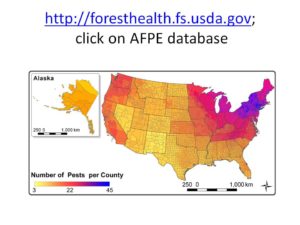

Numbers of non-native pests in counties of the 49 continental states; Map prepared by Andrew Liebhold, USFS in 2014. More recent introductions are not represented; nor are insects native to some part of North America

Numbers of non-native pests in counties of the 49 continental states; Map prepared by Andrew Liebhold, USFS in 2014. More recent introductions are not represented; nor are insects native to some part of North America

Currently, the Northeast and Midwest have the highest number of non-native, tree-killing insect and pathogen species (see map above). However, Pacific coast states have two-thirds the numbers of pest species of the Northeast – and are catching up. Two articles modeling the likelihood of new pest introductions point to the particular vulnerability of the Pacific Coast states – especially California – to pest introductions from Asia.

Koch et al. 2011 (see reference at the end of the blog) utilized various sources of information about volumes of imports likely to be associated with wood-boring pests — stone; raw wood and wood products (including crates & pallets); metals; non-metallic minerals; auto parts; etc. From this, the authors estimated both a nationwide establishment rate of wood-boring forest insect species and the likelihood that such insects might establish at more than 3,000 urban areas in the contiguous U.S. While their estimate was based on 2010 imports, they also projected rates for 2020.

See my blog from March 10 for various scientists’ estimates of the overall, nationwide rate of introduction. Koch et al. estimated the nation-wide introduction rate at between 0.6 and 1.89 forest insects and pathogen species per year for the period 2001–2010 and 0.36 and 1.7 species per year for 2011–2020. In other words, we should expect a new alien forest insect species to become established somewhere in the United States every 2–3 years. If one-tenth of these new introductions turn out to cause significant damage, then we can expect a “significant” new forest pest every 5–6 years.

Pacific coast states – especially California – are at highest risk.

Koch et al. evaluated the introduction risk for 3,126 urban areas across the country. The metropolitan area with the highest risk is Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana, California. For both 2010 and 2020, the predicted rates for a new pest establishing there is every 4–5 years.

Looking ahead to 2020, the situation worsens for three California metro areas – Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana; San Diego; and Riverside-San Bernardino. At San Francisco-Oakland, the predicted establishment rates remain steady. Most of the rest of the top 25 urban areas show decreases in establishment rate between 2010 and 2020.

This rising risk to California urban areas is driven by the growth of imports from Asia. For the four California urban areas, the establishment rate of Asian species is projected to increase 6–8% between 2010 and 2020. The Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana area could potentially expect the establishment of an alien forest insect species originating specifically from Asia alone (not the entire world) every 4–5 years.

[The polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers are examples of recently introduced pests from Asia. Both are described, inter alia, here; a distribution map for PSHB is available here.]

Koch et al. note that the Los Angeles metropolitan area has a dense human population with corresponding high demand for goods and materials, so a substantial proportion of imports clearing the port remains in the areas. Furthermore, widespread planting of non-native plants provides a range of potential hosts that can support invaders that would not otherwise become successfully established.

A second source also indicates a heightened risk to Pacific Coast states. Yemshanof et al. used similar modeling techniques to evaluate the risk of tree pest introductions to Canada … and to the U.S. in the form of transshipped goods. (See my earlier blog.)

The Yemshanof et al. model showed that 8% of all forest pests introduced to the U.S. on imported wood or wood packaging — as estimated by Koch et al. — would come through goods transshipped through Canada. The risk is highest to the Pacific Coast states since they are the most likely to receive Asian goods transiting through Canada.

Note that the phytosanitary agencies in both the U.S. and Canada proposed in 2010 that wood packaging originating in one of the countries and shipped to the other be required to meet the international regulations under ISPM#15. However, APHIS was unable to adopt this regulation under the Obama Administration, and such an action seems even less likely under the Trump Administration. Canada is unlikely to adopt the new rules without a coordinated U.S. action.

Southern California also imports lots of plants – another pathway for pest introductions.

Koch et al. suggest that authorities use these models to prioritize border control efforts (e.g., commodity inspections), post-border surveillance, and rapid-response measures. I see some problems with these suggestions. First, enhanced commodity inspections are not likely to measurably diminish the risk of introduction to the region. Second, rapid-response measures require both increased funds – which are expected to decrease; and political will. I have blogged several times about California’s decisions to not implement official, regulatory responses to recently detected pests.

Instead, people in the region should actively build alliances and press their regional political leaders – governors, mayors, senators, members of Congress – to demand that the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Congress adopt policies that will strengthen protection for the region’s trees.

New pest detected in California!

California authorities have detected a new woodboring beetle – the olive wood borer (Phloeotribus scarabaeoides). It was detected in an olive tree in a grape vineyard in Riverside County. This is the first detection of the species in the Western Hemisphere. Known or suspected hosts include several trees in the olive family (Oleaceae), including olive trees, privet, ash, and common lilac; as well as oleander (Apocynaceae).

Since this new pest is native to the Mediterranean region, it does not appear to be an example of the risk to California from Asia … The source (Diagnostic Network News; see below) does not speculate on the pathway by which the introduction occurred.

