In summer 2019 I posted several blogs summarizing my analysis of forest pest issues after 30 years’ engagement. I reported the continuing introductions of tree-killing insects and pathogens; their relentless spread and exacerbated impacts. I noted the continued low priority given these issues in agencies tasked with preventing and solving these problems. Also, Congress provides not only insufficiently protective policies but also way too little funding. I decried the impediments created by several Administrations; anti-regulatory ideology and USDA’s emphasis on “collaborating” with “clients” rather than imposing requirements.

In my blogs, I called for renewed effort to find more effective strategies – as I had earlier advocated in my “Fading Forests” reports (link provided at the end of this blog), previous blogs, and Lovett et al. 2016

Areas of Progress

Now two years have passed. I see five areas of progress – which give me some hope.

1) Important Activities Are Better Funded than I had realized

a) The US Forest Service is putting significant effort into breeding trees resistant to the relevant pests, more than I had realized. Examples include elms and several conifer species in the West – here and here.

b) USDA has provided at least $110 million since FY2009 to fund forest pest research, control, and outreach under the auspices of the Plant Pest and Disease Disaster Prevention Program (§10201 of the Farm Bill). This total does not include additional funding for the spotted lanternfly. Funded projects, inter alia: explored biocontrol agents for Asian longhorned beetle and emerald ash borer; supported research at NORS-DUC on sudden oak death; monitored and managed red palm weevil and coconut rhinoceros beetle; and detected Asian defoliators. Clearly, many of these projects have increased scientific understanding and promoted public compliance and assistance in pest detection and management.

This section of the Farm Bill also provided $3.9 million to counter cactus pests – $2.7 million over 10 years targetting the Cactoblastis moth & here and $1.2 million over four years targetting the Harissia cactus mealybug and here.

2) Additional publications have documented pests’ impacts – although I remain doubtful that they have increased decision-makers’ willingness to prioritize forest pests. Among these publications are the huge overview of invasive species published last spring (Poland et al.) and the regional overview of pests and invasive plants in the West (Barrett et al.).

3) There have been new efforts to improve prediction of various pests’ probable virulence (see recent blogs and here.

4) Attention is growing to the importance of protecting forest health as a vital tool in combatting climate change — see Fei et al., Quirion et al., and IUCN. We will have to wait to see whether this approach will succeed in raising the priority given to non-native pests by decision-makers and influential stakeholders.

5) Some politicians are responding to forest pest crises – In the US House, Peter Welch (D-VT) is the lead sponsor of H.R. 1389. He has been joined – so far – by eight cosponsors — Rep. Kuster (D-NH), Pappas (D-NH), Stefanik (R-NY), Fitzpatrick (R-PA), Thompson (D-CA), Ross (D-NC), Pingree (D-ME), and Delgado (D-NY). This bill would fund research into, and application of, host resistance! Also, it would make APHIS’ access to emergency funds easier. Furthermore, it calls for a study of ways to raise forest pests’ priority – thus partially responding to the proposal by me and others (Bonello et al. 2020; full reference at end of blog) to create federal Centers for Forest Pest Control and Prevention.

This year the Congress will begin work on the next Farm Bill – might these ideas be incorporated into that legislation?

What Else Must Be Done

My work is guided by three premises:

1) Robust federal leadership is crucial:

- The Constitution gives primacy to federal agencies in managing imports and interstate trade.

- Only a consistent approach can protect trees (and other plants) from non-native pests that spread across state lines.

- Federal agencies have more resources than state agencies individually or in likely collective efforts – even after decades of budget and staffing cuts.

2) Success depends on a continuing, long-term effort founded on institutional and financial commitments commensurate with the scale of the threat. This requires stable funding; guidance by research and expert staff; and engagement by non-governmental players and stakeholders. Unfortunately, as I discuss below, funding has been neither adequate nor stable.

3) Programs’ effectiveness needs to be measured. Measurement must focus on outcomes, not just effort (see National Environmental Coalition on Invasive Species’ vision document).

