I last blogged about the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) two years ago. At that time, this insect from Asia (where else?) was established in some portions of six counties in southeastern Pennsylvania. While its principal host is tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), it was thought to feed on a wide range of plants, especially during the early stages of its development. Apparent hosts included many of the U.S.’s major canopy and undertory forest trees, e.g., maples, birches, hickories, dogwoods, beech, ash, walnuts, tulip tree, tupelo, sycamore, poplar, oaks, willows, sassafras, basswood, and elms. The principal focus of concern, however, is the economic damage the lanternflies cause to grapes, apples and stone fruits (e.g., peaches, plums, cherries), hops, and other crops.

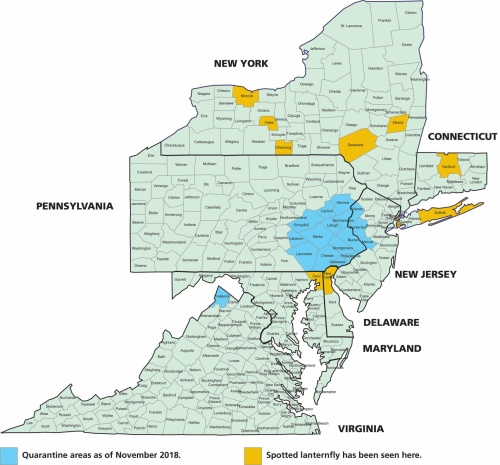

In the two years since my first blog, the spotted lanternfly has spread – both through apparent natural flight (assisted by wind) and through human transport of the egg masses and possibly adults. By autumn 2018, detections of one or a few adults – alive or dead – had been found in six additional states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia.

prepared by Cornell University

How many of these detections signal an outbreak? It is too early to know.

Impacts of the Government Shutdown

Unfortunately the federal government shutdown forced the cancellation of the annual USDA invasive species research meeting that occurs each January. The spotted lanternfly was to be the focus of six presentations. The most important of these was probably APHIS’ explanation of “where we are and where we are going.” The cancellation eliminated one of the most important opportunities for researchers to exchange information and ideas that could spur important insights. Equally important, the cancellation hampered communication of insights to practitioners trying to improve the pest’s management.

One pressing question was not on the meeting’s agenda, however. Would a much more aggressive and widespread response in 2014, when the lanternfly was first detected, have eradicated this initial outbreak? I have long thought that this question should be asked for every new pest program, so that we learn whether a too-cautious approach has doomed us to failure. However, authorities never address the issue – at least not in a public forum.

The shutdown also had an even more alarming impact. It interruptedaid by USDA APHIS and the Forest Service to states that should be actively trying to answer this question. Winter is the appropriate season to search for egg masses. It is also the season to plan for eradication projects.

For the first several years, funding of studies of the lanternfly’s lifecycles and host preferences, research on possible biological or chemical treatments, and outreach and education came in the form of competitive grants under the auspices of the Farm Bill Section 10007. This funding totaled $5.5 million to Pennsylvania.

This commitment pales compared to Asian longhorned beetle or emerald ash borer h— which were also poorly known when they were first detected in the United States.

At the same time, the Pennsylvania infestation spread. It is now known to be established in portions of 13 counties and outbreaks were detected in neighboring Delaware and Virginia. h

This spread – and resulting political pressure – persuaded APHIS to multiply its engagement. A year ago, USDA made available $17.5 million in emergency funds from the Commodity Credit Corporation (that is, the funds are not subject to annual Congressional appropriation). APHIS said it would use the additional funds to expand its efforts to manage the outer perimeter of the infestation while the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture would focus on the core infested area. APHIS said it would use existing (appropriated) resources to conduct surveys, and control measures if necessary, in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Virginia.

Summary of Latest Status in the Seven States

(see also the write-up here)

Pennsylvania: infestation established (quarantine declared) in portions of thirteen counties (Berks, Bucks, Carbon, Chester, Delaware, Lancaster, Lebanon, Lehigh, Monroe, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, Schuylkill). The quarantine regulates movement of any living stage of the insect brush, debris, bark, or yard waste; remodeling or construction waste; any tree parts including stumps and firewood; nursery stock; grape vines for decorative or propagative purposes; crated materials; and a range of outdoor household articles including lawn tractors, grills, grill and furniture covers, mobile homes, trucks, and tile or stone. See the regulation here: https://www.agriculture.pa.gov/Plants_Land_Water/PlantIndustry/Entomology/spotted_lanternfly/quarantine/Pages/default.aspx

Delaware: The state had been searching for the insect since the Pennsylvania outbreak was announced. After detection of a single adult female in New Castle County in November 2017, survey efforts and outreach to the public were intensified. Another dead adult spotted lanternfly was found in Dover, Delaware, in October 2018.

Virginia: infestation established (quarantine declared) in one county. Multiple live adults and egg cases of spotted lanternfly were confirmed in the town of Winchester, Virginia (Frederick County), in January 2018. As noted in my earlier blog, this region is important for apple and other orchard crops and near Virginia’s increasingly important wine region.

New Jersey: The New Jersey Department of Agriculture began surveying for lanternflies along the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border (the Delaware River) once the infestation was known. It found no lanternflies before 2018. In the summer, however, live nymphs were detected in two counties, Warren and Mercer. In response, the state quarantined both those counties and one located between them, Hunterdon. The state planned to continue surveillance in the immediate areas where the species has been found as well as along the Delaware River border in New Jersey.

New York: In 2017, a dead adult lanternfly was found in Delaware County.

State authorities expressed concern about possible transport of lanternflies from the Pennsylvania infested area.

In Autumn 2018, New York authorities confirmed several detections, including a single adult in Albany and a second single adult in Yates County. In response, the departments of Environmental Conservation and Agriculture and Marketing began extensive surveys throughout the area. Initially they found no additional lanternflies.

However, a live adult was later detected in Suffolk County (on Long Island).

Connecticut: a single dead adult was found lying on a driveway at a private residence in Farmington, CT, in October 2018. The homeowner was a state government employee educated about the insect. Relatives had recently visited from Pennsylvania (Victoria Smith, Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, pers. comm.). Searches found no other spotted lanternflies on the property. The state plans additional surveys in the area to confirm that no other spotted lanternflies are present.

Maryland: A single adult spotted lanternfly (male) was caught in a survey trap in the northeast corner of Cecil County near the border of Pennsylvania and Delaware (an area of known infestation) in October 2018. Because of the lateness of the season and sex of the insect, the Maryland Department of Agriculture does not believe that the lanternfly has established there.

All the affected states are encouraging citizens to report any suspicious finds.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.