In August, the Morton Arboretum announced completion of a series of reports on the conservation status of major tree genera native to the continental United States. It is available here. The series of reports provides individual studies on Carya, Fagus, Gymnocladus, Juglans, Pinus, Taxus, and selected Lauraceae (Lindera, Persea, Sassafras). (Links to the individual reports are provided at the principal link above.)

The project was funded by the USDA Forest Service and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, The Morton Arboretum and Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S.

Each report provides a summary of the ecology, distribution, and threats to species in the genus, plus levels of ex situ conservation efforts. The authors hope that the data in these reports will aid in setting conservation priorities and coordinating activities among stakeholders. The aim is to further conservation of U.S. keystone trees.

These reports are part of the overall “Global Tree Assessment: State of Earth’s Trees” compiled under the auspices of Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) and IUCN SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. I discuss the global assessment in a separate blog to which I will link. The global report evaluates species’ status according to both the International Union of Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List and NatureServe. The process used is explained in each both the international and U.S. reports. For the U.S. overall, the global assessment identifies 1,424 species of tree, of which 342 (24%) are considered threatened. Hawai`i specifically is home to 241 endangered tree species (Megan Barstow, BGCI Conservation Officer, pers. comm.). See my blogs about threats to Hawaiian trees.

Like the global assessment, these individual studies of nine genera–carried out by the Morton Arboretum–are a monumental accomplishment. They vary in size and format. The report on oaks was completed first and is the most comprehensive. It is 220 pages, incorporating individual reports on 28 species of concern. The report on pines is 40 pages. It contains summary information and tables on all 37 pine species native to the United States, but lacks write-ups on individual species. The report on Lauracae is 25 pages; it evaluates the threat to five species in three genera from laurel wilt disease. The report on walnuts is 23 pages. It includes brief descriptions of six individual species, including butternut. The report on hickories (Carya spp.) is 20 pages. It provides brief description of 11 species. The report on yews is 18 pages. It covers three species. The report on Fagus addresses the single species in the genus, American beech. It is 17 pages. The shortest report is on another single species, Kentucky coffeetree; it is 15 pages.

Coverage of Threats from Non-Native Insects and Diseases in the Morton Arboretum Reports

In keeping with my focus, I concentrated my review of these nine reports on their handling of threats from non-native insects and pathogens. Six of the reports make some reference to pests – although the discussion is not always adequate, in my view. There are puzzling failures to mention some pathogens.

Genera subject to minimal threats from pests (native or non-native) include the monotypic Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus), whichis considered by the IUCN to be Vulnerable due habitat fragmentation, rarity on the landscape, and population decline.

A second such genus is Carya spp., the hickories. The entire genus is assessed by the IUCN as of Least Concern. The Morton study ranked two species, C. floridana and C. myristiciformis, as of conservation concern.

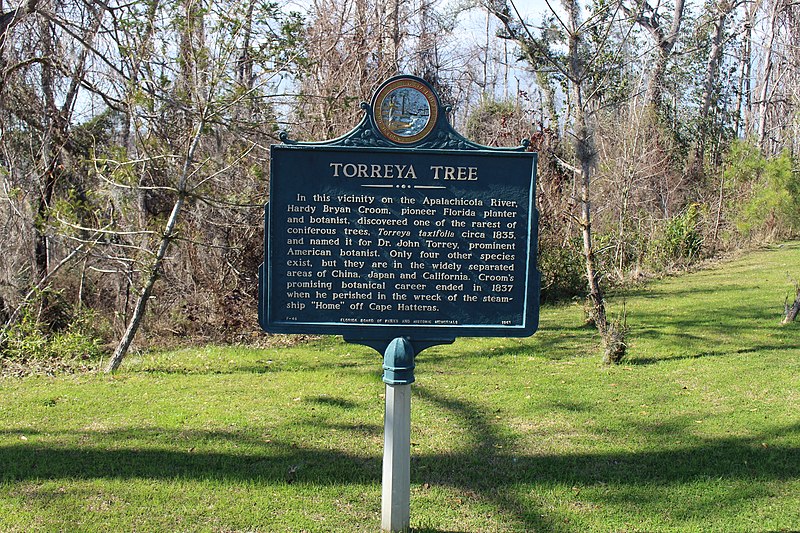

Three evaluators – the IUCN, the Morton Arboretum, and Potter et al. (2019) – agree that one of the three U.S. yew species, Florida torreya (Taxus floridana or Torreya taxifolia), is Critically Endangered because of its extremely small range, low population, and deer predation. Indeed, Potter et al. (2019) ranked Florida torreya as first priority of all forest trees in the continental United States for conservation efforts. However, the Morton Arboretum analysis makes no mention of the canker disease reported by, among others, the U.S. Forest Service.

A third of the 28 oak (Quercus spp.) species considered to be of conservation concern per the Morton study criteria are reported to be threatened by non-native pests. Pest threats to oak species not considered to be of conservation concerned were not evaluated in the report.

The Morton report records 37 pine species (Pinus spp.) as native to the U.S. Native and introduced insects and pathogens are a threat to many, especially in the West.