Preventing New Introductions – Challenges and Solutions

We cannot prevent damaging new introductions without addressing two specific challenges.

1) Wood packaging continues to pose a threat despite past international and national efforts. As documented in my recent blogs, the numbers of shipping containers – presumably with wood packaging – are rising. Since 2010, CBP has detected nearly 33,000 shipments in violation of ISPM#15. The numbers of violations are down in the most recent years. However, a high proportion of pest-infested wood continues to bear the ISPM#15 mark. So, ISPM#15 is not as effective as it needs to be.

We at CISP hope that by mid-2022, a new analysis of the current proportion of wood packaging harboring pests will be available. Plus there are at least two collaborative efforts aimed at increasing industry efforts to find solutions – The Nature Conservancy with the National Wooden Pallet and Container Association; and the Cary Institute with an informal consortium of importers using wooden dunnage.

2) Imports of living plants (“plants for planting”) are less well studied so the situation is difficult to assess. However, we know this is a pathway that has often spread pests into and within the US. There have been significant declines in overall numbers of incoming shipments, but available information doesn’t tell us which types of plants – woody vs. herbaceous, plant vs. tissue culture, etc. – have decreased.

APHIS said, in a report to Congress (reference at end of blog), that introductions have been curbed – but neither that report nor other data shows me that is true.

Scientists are making efforts to improve risk assessments by reducing the number of organisms for which no information is available on their probable impacts (the “unknown unknowns”).

Solving Issues of Prevention

While I have repeatedly proposed radical revisions to the international phytosanitary agreements (WTO SPS & IPPC) that preclude prevention of unknown unknowns (see Fading Forests II and blog), I have also endorsed measures aimed at achieving incremental improvements in preventing introductions, curtailing spread, and promoting recovery of the affected host species.

The more radical suggestions focus on: 1) revising the US Plant Protection Act to give higher priority to preventing pests introductions than to facilitating free trade (FF II Chapter 3); 2) APHIS explicitly stating that its goal is to achieve a specific, high level of protection (FF II Chapter 3); 3) APHIS using its authority under the NAPPRA program to prohibit imports of all plants belonging to the 150 genera of “woody” plants that North America shares with Europe or Asia; 4) APHIS prohibiting use of packaging made from solid wood by countries and exporters that have a record of frequent violations of ISPM#15 in the 16 years since its implementation.

Another action leading to stronger programs would be for APHIS to facilitate outside analysis of its programs and policies to ensure the agency is applying the most effective strategies (Lovett et al. 2016). The pending Haack report is an encouraging example.

I have also suggested that APHIS broaden its risk assessments so that they cover wider categories of risk, such as all pests that might be associated with bare-root woody plants from a particular region. Such an approach could speed up analyses of the many pathways of introduction and prompt their regulation.

Also, APHIS could use certain existing programs more aggressively. I have in mind pre-clearance partnerships and Critical Control Point integrated pest management programs. APHIS should also clarify the extent to which these programs are being applied to the shipments most likely to transport pests that threaten our mainland forests, i.e. imports of woody plants belonging to genera from temperate climates. APHIS should promote more sentinel plant programs. Regarding wood packaging, APHIS could follow the lead of CBP by penalizing importers for each shipment containing noncompliant SWPM.

Getting APHIS to prioritize pest prevention over free trade in general, or in current trade agreements, is a heavy lift. At the very least, the agency should ensure that the U.S. prioritize invasive species prevention in negotiations with trading partners and in developing international trade-related agreements. I borrow here from the recent report on Canadian invasive species efforts. (I complained about APHIS’ failure to even raise invasive species issues during negotiation of a recent agricultural trade agreement with China.)

Solving Issues of Spreading Pests

The absence of an effective system to prevent a pest’s spread within the U.S. is the most glaring gap in the so-called federal “safeguarding system”. Yet this gap is rarely discussed by anyone – officials or stakeholders. APHIS quarantines are the best answer – although they are not always as efficacious as needed – witness the spread of EAB and persistence of nursery outbreaks of the SOD pathogen.

