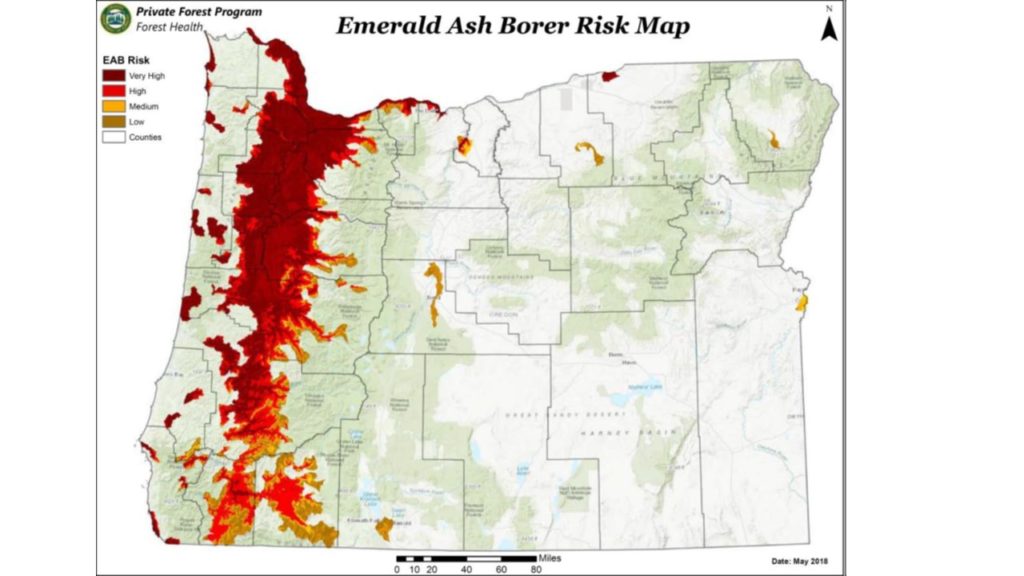

The emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis) is the most damaging forest insect ever introduced. In late June 2022 it was detected in Forest Grove, Oregon — 26 miles from Portland. This is the first confirmation of EAB on the West Coast – a jump of over 1,000 miles from outbreaks in the Plains states. The infested ash trees were immediately cut down and chipped (see Oregon Department of Agriculture website; full link at end of blog). See my earlier blog on EAB’s threat to ash-dominated riparian wetlands in Oregon.

Oregon has been preparing for the EAB:

- The state finalized its response plan in March 2021; see reference at end of blog.

- The state sought and received funds from USDA APHIS to initiate a biocontrol program. The funds were not from APHIS’ operational budget, but from the agency’s Plant Pest and Disease Management and Disaster Prevention Program (PPDMDPP) (Farm Bill money).

- State and federal agencies have begun collecting seeds for resistance screening and a possible breeding program.

EAB: Why Quarantines Are Essential

As you might remember, in January 2021 APHIS dropped its federal regulations aimed at curtailing EAB’s spread via movement of wood and nursery plants. This shifted the responsibility for quarantines to state authorities. Instead, APHIS reallocated its funding to biological control. I raised objections at the time, saying the latter was no substitute for the former.

A new academic study shows that APHIS’ action was a costly mistake.

Hudgins et al. (2022; full citation at end of this blog) estimate EAB damage to street trees alone – not counting other urban trees – in the United States will be roughly $900 million over the next 30 years. These costs cannot be avoided. Cities cannot allow trees killed by EAB to remain standing, threatening to cause injury or damage when they fall.

The authors evaluated various control options for minimizing the number of ash street trees exposed to EAB. They assessed the trees’ exposure in the next 40 years, based on management actions taken in the next 30 years.

In their evaluation of management options, Hudgins et al. tried to account for the fact that the effect of management at any specific site depends on the effects of previous management. Additional complexity comes from the facts that the EAB is spread over long distances largely by human actions (i.e., movement of infested wood); and that biocontrol organisms also disperse.

They conclude that efforts to control spread at the invasion’s leading edge alone – as APHIS’ program did – are less useful than accounting for urban centers’ role in long-distance pest dispersal via human movement. Cities with infested trees are hubs for pest transport along roads. Hudgins et al. say that quarantine programs need to incorporate this factor.

Hudgins et al. concluded that the best management strategy always relied on site-specific quarantines aimed at slowing the EAB spread rate. This optimized strategy, compared to conventional approaches, could potentially save $585 million and protect an additional 1 million street trees over the next 40 years. They also found that budgets should be allocated as follows: 74-89% of funds going to quarantine, the remaining 11% to 26% to biocontrol.

In other words, a coherent harmonized quarantine program – either through reinstatement of the federal quarantine or coordination of state quarantines — could save American cities up to $1 billion and protect 1 million trees over several decades. Since street trees make up only a small fraction of all urban trees, up to 100 million urban ash trees could be protected, leading to even greater cost savings.

Unfortunately, such a coordinated approach seems unlikely. States continue to have very different attitudes about the risk. For example, Washington has no plans to adopt EAB regulations, despite it being detected in Oregon. To the north, Canada already has EAB quarantines and Hudgins et al. advise that they be maintained.

The authors recognize that quarantines’ efficacy is a matter of debate. Quarantines require high degrees of compliance from all economic agents in the quarantine area. Also they need significant enforcement effort. Some argue that meeting either requirement, let alone both, is unrealistic. However, under Hudgins et al.’s model, use of quarantines was always part of the optimal management method across a variety of quarantine efficiency scenarios. Again, these models point to allocating about 75% of the total budget to quarantine implementation. In all scenarios, reliance solely on biocontrol led to huge losses of trees compared to a combined strategy.

Hudgins et al. asked their model for optimal application of both quarantines and biocontrol agents. For example, quarantine enforcement could focus on limiting entry of EAB at sites that: 1) have many ash street trees, 2) currently have low EAB propagule pressure, but 3) are vulnerable to receiving high propagule influx from many sites. Seattle is a prime example of such a vulnerable city with many transportation links to distant cities with significant ash populations.

On the other hand, quarantine enforcement could strive to limit outward spread (emigration) of EAB from which high numbers of pests could be transported to multiple other locales, each with many street trees and low propagule pressure. These sites would be along the leading edge of the invasion and where the probability of long-distance pest dispersal is high.

Authorities should be prepared to adjust quarantine actions in response to changing rates and patterns of invasion spread.

Biocontrol agents should be deployed to sites with sufficient EAB density to support the parasitoids, especially sites predicted to be hubs of spread.

Hudgins et al. concede that they did not explicitly account for:

1) The impact of uncertainty regarding EAB spread on the model;

2) Alternative objectives that might point to other approaches, e.g., minimizing extent of invaded range, or reducing the number of urban and forest trees exposed to EAB;

3) Impacts of predators, such as woodpeckers, on EAB populations;

4) Synergistic impacts from climate change, which by exacerbating stress on ash trees will probably increase tree mortality from EAB infestations; and

5) Variation in management efficiency depending on communities’ capacities.

In the future, Hudgins et al. hope to test their model on other species to determine whether there is a predictable spatial pattern for all wood boring pests, that is, should quarantines always be focused on centers of high pest densities as probable sources of spread. Determining any patterns would greatly assist risk assessment and proactive planning.

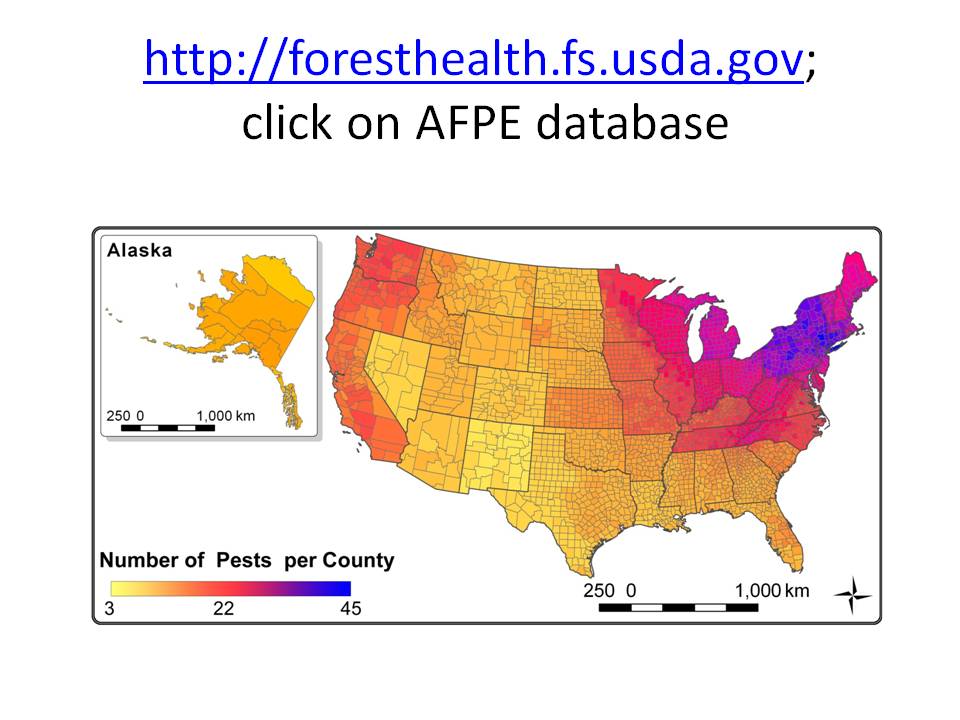

In an earlier study, Dr. Hudgins and other colleagues projected that by 2050, 1.4 million street trees in urban areas and communities of the United States will be killed by introduced insect pests – primarily EAB. This represents 2.1- 2.5% of all urban street trees. Nearly all of this mortality will occur in a quarter of the 30,000 communities evaluated. They predict that 6,747 communities not yet affected by the EAB will suffer the highest losses between now and 2060. However, they evaluated risks more broadly: the potential pest threat to 48 tree genera. Their model indicated that if a new woodboring insect pest is introduced, and that pest attacks maples or oaks, it could kill 6.1 million trees and cost American cities $4.9 billion over 30 years. The risk would be highest if this pest were introduced via a port in the South. I have blogged often about the rising rate of shipments coming directly from Asia to the American South

SOURCES

Hudgins, E.J., J.O. Hanson, C.J.K. MacQuarrie, D. Yemshanov, C.M. Baker, I. Chadès, M. Holden, E. McDonald-Madden, J.R. Bennett. 2022. Optimal emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) control across the U.S. preprint available here: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1998687/v2

Hudgins, E.J., F.H. Koch, M.J. Ambrose, B. Leung. 2022. Hotspots of pest-induced US urban tree death, 2020–2050. Journal of Applied Ecology

Members of this team published an article earlier that evaluated the threat from introduced woodborers as a group to U.S. urban areas; see E.J. Hudgins, F.H. Koch, M.J. Ambrose, B. Leung. 2022. Hotspots of pest-induced US urban tree death, 2020–2050. Journal of Applied Ecology

Oregon Department of Agriculture: https://www.oregon.gov/oda/programs/IPPM/SurveyTreatment/Pages/EmeraldAshBorer.aspx

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or