What Can We Do?

Ask your state’s Governor to

- Communicate to the USDA Secretary the need to amend policies & regulations

(Coordinate this effort with governors of other states.)

- Put forest pest issue on the agenda of National Governors’ Association

- Ask your state’s Congressional delegation to pressure USDA Secretary to amend policies and regulations

- Communicate concern about these pests to the media — and propose solutions.

Ask your state’s agricultural and forestry agency heads to

- Ask their national associations to support proposals to USDA Secretary & Congress. These associations include

- National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA)

- National Association of State Foresters (NASF) or its Western regional group, the Council of Western State Foresters

- Communicate to the media both the agency’s concern about tree pest threats and proposed solutions.

We can also act directly.

- Ask mayors and officials of affected towns and counties to

- Push proposals at regional or National Conference of Mayors or National Association of Counties

- Instruct local forestry staff to seek support of local citizen tree care associations, regional and national associations of arborists, Arbor Day & “Tree City” organizations, Sustainable Urban Forest Coalition, etc.

- Reach out to local media with a message that includes descriptions of policy actions intended to protect trees — not just damage caused by the pests

- Ask stakeholder organizations of which you are a member to speak up on the issue and support proposed solutions; e.g.,

- Professional/scientific associations

- Wood products industry

- Forest landowners

- Environmental NGOs

- Urban tree advocacy & support organizations

- Encourage like-minded colleagues in other states to press the agenda with their state & federal political players, agencies, & media.

- Communicate to the media both your concern about tree pest threats and proposed solutions.

What Specific Actions Should We Suggest be Taken?

I suggest a coordinated package. However, you might feel more comfortable selecting a few to address each time you communicate with a policymaker. Choose those on which you have the most expertise; or that you think will have the greatest impact.

- Make specific proposals, not vague ideas (see below for suggestions)

- Always include information about how the pests arrive/spread (pathways such as imports of crates & pallets, or woody plants for ornamental horticulture) and what we can do to clean up those pathways (Don’t just describe the “freak of the week”)

- Always point out that the burden of pest-related losses and costs falls on ordinary people and their communities. (Aukema et al. 2011 provides backup for this at the national level; try to get information about your state or city.)

- We need to restore a sense of crisis to prompt action – but not leave people feeling helpless! We need also to bolster understanding that we have been and can again be successful in combatting tree pests.

Specific actions that will reduce risk that pests pose to our trees:

- Importers switch from packaging made from solid wood (e.g., boards and 4”x4”s) to packaging made from other materials, e.g., particle boards, plastic, metal …

- Persuade APHIS to initiate a rulemaking to require importers to make the shift. This can be done – although international trade agreements require preparation of a risk assessment that justifies the action because it addresses an identified risk (see my earlier blogs about wood packaging).

- Create voluntary certification programs and persuade major importers to join them. One option is to incorporate non-wood packaging into the Department of Homeland Security Bureau of Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) existing Customs-Trade Partnership Against terrorism (C-TPAT) program.

- Tighten enforcement by penalizing shipments in packaging that does not comply with the current regulations

- Persuade CBP and/or USDA to end current policy under which no financial penalty is imposed until a specific importer has been caught five times in a single year with non-compliant wood packaging. APHIS has plenty of authority to penalize violators under the Plant Protection Act [U.S.C. §7734 (b) (1)].

- Restrict imports of woody plants that are more likely to transport pests that threaten our trees

- In 2011, APHIS adopted regulations giving it the power to temporarily prohibit importation of designated high-risk plants until the agency has carried out a risk assessment and implemented stronger phytosanitary measures to address those risks. Plants deserving such additional scrutiny can be declared “not authorized for importation pending pest risk assessment,” or “NAPPRA”. A list of plants posing a heightened risk was proposed nearly 4 years ago, but it has not been finalized – so imports continue. APHIS should revive the NAPPRA process and utilize prompt listing of plants under this authority to minimize the risk that new pests will be introduced.

- APHIS should finalize amendments to the “Q-37” regulation (proposed nearly 4 years ago) that would establish APHIS’ authority to require foreign suppliers to implement integrated programs to minimize pest risk. Once this regulation is finalized, APHIS could begin negotiating agreements with individual countries to adopt systems intended to ensure pest-free status of those plant types, species, and origins currently considered to pose a medium to high risk.

- Strengthen early detection/rapid response programs by

- Providing adequate funds to federal & state detection and rapid response programs. The funds must be available for the length of the eradication program – often a decade or more.

- Better coordinate APHIS, USFS, state, & tribal surveillance programs.

- Engage tree professionals & citizen scientists more effectively in surveillance programs.

SOURCES

Koch, F.H., D. Yemshanov, M. Colunga-Garcia, R.D. Magarey, W.D. Smith. Potential establishment of alien-invasive forest insect species in the United States: where and how many? Biol Invasions (2011) 13:969–985

Western Plant Diagnostic Network First Detector News. Winter 2017. Volume 10, Number 1.

Yemshanov, D., F.H. Koch, M. Ducey, K. Koehler. 2012. Trade-associated pathways of alien forest insect entries in Canada. Biol Invasions (2012) 14:797–812

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Posted by Faith Campbell