Two reports – those on the Lauraceae and beech – focus almost exclusively on threats from non-native pests. The report on walnuts (Juglans spp.) divides its attention between non-native pests and habitat conversion issues. This approach comes into some question as a result of the recent decision by state plant health officials to that thousand cankers disease does not threaten black walnut (J. nigra) in its native range.

Here I examine five of the individual genus reports in greater detail.

Oaks

The Morton report says that more than 200 oak species are known across North America, of which 91 are native in the United States. The study concludes that 28 of these native oaks are of conservation concern based on extinction risk, vulnerability to climate change, and low representation in ex situ collections. [The IUCN Red List recognizes 16 U.S. oak species as globally threatened with extinction.] Nearly all of the Morton’s report 28 species are confined to small ranges. In the U.S., regional conservation hotspots are in coastal southern California, including the Channel Islands; southwest Texas; and the southeastern states.

The summary opening section of the Morton report says 10 (36%) of the threatened oaks face a threat by a non-native pathogen. It admits that lack of information probably results in an underestimation of the pest risk. I found it difficult to confirm this overall figure by studying the detailed species reports because in some cases the threatening pathogen is not currently extant near the specific tree species’ habitat. I appreciate the evaluators’ concern about the potential for the pathogen, e.g., Phytophthora ramorum or oak wilt, to spread from its current range to vulnerable species growing on the other side of the continent. However, I wish the overview summary at the beginning of the report were clearer as to which species are currently being infected, which face a potential threat.

The report emphasizes the sudden oak death pathogen (SOD; Phytophthora ramorum), stating that it which currently poses a significant risk to wild populations of Q. parvula. However, the situation is more complex. As I note in my blog on threats to oaks, Q. parvula is divided into two subspecies. In the view of California officials, one, Q. p. var. shrevei, is currently threatened by SOD but the other, Q. p. var. parvula, (Santa Cruz Island oak) is currently outside the area infested by the pathogen. Perhaps the Morton Arboretum evaluators consider the potential risk to the second subspecies to be sufficient to justify stating that the pathogen poses a significant threat to the entire species; but I would appreciate greater clarity on this matter.

The report also mentions the potential threat to several rare oak species in the Southeast if SOD spreads there. While the Morton report rarely discusses species that have not been assessed as under threat, it does note that two species ranked as being of Least concern – coast live oak (Q. agrifolia) and California black oak (Q. kelloggii) – have been highly affected by SOD.

The Fusarium disease vectored by the polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers is mentioned as a threat to Engelmann (Q. engelmannii)and valley (Q. lobata) oaks. The latter, in particular, is considered by the Morton Arboretum assessors to be already much diminished by habitat conversion.

In the East, hydrological changes have facilitated serious damage to Ogelthorpe oak (Q. oglethorpensis) by the fungus that causes chestnut blight–Cryphonectria parasitica.

The Morton study mentions oak wilt (Ceratocystis or Bretziella fagacearum) as an actual or potential factor in decline of oaks in the red oak clade (Sect. Lobatae). Only one of the oak species discussed – Q. arkansana – is in the East, were oak wilt is established. The rest are red oaks in California, where oak wilt is not yet established. Again, there is no discussion of the impact of oak wilt on widespread species not now considered to be of conservation concern.

In the individual species profiles making up the bulk of the Morton report on oaks, but not in the summary, the Morton report also mentions the goldspotted oak borer (Agrilus auroguttatus) as an actual or potential factor in decline of the same oaks in the red oak group. The following species – Q. engelmanni, Q. agrifolia, Q. parvula, Q. pumila — are in California and at most immediate threat.

The Morton study also mentions several native insects that are attacking oaks, and oak decline. It calls for further research to determine their impacts on oak species of concern.

For analyses of the various pests’ impacts on oaks broadly, not focused on at-risk tree species, see my recent blog updating threats to oaks, posted here, and the pest profiles posted at www.dontmovefirewood.org

Pines

The Morton report lists 12 pine species as priorities out of the total of 37 species native to the United States. The report notes that the majority of the at-risk species in the West are threatened primarily by high mortality from one or more pests, in particular native bark beetles.

Six of the 12 priority species are five-needle pines affected by white pine blister rust (WPBR; Cronartium ribicola). The report contains maps showing the distribution of WPBR. In some cases, the native mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) contributes to immediate mortality. Presentation of recommendations is scattered and sometimes seems contradictory. Thus, P. longaeva (bristlecone pine) is said by the IUCN to be stable and is not listed among the 12 threatened species, but the Morton Arboretum assessors called for its receiving high conservation priority. P. albicaulis (whitebark pine) is a candidate for listing as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act, but the Morton Arboretum authors did not single it out for priority action beyond listing it among the dozen at-risk species.