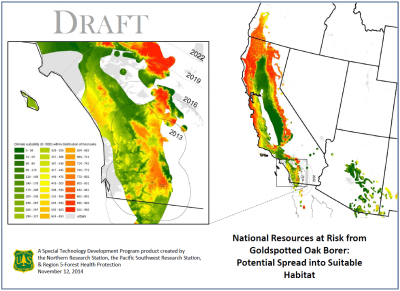

APHIS and the states continue to avoid establishing official programs targetting bioinvaders expected to be difficult to control or that don’t affect agricultural interests. Example include laurel wilt, and two boring beetles in southern California – goldspotted oak borer, Kuroshio shot hole borer and polyphagous shot hole borer and their associated fungi.

One step toward limiting pests’ spread would come from strengthening APHIS’ mandate in legislation, as suggested above. A second, complementary action would be for states to adopt quarantines and regulations more aggressively. For this to happen, APHIS would need to revise its policies on the “special needs exemption” [7 U.S.C. 7756]. Then states could adopt more stringent regulations to prevent introduction of APHIS-designated quarantine pests (Fading Forests III Chapt 3).

Finally, APHIS should not drop regulating difficult-to-control species – e.g., EAB. There are repercussions.

APHIS’ dropping EAB has not only reduced efforts to prevent the beetle’s spread to vulnerable parts of the West. It has also left states to come up with a coherent approach to regulating firewood; they are struggling to do so.

Considering interstate movement of pests via the nursery trade, the Systems Approach to Nursery Certification (SANC) program) is voluntary and was never intended to include all nurseries. Twenty-five nurseries were listed on the program’s website as of March 2020. It is not clear how many nurseries are participating now. The program ended its “pilot” phase and “went live” in January 2021. Furthermore, the program has been more than 20 years in development, so it cannot be considered a rapid response to a pressing problem.

Solving Issues of Recovery and Restoration via Resistance Breeding

I endorse the findings of two USFS scientists, Sniezko and Koch citations. They have documented the success of breeding programs when they are supported by expert staff and reliable funding, and have access to appropriate facilities. The principle example of such a facility is the Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Oregon. Regional consortia, e.g., Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Collaborative and Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation are trying to overcome gaps in the system. I applaud the growing engagement of stakeholders, academic experts, and consortia. Questions remain, though, about how to ensure that these programs’ approaches and results are integrated into government programs.

In Bonello et al., I and others call for initiating resistance breeding programs early in an invasion. Often other management approaches, e.g., targetting the damaging pest or manipulating the environment, will not succeed. Therefore the most promising point of intervention is often with by breeding new or better resistance in the host. This proposal differs slightly from my suggestion in the “30 years – solutions” blog, when I suggested that USFS convene a workshop to develop consensus on breeding program’s priorities and structure early after a pest’s introduction.

Funding Shortfalls

I have complained regularly in my publications (Fading Forests reports) and blogs about inadequate funding for APHIS Plant Protection program and USFS Forest Health Protection and Research programs. Clearly the USDA Plant Pest and Disease Management and Disaster Program has supported much useful work. However, its short-term grants cannot substitute for stable, long-term funding. In recent years, APHIS has held back $14 – $15 million each year from this program to respond to plant health emergencies. (See APHIS program reports for FYs 20 and 21.) This decision might be the best solution we are likely to get to resolve APHIS’ need for emergency funds. If we think it is, we might drop §2 of H.R. 1389.

Expanding Engagement of Stakeholders

Americans expect a broad set of actors to protect our forests. However, these groups have not pressed decision-makers to fix the widely acknowledged problems: inadequate resources – especially for long-term solutions — and weak and tardy phytosanitary measures. Employees of federal and state agencies understand these issues but are restricted from outright advocacy. Where are the professional and scientific associations, representatives of the wood products industry, forest landowners, environmental NGOs and their funders, plus urban tree advocates – who could each play an important role? The Entomological Society’s new “Challenge” is a welcome development and one that others could copy.

