In August the USDA Forest Service published the agency’s 2020 assessment of the future of America’s forests under the auspices of the Resources Planning Act. [See United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Future of America’s Forests and Rangelands, full citation at the end of the blog.] To my amazement, this report is the first in the series (which are published every ten years) to address disturbance agents, specifically invasive species. In 2023! Worse, I think its coverage of the threat does not reflect the true state of affairs – as documented by Forest Service scientists among others.

This is most unfortunate because policy-makers presumably rely on this report when considering which threats to focus on.

Here I discuss some of the USFS RPA report and what other authors say about the same topics.

The RPA Report’s Principle Foci: Extent of the Forest and Carbon Sequestration

The USFS RPA report informs us that America’s forested area will probably decrease 1- 2% over the next 50 years (from 635.3 million acres to between 619 and 627 million acres), due largely to conversion to other uses. This decline in extent, plus trees’ aging and increases in disturbance will result in a slow-down in carbon sequestration by forests. In fact, if demand for wood products is high, or land conversion to other uses proceeds apace, U.S. forest ecosystems are projected to become a net source of atmospheric CO2 by 2070.

Eastern forests sequester the majority of U.S. forest carbon stocks. These forests are expected to continue aging – thereby increasing their carbon storage. Yet we know that these forests have suffered the greatest impact from non-native pests.

I don’t understand why the USFS RPA report does not explicitly address the implications of non-native pests. In 2019, Songlin Fei and three USFS research scientists did address this topic. Fei et al. estimated that tree mortality due to the 15 most damaging introduced pest species have resulted in releases of an additional 5.53 terragrams of carbon per year. Fei and colleagues conceded this is probably an underestimate. They say that annual levels of biomass loss are virtually certain to increase because current pests are still spreading to new host ranges (as demonstrated by detection of the emerald ash borer in Oregon). Also, infestations in already-invaded ranges will intensify, and additional pests will be introduced (for example, beech leaf disease).

I see this importance of eastern forests in sequestering carbon as one more reason to expand efforts to protect them from new pest introductions, and the spread of those already in the country, etc.

A second issue is the role of non-native tree species in supporting the structure and ecological functions of forests. Ariel Lugo and colleagues report that 18.8 million acres (7.6 million ha, or 2.8% of the forest area in the continental U.S.) is occupied by non-native tree species. (I know of no overall estimate for all invasive plants.) They found that non-native tree species constitute 12–23% (!) of the basal area of those forest stands in which they occur.

Lugo and colleagues confine their analysis of ecosystem impacts to carbon sequestration. They found that the contribution of non-native trees to carbon storage is not significant at the national level. In the forests of the continental states (lower 48 states), these trees provide 10% of the total carbon storage in the forest plots where they occur. (While Lugo and colleagues state that the proportion of live tree biomass made up of non-native tree species varies greatly among ecological subregions, they do not provide examples of areas on the continent where their biomass – and contribution to carbon storage — is greater than this average.) In contrast, on Hawai`i, non-native tree species provide an estimated 29% of live tree carbon storage. On Puerto Rico, they provide an even higher proportion: 36%.

In the future, non-native trees will play an even bigger role. Since tree invasions on the continent are expanding at ~500,000 acres (202,343 ha) per year, it is not surprising that non-native species’ saplings provide 19% of the total carbon storage for that size of trees in the lower 48 states (Lugo et al.).

Forming a More Complete Picture: Biodiversity, Disturbance, and Combining Data.

The USFS RPA report has a chapter on biodiversity. However, the chapter does not discuss historic or future diversity of tree species within biomes, nor the genetic diversity within tree species.

Treatment of Invasive Species

The USFS 2020 RPA report is the first to include a chapter on disturbance, including invasive species. I applaud its inclusion while wondering why they have included it only now? Why is the coverage so minimal? I think these lapses undercut the report’s purpose. The RPA is supposed to inform decision-makers and stakeholders about the status, trends, and projected future of renewable natural resources and related economic sectors for which USFS has management responsibilities. These include: forests, forest products, rangelands, water, biological diversity, and outdoor recreation. The report also has not met its claim to “capitalize on” areas where the USFS has research capacity. One excuse might be that several important publications have appeared after the cut-off date for the assessment (2020). Still, the report’s authors cite some of the evaluations that were in preparation as of 2020, e.g., Poland et al.

I suggest also that it would be helpful to integrate data from other agencies, especially the invasive species database compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, into the RPA. For example, the USGS lists just over 4,000 non-native plant species in the continental U.S. (defined as the lower 48 plus Alaska). On Hawai`i, the USGS lists 530 non-native plant species as widespread. Caveat: many of the species included in these lists probably coexist with the native plants and make up minor components of the plant community.

