Carrying out a pest eradication program is a tough job – technically difficult, expensive, frustrating, and often generating opposition from various groups. But often eradication is crucial. It is the essential backup to the strategies aimed at preventing introduction in the first place.

USDA APHIS is responsible for developing and implementing eradication programs targeting non-native plant pests – including those that kill trees. APHIS just released an environmental impact statement covering its efforts to eradicate the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) it is available here. The EIS justifies both the eradication program targeting this species, itself, as well as the specific measures used.

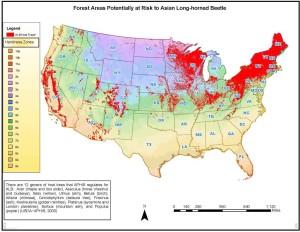

The ALB is one of the most damaging pests ever introduced to North America; it would kill trees in 12 genera which collectively grow in forests across the 48 continental states. In the Northeast (a 20-state area reaching from Minnesota south to Missouri and east to Maine and Virginia), trees vulnerable to ALB dominate two forest types that collectively make up 45% of all forests. Indeed, these vulnerable forests cover almost 20% of the entire land area of these states. For a longer description of the ALB threat, read about the pest in the Gallery of Pests and consider the map below.

USGS. 2014. Digital representations of tree species range maps from “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little Jr. (and other publications).

The APHIS program – carried out with the help of the USDA Forest Service, other federal agencies, state agencies, local governments, and citizen volunteers – has succeed in eradicating ALB from six sites.

The EIS also makes clear what a tremendous effort such an eradication program demands. APHIS began trying to eradicate ALB 19 years ago, upon discovery of the outbreak in Brooklyn. Since then, APHIS has spent $500 million tackling outbreaks in five states, cut down more than 124,000 trees, and treated tens of thousands of additional trees with the systemic insecticide imidacloprid. Yet more work remains because large outbreaks in Worcester, Massachusetts and Clermont County, Ohio are not yet contained. Eradicating these outbreaks will take many years.

The EIS does not explicitly acknowledge the strong opposition that APHIS has faced from people who were understandably anguished over loss of their trees – especially the trees that were still healthy but posed a risk of enabling ALB to persist and spread across the Continent. Some of the opponents were further angered because they believed – based on misunderstandings or false information – that removing those trees was not a necessary action to protect trees across the Continent.

APHIS deserves our gratitude for persisting in its eradication efforts, despite vocal opposition, uncertainty over funding levels, and the many discouraging setbacks encountered while the agency was trying to improve methods to detect ALB and to contain pest populations.

I’m discouraged that the people who owe the most to APHIS don’t recognize the agency’s efforts. Unfortunately, many appear either to take these actions for granted or to ignore them completely. APHIS received only 27 comments on its notice that it would develop the EIS, and only 14 comments on the EIS itself.

Who should have commented? Everyone who cares about:

• The health of hardwood forests composed of maples, elms, ash, poplars, buckeyes, birch, or willows; these genera are most dense in forests of the Northeast, but – as the map above shows – they grow in forested areas throughout the “lower 48”.

• The health of urban forests and the ecosystem and public health benefits they provide. Cities with high proportions of trees vulnerable to ALB range from Seattle to Boston.

• Clean drinking water for. In the Northeast, 48% of the water supply originates on forestlands – and 45% of those forest lands are composed primarily of species that are vulnerable to ALB.

• The economy and jobs in the Northeast. Vulnerable hardwoods produce timber and maple syrup and are the foundation of the “leaf peeper” tourism industry.

Those who actually did provide comments included:

• Six state departments of Agriculture and their national association, the National Plant Board;

• Four officials in other state agencies (primarily forestry or environmental quality);

• Four officials from other federal agencies (three from National Park Service, one from Fish and Wildlife Service);

• About 20 representing the public, of which:

o Four were affiliated with the maple syrup industry;

o Six organizations focused on wildland or rural forests.

I hope that the next time APHIS seeks public input on its programs, the following organizations will provide thoughtful input:

• the national or regional representatives of state forestry departments;

• the many environmental organizations that engage so actively on other types of forest management issues;

• the organizations that advocate for planting and protecting urban forests;

• the groups that support recreation in forests and on associated lakes and streams;

• the organizations that advocate for protection of wildlife habitat.

APHIS tried hard to inform all who might be interested. APHIS posted the scoping notice and availability of the draft environmental impact statement in the Federal Register. Also, it posted alerts on its Stakeholder Registry (which contains almost 12,000 contacts); its e-newsletter; its Facebook and Twitter accounts; and the agency’s “news and information” and ALB-related web pages. In addition, APHIS notified ALB project managers in New York, Massachusetts, and Ohio and their state counterparts and asked that they notify their key contacts; tribal contacts; USDA Forest Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service contacts; plus several specific partners and organizations. APHIS also issued a press release which it shared with federal and state partners.

Why does it matter that APHIS received so few comments? This silence gives political and agency leaders the impression that the American public does not support efforts to prevent the spread or to eradicate tree-killing insects and pathogens. I hope this is not true!

This negative impression remains even if there are many stakeholders who are pleased with the program’s direction and progress. Their choice not to voice their support meant that only those who object to at least some components of the program are heard in the policy arena.

I plead with you – get involved! Support those parts of APHIS’s eradication and containment programs that you think are wise. Criticize those components that you think should be strengthened or changed.

Posted by Faith Campbell