Plants sold in nurseries directly influence urban landscapes by providing gardens and other habitats that support humans and birds, insects, and other organisms. Doug Tallamy, though, has described ways that non-native plants fall short in providing habitat for native wildlife. Of course, non-native plants also indirectly influence natural landscapes by acting as a major source of invasive species. [see blog – includes links to regional invasive plant lists; and here] Imported plants also can carry non-native insects and pathogens – about which I blog frequently! To review these blogs, scroll down below the archives to the “categories” section and click on “plants as pest vectors”.

Now Kinlock, Adams, and van Kleunen (full citation at the end of this blog) have published a new paper that sheds more light on these issues. They analyzed the ornamental plants sold in US nurseries over 225 years (from 1719 to 1946). Their database, drawn from an earlier publication by Adams (see Sources at end of blog), included records of 5,098 ornamental vascular plant species offered for sale by 319 US nursery catalogs published over this period.

They note that present-day urban yards in the continental United States are planted in a diverse array of plants and the plants are predominately non-native species. Also, there is relatively little variation in species planted from one region to another, especially when compared to regional variation in natural areas). These patterns reflect the history of US horticulture.

Seventy percent (3,587) of the 5,098 ornamental vascular plant species offered by the 319 nurseries over those 200 years were non-native to the continental United States. They believe that the number of non-native species offered for sale has probably continued to increase in the 70 years since their study ended. They cite a study showing that 91% of tree species sold by nurseries in southern California during the 20th and early 21st centuries were not native to that state. A similar figure comes from a study of cultivated plants grown in Minneapolis–Saint Paul. There 66% of plants were non-native. (Kinlock, Adams, and van Kleunen note that 70% of species cultivated in yards of five British cities are non-native. In contrast, only 23% of cultivated plants in 18 Chinese cities were non-native.)

Kinlock, Adams, and van Kleunen note that two examples of non-native plants that have become invasive were among most common species available from nurseries beginning in the mid-19th Century: Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) was available in 78 nurseries, and Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergia) in 46 nurseries.

Historical Trends

The earliest commercial horticulture in colonies that became the United States was in the mid-17th Century. It involved imports of Eurasian fruit trees to establish orchards to provide familiar foods. Ornamental horticulture became popular earlier than I expected. Prince Nurseries was established in 1732 in Flushing, NY. It was followed by additional nurseries in New York, Philadelphia, and Massachusetts. Originally these businesses imported Old World nursery stock and seeds – again to provide familiar foods and take advantage of relationships with European contacts.

Nurseries proliferated in the 1820s in the population centers of the Atlantic coast. As people of European ancestry moved west, so did nurseries. Kinlock, Adams, and van Kleunen point out an interesting aspect of these changes: proliferation of both was aided by technology: steamboats, canals, highways, and improved mail service. Before 1800, nearly all nurseries were in the Mid-Atlantic, New England, and South. Nurseries appeared in the Great Lakes region by the 1830s. Expansion of rail lines connected nurseries from coast to coast by the 1870s. By 1890, there were more than 4,500 nurseries across the continent.

California, Florida, and Oregon are now the states with the most horticultural operations and sales (as of 2019).

The types of plants offered for sale proliferated throughout the 19th Century. The species richness of US nursery flora peaked in the early 20th Century. It decreased in the 1925 – 1946 period, possibly attributable to some combination of war-related interruptions to trade and a shift in gardeners’ focus away from ornamentals to vegetables. Another factor was adoption of international and interstate phytosanitary regulations in the early 20th Century. The post-World War II economic boom led to a new diversification of US nursery flora. In one study, a Los Angeles nursery experienced the largest increase in species richness during 1990–2011. They believe this increase was probably matched across the country. Global plant collection and importation mediated by US botanical gardens and nurseries remain active.

Over time, nursery floras in the various regions became more similar to each other. The floras of Mid-Atlantic and New England nurseries differed before 1775, then became similar. Nurseries in the Great Lakes region also shifted toward offerings in neighboring regions. Later, nurseries in the South and West also began offering a higher proportion of species commonly sold across the continent. The nursery floras of Great Lakes and Great Plains regions were consistently similar. Still, the flora in Western nurseries still retain some unique aspects. California is the only state with a Mediterranean climate. Nurseries there sought adapted plant species, especially from an entirely new source — Australasia. (The authors note that Acacia and Eucalyptus genera, while important in California horticulture, are invaders in Mediterranean zones worldwide.) One might expect the need for plants in the Southwest to be drought-tolerant would prompt a unique nursery flora. However, the ubiquity of irrigation since the late 19th Century has blunted this necessity. Still, nursery flora in the desert biome had the most phylogenetic uniformity. The article does not discuss pressure to choose xeriscapes or otherwise adjust to current water shortages.

Growing Importance of Non-Native Species – Especially from Asia

Kinlock, Adams, and van Kleunen define “native” species as those native to the state in which it is sold; “adventive” species as native to the continental United States but not the specific state; and non-native or alien species as not native to the continental United States.

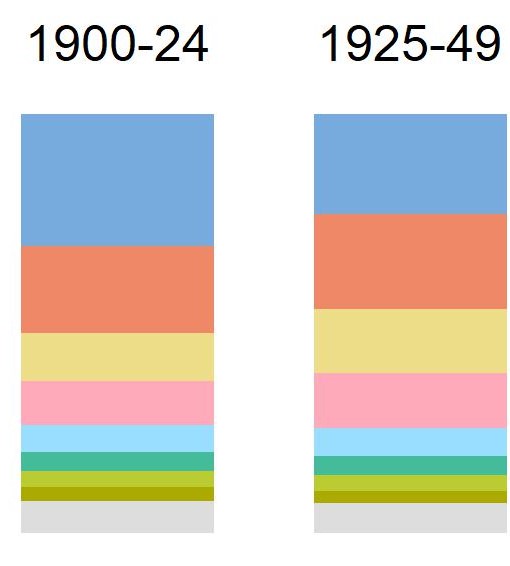

Applying these definitions, the proportion of native species in nursery flora has been consistently around 30-40% — except during the American Revolution. It rose to 70% in catalogs or advertisements published from 1775 to 1799. The authors do not speculate whether this reflected jingoism or interruptions in trade. The proportion of plant species that were adventive was 4% in the earliest period, then rose to 13% with improved transportation.

A large proportion of the native species offered in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were grown for export to Europe (think John Bartram).

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, plants from new regions of the world with unique genetic lineages became increasingly available. Until the mid-19th Century, most non-native plants came from Europe and Eurasia. Beginning in 1850, plants native to temperate Asia composed an increasing percentage of non-native nursery flora. In the period 1900 – 1924, 19% of the ornamental nursery flora originated from temperate Asia. By the next period, 1925 – 1946, this percentage rose to 20.8%.At the same time, North American species (including some from Mexico, Canada, or Alaska) composed 21.9% of the nursery flora. (see graph).

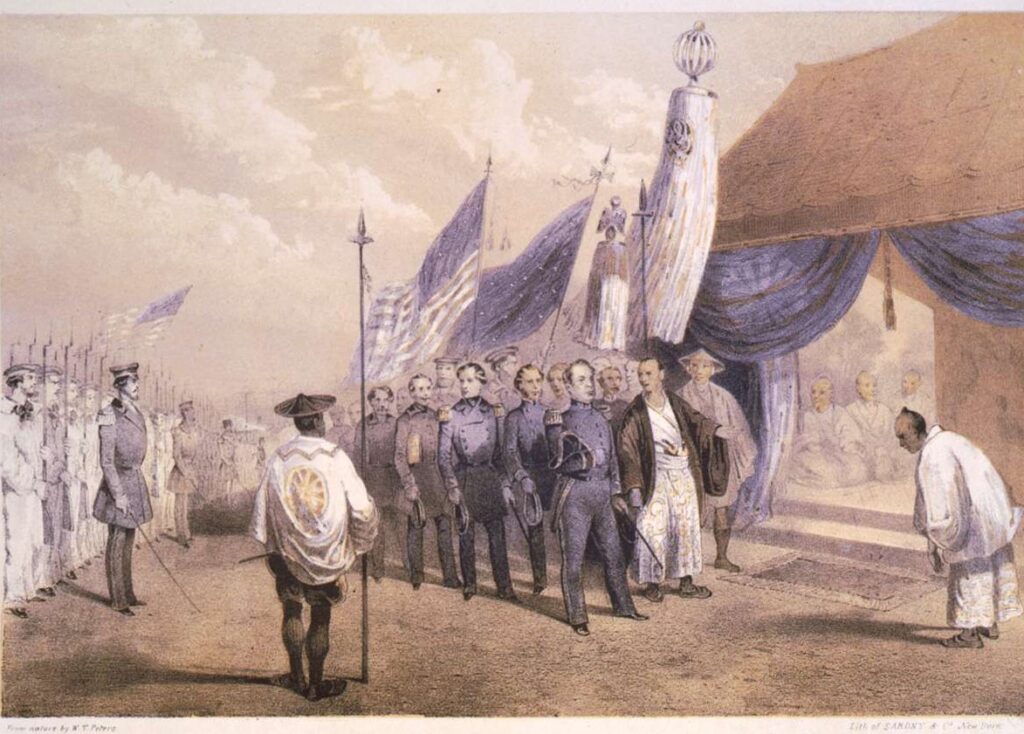

Plants from East Asia were particularly desirable for both biological and social reasons. First, because of climatic similarities between the two regions, East Asian plants thrived in the eastern United States. Second, popular ornamental genera had higher species richness in East Asia. Important social or cultural factors were a growing fascination with Japanese and Chinese-style gardens: forced “opening” of access to those countries in the 1840s and 1850s; and plant collecting expeditions sponsored by British and American institutions and private collectors. In 1898, the US Department of Agriculture established the Section of Seed & Plant Introduction; its purpose was to collect and cultivate economically useful non-native plants from throughout South America and Asia.

As I noted above, diversity of species in nursery offerings reached a peak in the first years of the 20th Century, concurrent with the first wave of US-sponsored plant collections; indeed, 70 species that were first listed after 1911 in their dataset were introduced by the USDA introduction program between 1912 -1942.

Counter-pressures and Counter-measures

There were counter pressures during this period that – as mentioned above—probably contributed to a decline in plant introductions in later years. In the 1890s, several US states began requiring inspection of imported plant materials (spurred by plant disease outbreaks caused by spread of San Jose scale from California).

Congress adopted the Plant Quarantine Act in 1912; USDA implemented it through stringent regulations issued in 1919 (Quarantine-37). I have already noted interruption of trade associated with WWI and WWII. Kinlock et al. don’t mention the Great Depression that intervened, but I think it played a role, too. On the other hand, Q-37 was relaxed to target particular species or regions based on pest risk analysis. The article says the relaxation began in the 1930s, but I believe it actually was during the 1970s; see Liebhold et al. 2012. I have blogged several times about how well the current regulations – including the “NAPPRA” program – prevent introductions of invasive plants or damaging plant pests. To review these blogs, scroll down below the archives to the “categories” section and click on “plants as pest vectors”.

SOURCES

Adams, D.W. 2004. Restoring American Gardens: An encyclopedia of heirloom ornamental plants. Timber Press

Kinlock, N.L., D.W. Adams, M. van Kleunen. 2022. An ecological and evolutionary perspective of the historical US nursery flora. Plants People Planet. 2022;1–14. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/ppp3

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L. Parke, and K.O. Britton. 2012. Live Plant Imports: the Major Pathway for Forest Insect and Pathogen Invasions of the US. www.frontiersinecology.org

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or