Specifically: Invading Plants

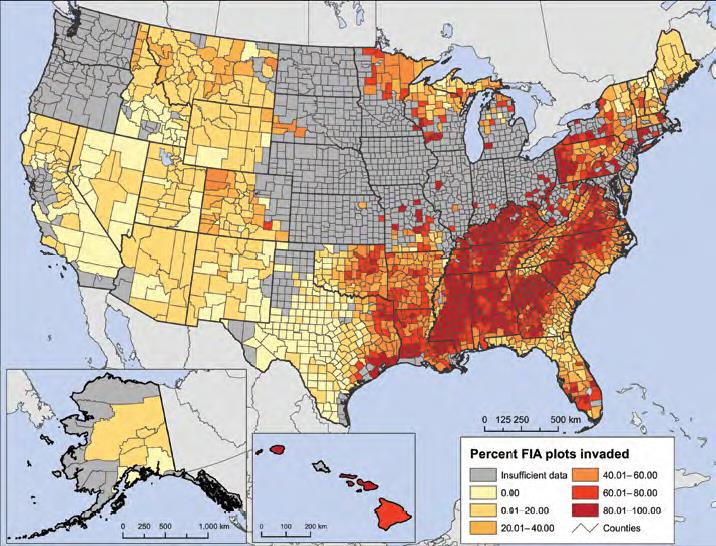

The USFS RPA report gives much more attention to invasive plants than non-native insects and pathogens. The report relies on the findings of Oswalt et al., who based their data on forested plots sampled by the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program. (The RPA also reports on invasive plants detected on rangelands, primarily grasslands.) Oswalt et al. found that 39% of FIA plots nationwide contained at least one plant species that the FIA protocol considers to be invasive and monitors. The highest intensity of plant invasions is in Hawai`i – 70% of the plots are invaded. The second-greatest intensity is in the eastern forests: 46%. However, the map showing which plots were inventoried for invasive plants makes clear how incomplete these data are – a situation I had not realized previously.

I appreciate that the USFS RPA report mentions that propagule pressure is an important factor in plant invasions. This aspect has often been left out in past analyses. I also appreciate the statement that international trade in plants for ornamental horticulture will probably lead to additional introductions in the future. Third, I concur with the report’s conclusions that once forest land is invaded, it is unlikely to become un-invaded. Invasive plant management in forests often results in one non-native species being replaced by another. In sum, the report envisions a future in which plant invasion rates are likely to increase on forest land.

If you wish to learn more about invasive plant presence and impacts, see the discussion of invasive plants in Poland et al., my blogs based on the work by Doug Tallamy, and several other of my blogs compiled under the category “invasive plants” on this website.

I believe all sources expect that the area invaded by non-native plant species, and the intensity of existing invasions, will increase in the future.

The USFS RPA links these invasions to expansion of the “wildland-urban interface” (“WUI”). These areas increased rapidly before 2010. At that time, they occupied 14% of forest land. The report published in 2023 did not assess their future expansion over the period 2020 to 2070. However, it did project increased fragmentation in many regions, especially in the RPA Western and Southeastern regions. Since “fragmentation” is very similar to wildland-urban interfaces, the report seems implicitly to project more widespread plant invasions in the future.

Specifically: Insects and Pathogens

The USFS RPA report on insects and pathogens is brief and contains puzzling errors and gaps. It says that the tree canopy area affected by both native and non-native mortality-causing agents has been consistently large over the three most recent five-year FIA assessment periods. It notes that individual insects or diseases have extirpated entire tree species or genera and fundamentally altered forests across broad regions. Examples cited are chestnut blight and emerald ash borer.

The USFS RPA report warns that pest-related mortality might be underreported in the South, masked by more intense management cycles and higher rates of tree growth and decay. On the other hand, the report asserts that pest-related mortality is probably overrepresented in the Northern Region in the 2002 – 2006 period because surveyors drew polygons to encompass large areas affected by EAB and balsam woolly adelgid (Adelges piceae) infestations. The latter puzzles me; I think it is probably an error, and should have referred to hemlock woolly adegid, A. tsugae. Documented mortality has generally been much more widespread from insects than diseases, e.g., bark beetles, including several native ones, across all regions and over time, especially in the West – where the most significant morality agents are several native beetles. The USFS RPA report mentions that the Northern Region has been particularly affected by non-native pests, including EAB, HWA, BWA, beech bark disease, and oak wilt. It mentions that Hawai`i has also suffered substantial impacts from rapid ʻōhiʻa death.

Defoliating insects have affected relatively consistent area over time. This area usually equaled or exceeded the area affected by the mortality agents. Principal non-native defoliators in the Northern Region have been the spongy moth (Lymantria dispar); larch casebearer (Coleophora laricella); and winter moth (Operophtera brumata). In the South they list the spongy moth.

More disturbing to me is the USFS RPA report’s conclusion that the future impact of forest insects is highly uncertain. The authorsblame the complexity of interactions among changing climate, those changes’ effects on insect and tree species’ distributions, and overall forest health. Also, they name uncertainty about which new non-native species will be introduced to the United States. I appreciate the report’s avoidance of blanket statements regarding the effects of climate change. However, other studies – e.g., Poland et al. – have incorporated these complexities while still offering conclusions about a number of currently established non-native pests. Finally, I am particularly dismayed that the USFS RPA does not provide analysis of any forest pathogens beyond the single mention of a few.

I am confused as to why the USFS RPA report makes no mention of Project CAPTURE (Conservation Assessment and Prioritization of Forest Trees Under Risk of Extirpation). This is a multi-partner effort to prioritize U.S. tree species for conservation actions based on invasive pests’ threats and the trees’ ability to adapt to them. Several USFS units participated, including the Southern Research Station, the Eastern Forest Environmental Threat Assessment Center, and the Forest Health Protection program. The findings were published in 2019. See here. Lead scientist Kevin Potter was one of the authors of the RPA’s chapter on disturbance.

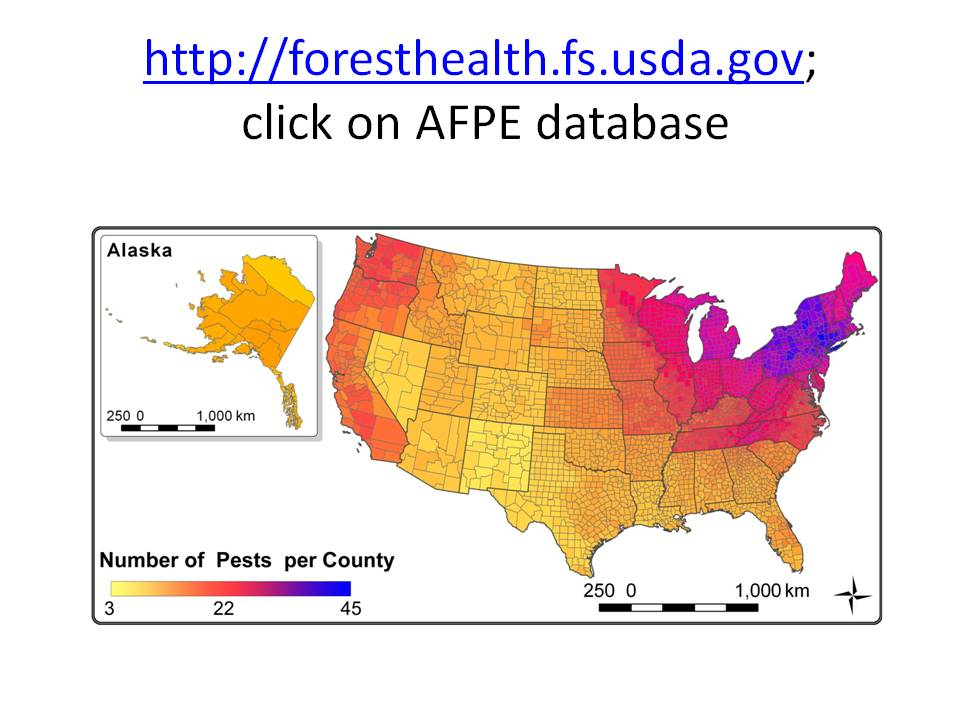

“Project CAPTURE” provided useful summaries of non-native pests’ impacts, including the facts that

- 54% of the tree species on the continent are infested by one or more non-native insect or pathogen;

- nearly 70% of the host/agent combinations involve angiosperm (broadleaf) species, 30% gymnosperms (e.g., conifers). When considering only non-native pests, pests attacking angiosperms had greater average severity.

- Disease impacts are more severe, on average, than insect pests. Wood-borers are more damaging than other types of insect pests.

- Non-native agents have, on average, considerably more severe impacts than native pests.

Project CAPTURE also ranked priority tree species based on the threat from non-native pests (Potter et al., 2019). Tree families at the highest risk to non-native pests are: a) Fagaceae (oaks, tanoaks, chestnuts, beech), b) Sapindaceae (soapberry family; includes maples, Aesculus (buckeye, horsechestnut); c) in some cases, Pinaceae (pines); d) Salicaceae (willows, poplars, aspens); e) Ulmaceae (elms) and f) Oleaceae (includes Fraxinus). I believe this information should have been included in the Resources Planning Act report in order to insure that decision-makers consider these threats in guiding USFS programs.

I also wish the USFS RPA had at least prominently referred readers to Poland et al. Among that study’s key points are:

- Invasive (non-native) insects and diseases can reduce productivity of desired species, interactions at other trophic levels, and watershed hydrology. They also impose enormously high management costs.