The report also notes impacts by Phytopthora cinnamomi on pines; a maps shows the distribution of this non-native pathogen. A third non-native pathogen — pitch canker (Fusarium circinatum) — is mentioned as affecting Monterrey pine (P. radiata). Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana) is also affected by pitch canker, but this pathogen is ranked by the Morton study as causing only moderate mortality in association with other factors. Torrey pine is ranked as critically endangered and decreasing in populations.

The report also publishes the rankings developed by Potter et al. (2019). P. torreyana was the top-ranked pine, ranked at 18 (less urgent than, eastern hemlock).

The Morton study authors concluded that native U.S. pines are under serious threat. However, their economic, ecological, and cultural importance makes them obvious targets for continued conservation priority.

For my analysis of the various pests’ impacts on pines broadly, see the pest profiles posted at www.dontmovefirewood.org

Lauraecae

The Morton group analyzed five of the 13 species native to the United States, chosen based on three factors – tree-like habit, susceptibility to laurel wilt disease, and distribution in areas currently affected by the disease. They note the importance of Sassafras as a monotypic genus.

The Morton study notes the conservation status of several species needs changing due to the rapid spread of laurel wilt disease. I applaud this willingness to adjust, although I would be inclined to assign a higher ranking based on the most recent data from Olatinwo et al. (2021), cited here.

- Redbay (Persea borbonia) was assessed in 2018 as IUCN Least Concern; it is now being re-assessed, with a probable upgrade to Vulnerable. The Morton study says that recent evidence points towards the ecological extinction of P. borbonia from coastal forest ecosystems. Potter et al. (2019) ranked redbay as fifth most deserving of conservation effort overall.

- Silk bay (Persea humilis), endemic to Florida, is currently being assessed for the IUCN; it is recommended that it be designated as Near Threatened.

- Swamp bay (Persea palustris) is widespread. It is being assessed for the IUCN; it is recommended for the Vulnerable category.

- Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) is widely distributed. Sassafras had been assessed as of Least Concern as recently as the 2020 edition of the IUCN Red List. The Morton study notes that the current distribution of laurel wilt disease spans only a small percent of its range, so it does not pose an imminent threat to sassafras. However, cold-tolerance tests for the disease’s vector indicate the possibility of northward spread into more of the sassafras’ distribution. I note that laurel wilt is currently present in northern Kentucky and Tennessee.

American Beech

The Morton report notes that beech (Fagus grandifolia) is very widespread and a dominant tree in forests throughout the Northeastern United States and Canada. It is the only species in the genus native to North America, so presumably of high conservation interest. The report also notes its ecological importance (see also Lovett et al. 2006).

Beech bark disease is reported by the Morton Arboretum to have devastated Northeastern populations. The disease is well established in all beech-dominated forests in the United States, though it occurs on less than 30% of American beech’s full distribution. After mature beech die, thickets of young, shade-tolerant root sprouts and seedlings grow up, preventing regeneration of other tree species. Nevertheless, American beech was listed as of Least Concern by the IUCN in 2017.

The report makes no mention of beech leaf disease, which came to attention after the Morton assessment project had been almost completed. I think this is a serious gap that undermines the assessment not just of the species’ status in the wild but also of the efficacy of conservation efforts.

Walnuts

The Morton team evaluated five species of walnut (Juglans californica, J. hindsii, J. major, J. microcarpa, and J. nigra); and butternut (J. cinerea). Thousand cankers disease – caused by the fungus Geosmithia morbida, which is vectored by the walnut twig beetle (Pityophthorus juglandis) – is reported by the Morton team as second in importance to butternut canker. However, as I noted in a recent blog, the states that formerly considered the disease to pose a serious threat no longer think so and are terminating their quarantine regulations. This decision too recent for consideration by the Morton team.

One of the walnuts — Juglans californica (Southern Calif walnut) — is considered threatened by habitat loss. The rest of the walnuts are categorized by the IUCN as of Least Concern.

Butternut (Juglans cinerea), however, is considered by the IUCN to be Endangered. Although present across much of the Eastern deciduous forest, it is uncommon. It has suffered an estimated 80% population decline as a result of the disease caused by the butternut canker fungus Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum.

SOURCES

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Am beech. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum. August 2021

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Hickories. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Kentucky Coffeetree. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Denvir, A., Gill, D., Man, G., Pivorunas, D., Shaw, K., & Westwood, M. (2019). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Oaks. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Pines. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Laurels. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum. August 2021

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Walnuts. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum. August 2021

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Yews. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Lovett, G.M., C.D. Canham, M.A. Arthur, K.C., Weathers, and R.D. Fitzhugh. 2006. Forest Ecosystem Responses to Exotic Pests and Pathogens in Eastern North America. BioScience Vol. 56 No. 5 May 2006)

Olatinwo, R.O., S.W. Fraedrich & A.E. Mayfield III. 2021. Laurel Wilt: Current and Potential Impacts and Possibilities for Prevention and Management. Forests 2021, 12, 181.

Potter, K.M., M.E. Escanferla, R.M. Jetton, G. Man, B.S. Crane. 2019. Prioritizing the conservation needs of United States tree species: Evaluating vulnerability to forest insect and disease threats. Global Ecology and Conservation (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm