Here I update information on two of the major pathways by which tree-killing pests enter the United States: wood packaging and living plants (plant for planting).

Wood Packaging

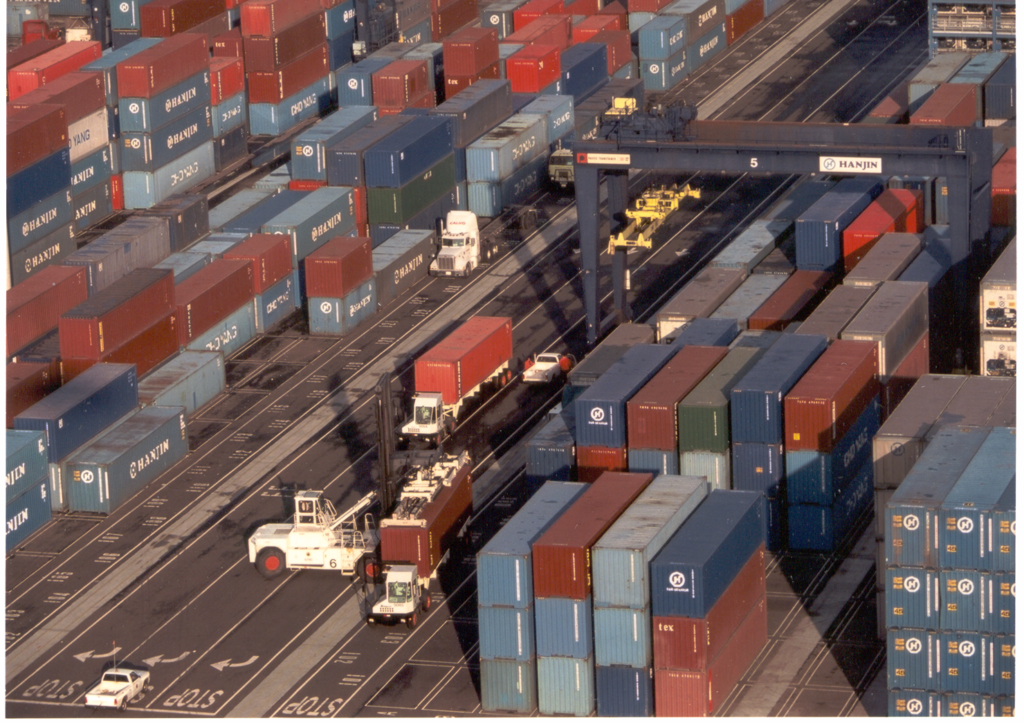

Looking at wood packaging material, we find rising volumes for both shipping containers – and their accompanying crates and pallets; and dunnage.

Crates and pallets – Angell (2021; full citation at the end of the blog) provides data on North American maritime imports in 2020. The total number of TEUs [a standardized measure for containerized shipment; defined as the equivalent of a 20-foot long container] entering North America was 30,778,446.U.S. ports received 79.6% of these incoming containers, or 24,510,990 TEUs. Four Canadian ports handled 11.4% of the total volume (3,517,464 TEUs; four Mexican ports 8.9% (2,749, 992 TEU). Angell provides data for each of the top 25 ports, including those in Canada and Mexico.

To evaluate the pest risk associated with the containerized cargo, I rely on a pair of two decade-old studies. Haack et al. (2014) determined that approximately 0.1% (one out of a thousand) shipments with wood packaging probably harbor a tree-killing pest. Meissner et al. (2009) found that about 75% of maritime shipments contain wood packaging. Applying these calculations, we estimate that 21,000 of the containers arriving at U.S. and Canadian ports in 2020 might have harbored tree-killing pests.

While the opportunity for pests to arrive is obviously greatest at the ports receiving the highest volumes of containers with wood packaging, the ranking (below) does not tell the full story. The type of import is significant. For example, while Houston ranks sixth for containerized imports, it ranks first for imports of break-bulk (non-containerized) cargo that is often braced by wooden dunnage (see below). Consequently, Houston poses a higher risk than its ranking by containerized shipment might indicate.

Also, Halifax Nova Scotia ranks 22nd for the number of incoming containerized shipments (258,185 containers arriving). However, three tree-killing pests are known to have been introduced there: beech bark disease (in the 1890s), brown spruce longhorned beetle (in the 1990s), and European leaf-mining weevil (before 2012) [Sweeney, Annapolis 2018]

The top ten ports receiving containerized cargo in 2020 were

Port 2020 market share 2020 TEU volume

Los Angeles 15.6% 4,652,549

Long Beach 13% 3,986,991

New York/New Jersey 12.8% 3,925,469

Savannah 7.5% 2,294,392

Vancouver BC 5.8% 1,797,582

Houston 4.2% 1,288,128

Manzanillo, MX 4.1% 1,275,409

Seattle/Tacoma 4.1% 1,266,839

Virginia ports 4.1% 1,246,609

Charleston 3.3% 1,024,059

Import volumes continue to increase since these imports were recorded. U.S. imports rose substantially in the first half of 2021, especially from Asia. Imports from that content reached 9,523,959 TEUs, up 24.5% from the 7,649,095 TEUs imported in the first half of 2019. The number of containers imported in June was the highest number ever (Mongelluzzo July 12, 2021).

