Two USFS experts have published a chapter describing the components needed to succeessfully breed trees resistant to threatening pests. [See full citation at end of blog.]

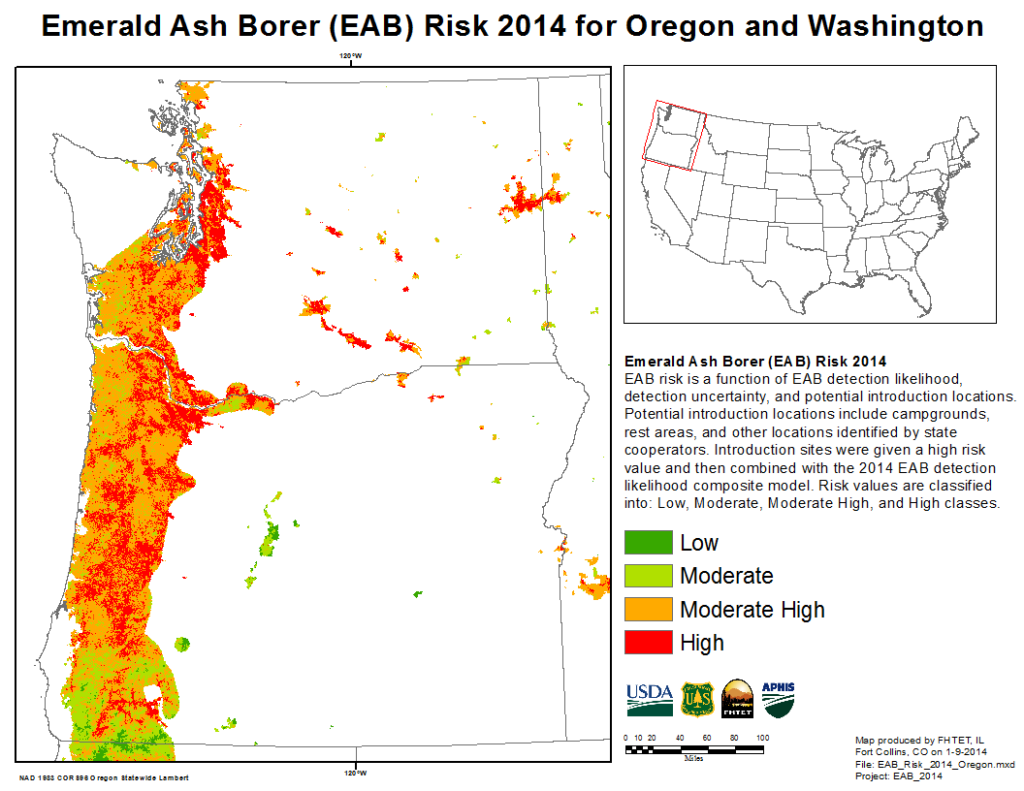

As Sniezko and Nelson note, the threat from non-native pests and pathogens to forest health and associated economic and ecological benefits is widespread and increasing. Further, once such a pest becomes well-established – as some 400 pest species now are — few strategies to save affected species exist except a program to enhance the species’ pest resistance.

From a technical point of view, Sneizko and Nelson find reason for hope. Most tree species have some genetic variation on which scientists can build. It is likely that a well-designed and well-focused breeding program can identify parent trees with some pest resistance; select the most promising; and breed progeny from those parents with sufficient resistance to restore a species.

Furthermore, they say, progress can be made fairly quickly. Scientists can focus on developing genetically resistant populations while postponing studies aimed at understanding details of the mechanisms and inheritance of the obtained resistance.

Fifty years of breeding have revealed the techniques and strategies that work best. As a result, application of classical tree improvement procedures can lead to development of pest-resistant populations within a decade or so in some cases, several decades in others. The time needed depends on the specifics of the pest-host relationship, level of resistance required – and resources available.

In addition, advances in biotechnology can accelerate development of resistance. Tools include improved clonal propagation, marker-assisted selection, and genetic engineering to add resistance gene(s) not present in the tree species.

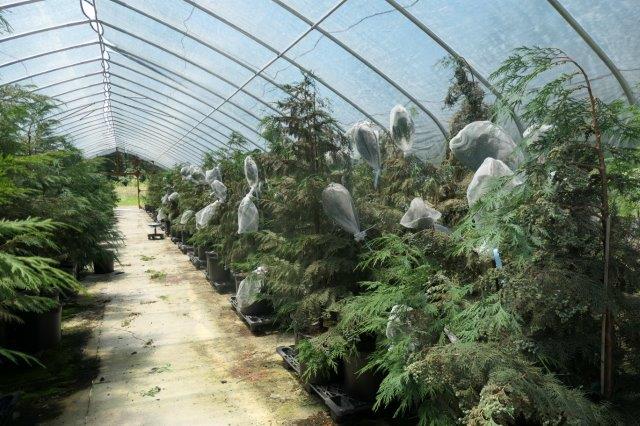

Sniezko and Nelson identify basic facilities needed to support successful breeding programs:

(a) growing space (e.g., greenhouses);

(b) seed handling and cold storage capacity;

(c) inoculation infrastructure;

(d) field sites for testing;

(e) database capability for collecting, maintaining, and analyzing data;

(f) areas for seed orchard development;

(g) skilled personnel (tree breeders, data managers, technicians, administrative support personnel, and access to expertise in pathology and entomology).

