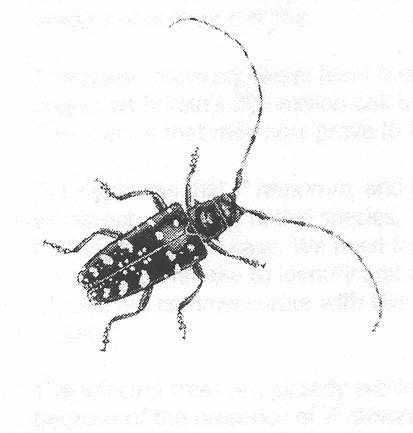

Here we go again … another Asian longhorned beetle population established in the U.S.

For the ninth time in 24 years, the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) has been found in North America – this time in South Carolina.

This means thousands – perhaps tens of thousands – of trees will be removed. Thousands more will be injected with imadacloprid. Millions of dollars will be spent. There will be uncounted aesthetic and spiritual losses. There will be unmeasured damage to at least the local environment – which probably includes bottomland hardwood forests – protection of which South Carolina has declared to be a conservation priority. All this destruction is necessitated by the need to prevent catastrophic damage to North America’s hardwood forests by the ALB.

By early August I have learned that the South Carolina outbreak has been present for seven years or longer, and that it might be related to the Ohio outbreak (which was detected in 2011 but was probably introduced at least four years earlier). APHIS reports that, as of the end of July, nearly 1,300 infested trees had been detected. The area around the neighborhood where the detection was made is swampy – complicating search and removal operations and probably home to many box elder and willows – preferred hosts for the ALB.

Why did we let this happen? Why do we persist with a policy that has allowed repeated introductions of this pest via the well-documented wood packaging pathway? After all, we learned about this risk 22 years ago – after the ALB introductions to New York and Chicago. We have had plenty of evidence that the policy is failing. We know how to stop this. Why do we – through our elected and appointed government officials – not act to prevent it?

What We Need: a New, Protective Policy

With live pests continuing to be present in wood packaging 14 years after the U.S. and Canada imposed the treatment requirements in ISPM#15 – and 21 years after we required China to treat its wood packaging – we urgently need better federal policy. I have long advocated:

- USDA APHIS join Bureau of Customs and Border Protection in penalizing violators for each violation; stop allowing five violations over a 12-month period before applying a penalty.

- APHIS and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) should apply their rights under Section 5.7 of the World Trade Organization Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement to immediately prohibit China from packaging its exports in wood. China can use crates and pallets made from such alternative materials as plastic, metal, or oriented strand board.

- APHIS and CFIA should being the process of supporting permanent application of this policy to China and other trade partners with poor compliance records. This step would require that they cite the need for setting a higher “level of protection” and then prepare a risk assessment to justify adopting more restrictive regulations.

- USDA Foreign Agriculture Service (FAS) should assist U.S. importers to determine which suppliers reliably provide wood packaging that complies with ISPM#15 requirements.

- USDA FAS and APHIS should help importers convey their complaints about specific shipments to the exporting countries’ National Plant Protection Organizations (NPPOs; departments of agriculture).

- APHIS should increase pressure on foreign NPPOs and the International Plant Protection Convention more generally to ascertain the reasons ISPM#15 is failing and to fix the problems.

- APHIS should fund more studies and audits of wood packaging to document the current efficacy of the standard, especially

- Update the Haack study of pest approach rate.

- Determine whether high rates of pest infestation of wood bearing the ISPM#15 mark results from fraud or failures of treatment – and whether any failures are due to mistakes/misapplication or shortcomings in the treatment themselves.

- Allocate the risk among the three major types of wood packaging: pallets, crates, and dunnage.

See also the recommendations of the Tree-Smart Trade program at www.tree-smart-trade.org

Tree-Smart also has a Twitter account: @treeSMARTtrade

Justification

The ALB poses a threat to 10% of US forests and nearly all of Canada’s hardwoods, so eradication of the South Carolina outbreak is essential. For a longer discussion of ALB introduction history, the threat, and eradication efforts to date, visit here. https://www.dontmovefirewood.org/pest_pathogen/asian-long-horned-beetle-html/).

Another ALB Outbreak in the US: No Surprise

This Chinese insect is a world traveler. It has been detected 36 times outside its natural range: in North America, Europe, and Japan. Seventeen of these outbreaks have been detected since 2012 (Eyre & Haack 2017). These 17 introduction have occurred six years or later after the 2006 implementation of the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) #15 – which was intended to reduce the likelihood of such introductions. .Ten of the outbreaks have been eradicated (Eyre & Haack 2017; APHIS press release October 2019). This includes four in the United States and Canada; see here.

