- While scientists are developing new tools for detection of the polyphagous and Kuroshio beetles and the fungi, there are no funds to support their use in a more intensive detection trapping effort!!!!! Call participants discussed various potential funding sources (e.g., from competitive grant programs operated by various agencies). Some survey efforts have been funded – by USDA APHIS:

- UC Riverside Professor Richard Stouthamer received Farm Bill §10007 funds for two years to develop traps and lures for PSHB.

- CDFA participates in a national woodborer survey which is funded by APHIS.

- In the absence of CDFA designation of PSHB, KSHB, or GSOB as regulated pests, neither state nor county agencies have a firm foundation on which to base regulations to curtail movement of firewood, greenwaste, or other pathways by which these pests can be spread to new areas.

It is clear from the discussion during the call that many people understand the need for regulations to ban movement of firewood out of southern California. But so far they have not succeeded in building sufficient political support to bring this about.

Meanwhile, other federal agencies are beginning to perceive the risk posed by these pests – and are struggling to develop responses. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is trying to develop strategies to protect the forested wetlands, which are habitats for the endangered least Bell’s vireo (a bird) and other endangered species. However, the USFWS lacks funds to carry forward desired detection and other programs. The USFWS offices in California are trying to engage agency leadership on this threat. So far, Endangered Species Act §7 requirements have not restricted removal of infested trees in wetlands already invaded by PSHB or KSHB.

Santa Monica National Recreation Area is the first National Park Service unit to pay attention. I have written in the past that the National Park Service should adopt a nation-wide policy banning visitors from bringing their own firewood to campgrounds (see my blogs from August and October 2015). In the absence of a nation-wide policy, action by individual units is important.

The USDA Forest Service is already engaged, especially with detection and outreach. However, the USFS also does not have nation-wide policy restricting campers from taking their own firewood to campgrounds on National forests.

Many Californians are pushing for action … they need our help! If you live in California, contact your state legislators. If you live elsewhere, your forests are also at risk from the state’s failure to act. So, if you know someone who lives there, ask that person to contact his/her legislators. Ask the legislators to demand state designation of PSHB, KSHB, and GSOB as quarantine pests and adoption of state firewood regulations.

SOURCE:

Memorandum from Greg McPherson, USDA Forest Service, to John Kabashima Re: Potential Impact of PSHB and FD on Urban Trees in Southern California, April 26, 2016

Posted by Faith Campbell