Absolutely essential is continuity of higher-ups’ and public’s support.

Sniezko and Nelson note that a resistance breeding program differs from other research projects in its objectives, magnitude and focus. It is an action-oriented effort that is solution-minded—countering the impact of a major disturbance caused by a pest (in our case, a non-native pest).

See the article for more detailed descriptions of each step in the process.

There are two basic stages:

Phase 1:exploration to assess whether sufficient genetic variation in resistance exists in the species. This involves locating candidate resistant trees, preferably across the affected geographic range impacted by the pest; developing and applying short-term assay(s) to screen hundreds or thousands of candidate trees; and determine the levels of resistance present. In addition to those objectives Phase 1 also begins to evaluate the durability and stability of resistance. It is vital to inform stakeholders of progress and engage them in deciding whether and how to proceed.

Phase 2: develop resistant planting stock for use in restoration. This stage relies on tree improvement practices developed over a century, and applies the knowledge gained in Phase 1. Steps include scaling up the screening protocol; selecting the resistant candidates or progeny to be used; establishing seed orchards or other methods to deliver large numbers of resistant stock for planting; and additional field trials to further validate and delineate resistance.

The authors argue that, at present U.S. forestry programs lack a coordinated, focused resistance breeding program based on the components described above. The Dorena Genetic Resource Center (DGRC) – established in 1966 in Oregon and supported primarily by the USDA Forest Service’s regional State and Private Forestry program and National Forest System — fits the bill. The DGRC has sufficient facilities and resources to screen simultaneously tens of thousands of seedlings from thousands of parent trees belonging to several species. Its staff have built up invaluable experience.

However, the Center is regional in scope and focus. (Staff are pleased to offer advice to colleagues working in other parts of the country.) Who will ensure that we make progress on restoring the dozens of tree species in the East under threat from invasive pests? The ashes, hemlocks, elms, beeches, oaks, Fraser fir, dogwoods, redbay and swamp bays, sassafras all need help (Profiles of these trees’ pest challenges can be found at here. [Chestnut and possibly the chinkapins have the benefit of a well-established charity …]

Three case studies illustrate how the process has worked for three groups of species: 1) five-needle pines (subgenus Strobus); 2) Port-Orford cedar (Chamecyparis lawsonii); 3) resistance to fusiform rust (Cronartium quercuum f. sp. fusiforme – a native pathogen) in southern pines.

New Possibilities

Resistance breeding programs are simplest to undertake when tree improvement facilities and experienced staff are already in place. It is most unfortunate that their number has declined significantly. However, a Congressional mandate to pursue resistance breeding as a strategy can partially retrieve and add needed resources.

Some members of Congress have taken steps to partially restore resistance breeding programs. H.R. 1389, cosponsored by Reps. Welch (D-VT), Kuster and Pappas (both D-NH), Stefanik (R-NY), Fitzpatrick (R-PA), Thompson, (D-CA), Ross (D-NC) Pingree (D-ME). Then-Rep. Antonio Delgado also co-sponsored, before resigning to become Lieutenant Governor of New York.

The bill would establish separate grant programs to fund work under the two phases outlined by Sniezko and Nelson. It relies on grants rather than setting up Dorena-like facilities in other parts of the country. Scientists are already setting up consortia to provide the needed facilities and long-term stability e.g., Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Collaborative. Will that be enough?

The most likely way to create a national tree resistance program is to incorporate these ideas into the next Farm Bill – due to be adopted next year (2023).

You can help by contacting members of the House and Senate Agriculture committees and urging them to include in the bill either H.R. 1389 or a more comprehensive program that does establish centers analogous to Dorena.

Also convey your support to USDA leadership – especially the Forest Service and Agriculture Research Service. (APHIS should be part of the team, but its focus is on strategies with more immediate effect.)

As Sniezko and Nelson state, a key component for success is a core group of stakeholders who

- realize the problem (threat to a tree species’ role in the environment);

- acknowledge that resistance breeding offers the best avenue for maintaining the species of concern; and

- express a willingness to invest in a solution that could take one or more decades.

Will YOU be part of this team?

I note that Bonello et al., 2020 (citation below) suggested a new structure to provide the needed focus and coordination. Adoption of H.R. 1389 would partially realize this. The bill calls for a study to examine the benefits of establishing a more secure foundation within USDA for addressing tree-killing pests.

Scott Schlarbaum made similar points in Chapter 6 of Fading Forests III, published in 2014. See links below.

SOURCES

Bonello, P., F.T. Campbell, D. Cipollini, A.O. Conrad, C. Farinas, K.J.K. Gandhi, F.P. Hain, D. Parry, D.N. Showalter, C. Villari, K.F. Wallin. 2020. Invasive tree Pests Devastate Ecosystems – A Proposed New Response Framework. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. January 2020. Volume 3. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2020.00002/full

Sniezko, R.A. and C.D. Nelson. 2022. Chapter 10, Resistance breeding against tree pathogens. In Asiegbu and Kovalchuk, editors. Forest Microbiology Volume 2: Forest Tree Health; 1st Edition. Elsevier

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or