Despite U.S. and international efforts, ALB and related pests have been detected continuously in imported goods. U.S. and European data (Eyre and Haack 2017) document rising numbers of Cerambycids detected in wood packaging in recent years. (For a description of pest prevention efforts, see Fading Forests II and III here and this blog).

It is also not surprising that the newly introduced pest is from China. It has long been among countries with the worst records on implementing ISPM#15.

The APHIS-CBP joint study of pest interceptions over the period 2012 – 2017 (Krishnankutty et al. 2020b) found the highest numbers of interceptions came from Mexico, China, and Turkey. During the period 2011 – 2016, China accounted for 11% of interceptions (APHIS interception database – pers. comm. January 2017).

These numbers reflect in part the huge volumes of goods imported from China. But China’s poor performance has continued, perhaps even increased in recent years. For example, consider the choice of wood used to manufacture packaging. Authorities recognized by the late 1990s that wood from plantations of Populus from northern China was highly likely to be infested by the Asian longhorned beetle. Yet, more than a dozen years later, this high-risk wood was still being used: between 2012 and 2017, the ALB was intercepted six times in wood packaging made of Populus wood – each time originating from a single wood-treatment facility in China (Krishnankutty et al. 2020b).

The location just outside Charleston also is not a surprise. Charleston ranked seventh in receipt of incoming shipping containers in 2018. Charleston received 1,022,000 containers, or TEUs measured as 20-foot equivalents, in 2018 (DOT report). This was a 14% increase over the 894,000 TEUs in 2017 http://www.marad.dot.gov/MARAD_statistics/index.html – click on “trade statistics”, then “US Waterborne trade” (1st bullet). I expect decreased import volumes in 2019 and 2020 due to the tariffs/trade war and the 2020 economic crash linked to the Covid-19 virus.

Why US and International Policy Still Fails

Leung et al. (2014) estimated that implementation of the International Standard of Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM)#15 resulted in only a 52% reduction in pest interceptions. They concluded that continued implementation at the 2009 level of efficacy could triple the number of wood borers established (not just intercepted) in the U.S. by 2050.

Since 2010 the Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has found an average of 794 shipments infested by pests each year (Harriger). In 2019 specifically, live pests were found in 747 shipments (Stephen Brady, CBP, April 2020). These violations were occurring four to 13 years after the U.S. began implementing ISPM#15 in 2006. According to my calculations, based on estimates of pest approach rates by Haack et al. (2014), these detections probably represented about eight percent of the total number of infested shipments entering the country each year.

And there are good reasons to think this estimate is low. First, Haack et al. (2014) did not include imports from China, Canada, or Mexico in their calculations. Both China and Mexico rank high among countries with poor compliance records. Second, Haack and Meissner based their calculations on 2009 data – 11 years out of date. Since 2009, ISPM#15 has been amended to make it more effective. The most important change was restricting the size of bark remnants that may remain on wood. Also, countries and trading companies have 11 more years of implementation – so they might have improved their performance. I have asked several times that APHIS commission a new analysis of Agriculture Quarantine Inspection Monitoring data. We all need an up-to-date determination of the pest approach rate, not only before but also after the CBP action. Without it, there’s no evidence whether the more aggressive enforcement stance CBP adopted in 2017 (see below) has led to reductions in non-compliant shipments at the border.

Another demonstration of the failure of ISPM#15 is the repeated presence of the velvet longhorned beetle (Trichoferus (=Hesperophanes) campestris) in wood packaging and its establishment in at least three states (Krishnankutty, et al. 2020a; also see the discussion in my recent blog here).

Astoundingly, data indicate that 97% of wood packaging infested with pests bears the stamp certifying that the wood has been treated according to the requirements of ISPM#15 – and hence should be pest-free (Eyre et al. 2018; CBP interception data). In other words, the presence of the stamp is not a reliable indicator of whether the wood has indeed been treated nor that it is pest-free. Scientists have speculated for years why this is the case. ALB’s new arrival provides an impetus to finally answer this question and to ensure policy reflects the answer.

What Federal Agencies Are Doing to Better Prevent Introductions

In contrast to such a comprehensive approach, this is what changes are under way.