Applying the calculations from Haack et al. (2014) and Meissner et al. (2009) to the 2021 import data, we find that approximately 7,100 containers from Asia probably harbored tree-killing pests in the first six months of the year. (The article unfortunately reports data only for Asia.) Industry representatives quoted by Mongelluzzo expect high import volumes to continue through the summer. This figure also does not consider shipments from other source regions.

Infested dunnage – Looking at dunnage, imports of break-bulk (non-containerized) cargo to Houston – the U.S. port which receives the most – are also on the upswing. Imports in April were up 21% above the pandemic-repressed 2020 levels.

Importers at the port complain that too often the wooden dunnage is infested by pests, despite having been stamped as in compliance with ISPM#15. CBP spokesman John Sagle confirms that CBP inspectors at Houston and other ports are finding higher numbers of infested shipments. CBP does not release those data, so we cannot provide exact numbers (Nodar, July 19, 2021).

The Houston importers’ suspicion has been confirmed by data previously provided by CBP to the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Insects and Diseases. From Fiscal Year 2010 through Fiscal Year 2015, on average 97% of the wood packaging (all types) found to be infested bore the stamp. CBP no longer provides data that touch on this issue.

Detection of pests in the dunnage leads to severe problems. Importers can face fines up to the full value of the associated cargo. Often, the cargo is re-exported, causing disruption of supply chains and additional financial losses (Nodar, July 19, 2021).

In 2019 importers and shippers from the Houston area formed an informal coalition with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies to try to find a solution to this problem. The chosen approach is for company employees to be trained in CBP’s inspection techniques, then apply those methods at the source of shipments to identify – and reject – suspect dunnage before the shipment is loaded. In addition, the coalition hopes that international inspection companies, which already inspect cargo for other reasons at the loading port will also be trained to inspect for pests. Steps to set up such a training program were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, but are expected to resume soon (Nodar, July 19, 2021).

Meanwhile, the persistence of pests in “treated” wood demands answers to the question of “why”. Is the cause fraud – deliberate misrepresentations that the wood has been treated when it has not? Or is the cause a failure of the treatments – either because they were applied incorrectly or they are inadequate per se?

ISPM#15 is not working adequately. I have said so. Gary Lovett of the Cary Institute has said so (Nodar July 19, 2021). Neither importers nor regulators can rely on the mark to separate pest-free wood packaging from packaging that is infested.

APHIS is the agency responsible for determining U.S. phytosanitary policies. APHIS has so far not accepted its responsibility for determining the cause of this continuing issue and acting to resolve it. Preferably, such detection efforts should be carried out in cooperation with other countries and such international entities as the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) and International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO). However, APHIS should undertake such studies alone, if necessary.

In the meantime, APHIS and CBP should assist importers who are trying to comply by facilitating access to information about which suppliers often supply wood packaging infested by pests. The marks on the wood packaging includes a code identifying the facility that carried out the treatment, so this information is readily available to U.S. authorities.

Plants for Planting

A second major pathway of pest introduction is imports of plants for planting. Data on this pathway are too poor to assess the risk – although a decade ago it was found that the percentage of incoming shipments of plants infested by a pest was 12% – more than ten times higher than the proportion for wood packaging (Liebhold et al. 2012).

According to APHIS’ annual report, in 2020 APHIS and its foreign collaborators inspected 1.05 billion plants in the 23 countries where APHIS has a pre-clearance program. In other words, these plants were inspected before they were shipped to the U.S. At U.S. borders, APHIS inspected and cleared another 1.8 billion “plant units” (cuttings, rooted plants, tissue culture, etc.) and nearly 723,000 kilograms of seeds. Obviously, the various plant types carry very different risks of pest introduction, so lumping them together obscures the pathway’s risk. The report does not indicate whether the total volume of plant imports rose or fell in 2020 compared to earlier years.

SOURCES

Angell, M. 2021. JOC Rankings: Largest North American ports gained marke share in 2020. June 18, 2021. https://www.joc.com/port-news/us-ports/joc-rankings-largest-north-american-ports-gained-market-share-2020_20210618.html?utm_campaign=CL_JOC%20Port%206%2F23%2F21%20%20_PC00000_e-production_E-103506_TF_0623_0900&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Eloqua

Haack R.A., Britton K.O., Brockerhoff, E.G., Cavey, J.F., Garrett, L.J., et al. (2014) Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the United States. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096611

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L. Parke, and K.O. Britton. 2012. Live Plant Imports: the Major Pathway for Forest Insect and Pathogen Invasions of the US. www.frontiersinecology.org

Meissner, H., A. Lemay, C. Bertone, K. Schwartzburg, L. Ferguson, L. Newton. 2009. Evaluation of Pathways for Exotic Plant Pest Movement into and within the Greater Caribbean Region. A slightly different version of this report is posted at 45th Annual Meeting of the Caribbean Food Crops Society https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/agscfcs09/256354.htm

Mogelluzzo, B. July 12, 2021. Strong US imports from Asia in June point to a larger summer surge.

Nodar, J. July 19, 2021. https:www.joc.com/breakbulk/project-cargo/breakbult-volume-recovery-triggers-cbp-invasive-pest-violations_20210719.htm

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm