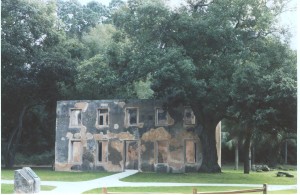

large redbay tree on Jekyll Island, Georgia; afterwards killed by laurel wilt

North America and other continents have been invaded by a growing number of tree-killing organisms – primarily pathogens – that attack a wide range of hosts100 species or more. Examples include sudden oak death / Phytopthora ramorum**, laurel wilt**, and the Fusarium fungus transported by the polyphagous and Kushiro borers**. These pathogens are more difficult to manage because of the range of potential hosts. Furthermore, a single introduced species can threaten numerous host species across large areas.

This is not a new phenomenon. Root rot caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi reached North America in the late 18th or early 19th Century, where it eliminated chestnut and chinkapin from low-elevation sites. P. cinnamomi is found in countries around the world. In Australia, it is killing a wide range of trees and shrubs across several plant families that constitute important components of Australia’s flora, including Myrtaceae, Proteaceae, Epacridaceae and Papilionaceae. There have been significant ecological impacts to plant communities and dependent wildlife in southeast and southwest Australia (Carnegie et al. 2016).

Nevertheless, the apparent proliferation of tree-killing organisms with multiple vulnerable hosts is troubling. So is the rapidity with which these organisms have been spread to distant places.

The disease called variously guava, eucalyptus, or myrtle rust – caused by Puccinia psidii** – attacks plants in “only” one family – the Myrtaceae. Its host list now includes more than 450 species in 73 genera. More than 200 of these are native species in Australia – where more than 10% of the plant species are members of this family. At least some of these plants are highly vulnerable to the rust; more than half of the individuals of the small tree Rhodomyrtus psidioides surveyed in a recent study were dead less than four years after the pathogen was introduced (Carnegie et al. 2016). New Zealand also has large numbers of Myrtaceae.

Guava rust is believed to be native to South and Central America. It was introduced to the Caribbean and southern Florida by the first decades of the 20th Century. Recently, the pathogen began to move. A new strain arrived in Florida in the 1990s. The rust was detected in Hawai`i in 2005. There, it is killing the native endangered shrub Eugenia koolauensis and an invasive shrub Syzygium jambos. In the past decade, guava rust has also invaded Japan, China, Australia, South Africa and New Caledonia (Carnegie et al. 2016).

Laurel wilt** also attacks “only” one plant family, the Lauraceae. While the United States is home to a relatively small number of plants in this family, Central America is a center of endemism for the family. In the United States, concern has focused on the disease’s threat to the avocado industry. However, the pathogen’s principal wild host, redbay, is likely to be virtually eliminated from U.S. forests except as seedlings too small to be attacked. (One ray of hope: Professor Jason Smith at the University of Florida is making progress on breeding redbays resistant to the disease.) Given the large number of presumably vulnerable trees and shrubs in Mexico and Central America, the spread of laurel wilt into Texas is worrisome.

Other pathogens attack shrubs and trees across several families. I noted Phyotphthora cinnamomi above. Other Phytophthoras share this ability.

Phytophthora ramorum** has a host list exceeding 130 herbaceous, shrub, and tree species in families ranging from maples to rhododendrons, oaks to hemlocks. P. ramorum is established in coastal parts of California and southern Oregon; and in western United Kingdom and Ireland. Another Phytophthora, P. kernoviae,** has a similarly broad host range. It is also established in the United Kingdom.

Fusarium dieback is caused by the fungus Fusarium euwallacea, which is transported by two beetles in the Euwallacea genus, called the polyphagous** and Kushiro shot hole borers. The beetle is known to attack more than 300 species of trees, shrubs, and vines in more than 58 plant families; hosts include species of oaks, maples, sycamores, hollies, and willows.

These multi-host pathogens are extremely difficult to contain – or even to detect early in the invasion. Australia tried to contain Puccinia rust, but conceded failure after only a few months. USDA APHIS does not have containment programs for any of three pathogens described here – despite the danger they pose to trees and other native vegetation.

Industry groups sometimes fund efforts to protect their crops. Avocado growers have spurred research on both laurel wilt and the Fusarium fungus — threats to their crop. However, academic researchers working on the impacts of laurel wilt on native ecosystems must scramble for funds. This is exactly the kind of research that requires – and deserves – increased public funding.

What should be done? Phytosanitary agencies need to improve greatly programs aimed at preventing introduction of pathogens to naïve hosts in new geographies. For the U.S., APHIS has already advocated two important improvements:

1) Prohibiting temporarily plants suspected of transporting known damaging pathogens. This action is allowed under the NAPPRA (not authorized for importation pending pest risk assessment) program.

2) Requiring foreign suppliers of living plant imports to implement “hazard analysis and critical control point” programs to ensure that the plants are pest-free during production and transport. This approach is allowed under ISPM#36 and would be authorized under pending changes to APHIS’ “Q-37” regulation. [See Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 80 April 25, 2013]

(See longer discussions of these programs in Fading Forests III, available here.)

Unfortunately, implementation of both of these programs has stalled. A list of plants proposed in May 2013 for NAPPRA restrictions has still not been finalized. Revisions to the Q-37 regulation proposed in April 2013 have also not been finalized.

USDA leadership should promptly implement these long-delayed improvements.

** indicates those pathogens and insect/pathogen complexes that are described briefly here

Source

Carnegie, A.J., A. Kathuria, G.S. Pegg, P. Entwistle, M. Nagel, F.R. Giblin. 2016. Impact of the invasive rust Puccinia psidii (myrtle rust) on native Myrtaceae in natural ecosystems in Australia. Biol Invasions (2016) 18:127–144 DOI 10.1007/s10530-015-0996-y

Posted by Faith Campbell