CBP strengthened its enforcement in November 2017. The agency’s total “enforcement actions” increased by 400% from 2017 to 2018 (Sagle, pers. comm). The 2019 data show decreases, in absolute numbers, from earlier years in all categories: a 19% decrease below 2010-2018 in average number of shipments intercepted; a 13% decrease in number of shipments intercepted because the wood packaging lacked the ISPM#15 mark; and a decrease of 6% in the number of shipments intercepted that had a quarantine pest (Stephen Brady, CBP, April 2020). However, one year of interception data do not provide a basis for saying whether CBP’s stronger enforcement has resulted in a lower number of shipments in violation of ISPM#15 approaching our shores. Again, I call for APHIS to repeat Haack et al. (2014) study.

Harriger reported that CBP is also trying harder to educate importers, trade brokers, affiliated associations, CBP employees, and international partners about ISPM#15 requirements. CBP wants to encourage them to take actions to reduce all types of non-compliance: lack of documentation, pest presence in both wood packaging and shipping containers, etc.

APHIS has not altered its long-standing policy of allowing an importer to rack up five violations over a 12-month period before imposing a penalty. Instead, APHIS has focused on “educating” trade partners to encourage better compliance. For example, APHIS worked with Canada and Mexico – through the North American Plant Protection Organization — to sponsor workshops for agricultural agencies and exporters in Asia and the Americas

APHIS also planned to host international symposia on wood packaging issues as part of events recognizing 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health. These symposia have been postponed by travel and other restrictions arising from the coronavirus pandemic.

The Broader Significance of Continuing Wood Packaging Problems

The premise of the international phytosanitary system – the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (SPS Agreement) and the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) – is that importing countries should rely on exporting countries to take the actions necessary to meet the importing countries’ plant health goals. The ISPM#15 experience undermines the very premise of these international agreements.

If we cannot clean up the wood packaging pathway – which involves boards or logs that are, after all, already dead – it bodes poorly for limiting pests imported with other commodities that are pathways for tree-killing pests – especially living plants (plants for planting). Living plants are much more easily damaged or killed by phytosanitary measures, so ensuring pest-free status of a shipment is even more difficult. (A longer discussion of the SPS Agreement and IPPC is found in Chapter III of Fading Forests II, available here.

SOURCES

Eyre, D., R. Macarthur, R.A. Haack, Y. Lu, and H. Krehan. 2018. Variation in Inspection Efficacy by Member States of SWPM Entering EU. Journal of Economic Entomology, 111(2), 2018, 707–715)

Haack RA, Britton KO, Brockerhoff EG, Cavey JF, Garrett LJ, et al. (2014) Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the US. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611.

Kevin Harriger, US CBP. Presentations to the annual meetings of the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases over appropriate years. See, e.g., https://continentalforestdialogue.org/continental-dialogue-meeting-november-2018/

Krishnankutty, S.M., K. Bigsby, J. Hastings, Y. Takeuchi, Y. Wu, S.W. Lingafelter, H. Nadel, S.W. Myers, and A.M. Ray. 2020a. Predicting Establishment Potential of an Invasive Wood-Boring Beetle, Trichoferus campestris (Coleoptera:) in the United States. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, XX(X), 2020, 1–12

Krishnankutty, S., H. Nadel, A.M. Taylor, M.C. Wiemann, Y. Wu, S.W. Lingafelter, S.W. Myers, and A.M. Ray. 2020b. Identification of Tree Genera Used in the Construction of Solid Wood-Packaging Materials That Arrived at U.S. Ports Infested With Live Wood-Boring Insects. Commodity Treatment and Quarantine Entomology

Leung, B., M.R. Springborn, J.A. Turner, E.G. Brockerhoff. 2014. Pathway-level risk analysis: the net present value of an invasive species policy in the US. The Ecological Society of America. Frontiers of Ecology.org

Meissner, H., A. Lemay, C. Bertone, K. Schwartzburg, L. Ferguson, L. Newton. 2009. Evaluation of Pathways for Exotic Plant Pest Movement into and within the Greater Caribbean Region. Caribbean Invasive Species Working Group (CISWG) and USDA APHIS Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory

USDA APHIS interception database – pers. comm. January 2017.

USDA APHIS press release dated September 12, 2018

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Press Release No. 0133.20, January 27, 2020

U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration, U.S. Waterborne Foreign Container Trade by U.S. Customs Ports (2000 – 2017) Imports in Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units (TEUs) – Loaded Containers Only at https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/freight_analysis/nat_freight_stats/docs/06factsfigures/fig2_9.htm and

US Department of Transportation. Port Performance Freight Statistics in 2018 Annual Report to Congress 2019 https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/43525

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.