- Some non-native pests potentially threaten the survival of entire tree genera, not just individual species, e.g., emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease. I add white pine blister rust and laurel wilt.

- Emerald ash borer and hemlock woolly adelgid are listed as among the most significant threats to forests in the Eastern US.

- White pine blister rust and hemlock woolly adelgid are described as so profoundly affecting ecosystem structure and function as to cause an irreversible change of ecological state.

- Restoration of severely impacted forests requires first, controlling the non-native pest, then identifying and enriching – through selection and breeding – levels of genetic resistance in native populations of the impacted host tree. Programs of varying length and success target five-needle pines killed by Cronartium ribicola; Port-Orford cedar killed by the oomycete Phytophthora lateralis; chestnut blight; Dutch elm disease; butternut canker (causal agent Ophiognomonia clavigignenti juglandacearum), emerald ash borer; and hemlock woolly adelgid.

- Climate change will almost certainly lead to changes in the distribution of invasive species, as their populations respond to increased variability and longer-term changes in temperature, moisture, and biotic interactions. Predicting how particular species will respond is difficult but essential to developing effective prevention, control, and restoration strategies.

Poland et al. summarizes major bioinvaders in several regions. Each region except Hawai`i (!!) includes tree-killing insects or pathogens.

It is easier to understand the RPA report’s not mentioning priority-setting efforts by two other entities, the Morton Arboretum and International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). These studies were published in 2021 and their lead entities were not the Forest Service – although the USFS helped to fund the U.S. portion of the studies.

The Morton Arboretum led in the analysis of U.S. tree species. It published studies evaluating the status of tree species belonging to nine genera, considering all threats. The Morton study ranked as of conservation concern one third of native pine species; 31% of native oak species; significant proportion of species in the Lauraceae. The report on American beech — the only North American species in the genus Fagus – made no mention of beech leaf disease – despite it being a major concern in Ohio – only two states away from the location of the Morton Arboretum near Chicago.

Most of the species listed by the Morton Arboretum are of conservation concern because of their small populations and restricted ranges. The report’s coverage of native pests is inconsistent, spotty, and sometimes focuses on odd examples.

Tree Species’ Regeneration

Too late for consideration by the authors of the USFS RPA report come new studies by Potter and Riitters that evaluate species at risk due to poor regeneration. This effort evaluated 280 forest tree species native to the continental United States – two-thirds of the species evaluated in the Kevin Potter’s earlier analysis of pest impacts.

The results of Potter and Riitters 2023 only partially matched those of the IUCN/Morton studies. The Morton study did not mention three genera with the highest proportions of poorly reproducing species according to Potter and Riitters: Platanus, Nyssa, and Juniperus. Potter, Morton, and the IUCN largely agree on the proportion of Pinus species at risk. Potter et al. 2023 found about 11% of oak species to be reproducing poorly, while Morton designated a third of 91 oak species to be of conservation concern.

I believe Potter and Riitters and the Morton study agree that the Southeast and California are geographic hot spots of tree species at risk.

Potter and Riiters found that several species with wide distributions might be at risk because they are reproducing at inadequate rates. Three of these exhibit poor reproduction across their full range: Populus deltoids (eastern cottonwood), Platanus occidentalis (American sycamore), and ponderosa pine(Pinus ponderosa). Four more species are reported to exhibit poor reproduction rates in all seed zones in which they grow (the difference from the former group is not explained). These are two Juniperus, Pinus pungens, and Quercus lobata. As I point out in my earlier blog, valley oak is also under attack by the Mediterranean oak borer.

SOURCES

Fei, S., R.S. Morin, C.M. Oswalt, and A.M. 2019. Biomass losses resulting from insect and disease invasions in United States forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 116, No. 35. August 27, 2019.

Lugo, A.E., J.E. Smith, K.M. Potter, H. Marcano Vega, and C.M. Kurtz. 2022. The Contribution of Nonnative Tree Species to the Structure and Composition of Forests in the Conterminous United States in Comparison with Tropical Islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. USDA USFS General Technical Report IITF-54

Poland, T.M., T. Patel-Weynand, D.M. Finch, C.F. Miniat, D.C. Hayes, V.M. Lopez, eds. 2021. Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector. Springer Verlag. Available gratis at https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-45367-1

Potter, K.M., M.E. Escanferla, R.M. Jetton, G. Man, and B.S. Crane. 2019. Prioritizing the conservation needs of United States tree species: Evaluating vulnerability to forest insect and disease threats. Global Ecology and Conservation.

Potter, K.M. and Riitters, K. 2023. A National Multi-Scale Assessment of Regeneration Deficit as an Indicator of Potential Risk of Forest Genetic Variation Loss. Forests 2022, 13, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010019

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. 2023. Future of America’s Forests and Rangelands: The Forest Service 2020 Resource Planning Act Assessment. GTR-WO-102 July 2023

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or