SOURCES

Bonello, P., Campbell, F.T., Cipollini, D., Conrad, A.O., Farinas, C., Gandhi, K.J.K., Hain, F.P., Parry, D., Showalter, D.N, Villari, C. and Wallin, K.F. (2020) Invasive Tree Pests Devastate Ecosystems—A Proposed New Response Framework. Front. For. Glob. Change 3:2. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2020.00002

Green, S., D.E.L. Cooke, M. Dunn, L. Barwell, B. Purse, D.S. Chapman, G. Valatin, A. Schlenzig, J. Barbrook, T. Pettitt, C. Price, A. Pérez-Sierra, D. Frederickson-Matika, L. Pritchard, P. Thorpe, P.J.A. Cock, E. Randall, B. Keillor and M. Marzano. 2021. PHYTO-THREATS: Addressing Threats to UK Forests and Woodlands from Phytophthora; Identifying Risks of Spread in Trade and Methods for Mitigation. Forests 2021, 12, 1617 https://doi.org/10.3390/f12121617ý

Krishnankutty, S., H. Nadel, A.M. Taylor, M.C. Wiemann, Y. Wu, S.W. Lingafelter, S.W. Myers, and A.M. Ray. 2020. Identification of Tree Genera Used in the Construction of Solid Wood-Packaging Materials That Arrived at U.S. Ports Infested With Live Wood-Boring Insects. Journal of Economic Entomology 2020, 1 – 12

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L. Parke, and K.O. Britton. 2012. Live plant imports: the major pathway for forest insect and pathogen invasions of the US. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012; 10(3):135-143

Lovett, G.M., M. Weiss, A.M. Liebhold, T.P. Holmes, B. Leung, K.F. Lambert, D.A. Orwig, F.T. Campbell, J. Rosenthal, D.G. McCullough, R. Wildova, M.P. Ayres, C.D. Canham, D.R. Foster, SL. Ladeau, and T. Weldy. 2016. NIS forest insects and pathogens in the US: Impacts and policy options. Ecological Applications, 26(5), 2016, pp. 1437–1455

Mech, A.M., K.A. Thomas, T.D. Marsico, D.A. Herms, C.R. Allen, M.P. Ayres, K.J. K. Gandhi, J. Gurevitch, N.P. Havill, R.A. Hufbauer, A.M. Liebhold, K.F. Raffa, A.N. Schulz, D.R. Uden, & P.C. Tobin. 2019. Evolutionary history predicts high-impact invasions by herbivorous insects. Ecol Evol. 2019 Nov; 9(21): 12216–12230.

Poland, T.M., Patel-Weynand, T., Finch, D., Miniat, C. F., and Lopez, V. (Eds) (2019), Invasive Spp in Forests and Grasslands of the US: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the US Forest Sector. Springer Verlag. (in press).

Roy, B.A., H.M Alexander, J. Davidson, F.T Campbell, J.J Burdon, R. Sniezko, and C. Brasier. 2014. Increasing forest loss worldwide from invasive pests requires new trade regulations. Front Ecol Environ 2014; 12(8): 457–465

Schulz, A.N., A.M. Mech, M.P. Ayres, K. J. K. Gandhi, N.P. Havill, D.A. Herms, A.M. Hoover, R.A. Hufbauer, A.M. Liebhold, T.D. Marsico, K.F. Raffa, P.C. Tobin, D.R. Uden, K.A. Thomas. 2021. Predicting non-native insect impact: focusing on the trees to see the forest. Biological Invasions.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Report on the Arrival in the US of Forest Pests Through Restrictions on the Importation of Certain Plants for Planting. https://www.caryinstitute.org/sites/default/files/public/downloads/usda_forest_pest_report_2021.pdf

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm